Locals Push Back Over Red Hook Rezoning That Seeks to Bypass Public Review

A proposed 15-story mixed-use development on polluted land in a protected industrial area is facing blowback from locals who accuse the builders of bypassing public scrutiny by applying for an obscure city zoning variance to push through the contentious project.

Rendering via Arquitectonica

A 15-story mixed-use development slated to bring 210 apartments to Red Hook is facing blowback from area Council Member Carlos Menchaca and local residents, who accused the builders of bypassing public scrutiny by applying for an obscure city zoning variance to push through the contentious project.

Former City Planning exec and Red Hook designer Alex Washburn pitched the proposal at 145 Wolcott Street as a “Model Block” — featuring housing, manufacturing, retail and artist spaces that would replace the last-mile delivery warehouses popping up in waterfront neighborhood.

Menchaca, however, scolded Washburn and his development partner Four Points for applying with the city’s five-member Board of Standards and Appeals, rather than asking for a rezoning through the lengthy Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP — which would provide more opportunity for public input, and allow the City Council to reject the development.

“Going through the BSA deliberately circumvents participation and oversight — there’s just no way around that,” Menchaca said at Community Board 6’s virtual Landmarks and Land Use Committee meeting on Thursday. “ULURP is flawed, yes, and it should be replaced, but at least it requires community participation and community oversight through each step of that process.”

The 172-foot-tall development is slated to include 210 new apartments across 169,403 square feet of residential space, 61 of which will be earmarked as “affordable” based on residents’ incomes, while 141 will be market rate, along with eight artist residences.

Ten of the apartments will be aimed at lower-income residents making 40 percent of Area Median Income, or $40,960 for a family of three. Ten more units will be restricted to those making 60 percent of AMI, or $61,440 for a family of three. The rest of the income-restricted units — 41 apartments — will be geared to occupants making 130 percent AMI, which equates to a salary of $133,120 for a family of three.

The 20 units priced at 40 and 60 percent AMI would be a genuinely good deal with rents starting at $567 for a studio and going up to $1,570 for a three-bedroom, according to a financial report the developers submitted with the application.

However, the majority of “affordable” apartments at 130 percent AMI are in line with or even above existing local rents, the report said, with renters having to shell out $2,155 for a studio, $2,700 for a one-bedroom, and $3,235 for a two-bedroom apartment. Local rents average $2,170 per month for a studio, $2,667 for a one-bedroom, and $3,146 for a two-bedroom, according to the report.

These income-restricted units will bring in almost $12.2 million in tax benefits for the developer under New York’s voluntary 421-a tax break program, according to the financial report — and the developers have promised that the apartments will stay rent stabilized for 35 years, as long as the tax incentives last.

The development will also include 65,675 square feet of light manufacturing space and 74,325 of commercial space for restaurants, shops, maker spaces and creative office spaces, with a goal of bringing more than 337 jobs to the venue, according to the builders.

Menchaca, who recently used his sway over ULURPs to help shoot down a planned expansion of the Industry City complex, claimed that the developer had approached his office some years ago, intending the project to go through the normal channels — and questioned why they instead turned to the BSA, stripping him of a chance to demand changes to the plan in exchange for his vote of approval.

The legislator — who is vying to be the city’s next mayor — noted that unlike ULURP, the BSA application also does not guarantee any affordable housing, and involves a less rigorous environmental review.

“Proposing a project on this scale in one of the most flood-prone neighborhoods in New York City should be subject to a much more rigorous and transparent environmental review by the community,” he said. “It is in fact a blank check to build housing, period… Why should the community trust the applicant on their word alone?”

ULURP guarantees numerous points of public input, including advisory recommendations from the local community board and the borough president, along with binding votes from the City Planning Commission and the City Council. As well, rezonings that go through the ULURP process typically require a greater number of units aimed at lower-income residents than the 421-a program, reducing potential profits for the developer.

Council lawmakers usually side with the local council member on land use issues following an unwritten rule known as “member deference,” giving politicians like Menchaca significant bargaining power in exchange for their support.

In contrast, BSA grants exceptions, or “relief,” from the city’s zoning code if the applicant can prove that the current restrictions impose a unique hardship — such as an oddly shaped lot or a bridge that blocks development space above — which prevents developers from making enough money to pay for a project.

The board can approve a variance if applicants meet conditions, which include proving they suffer a unique hardship; that the hardship is not self imposed; that the development won’t change the “essential character” of the neighborhood; and that their request is the least amount of zoning change needed allowing the owners to make a “reasonable return” on the project.

No other votes are required from the Council or the CPC for approval, but the community board can submit non-binding recommendations and the general public can submit testimony.

Washburn — who previously worked as the city’s chief urban designer during the Michael Bloomberg administration — explained that he opted for BSA after fellow bureaucrats advised him the city would not grant a residential rezoning for the lot, because it sits in the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Business Area, a zone specifically set aside for manufacturing wrapping around the shorelines of Red Hook, Gowanus and Sunset Park.

“There’s a policy to protect the [Industrial Business Zone] that won’t allow [the city] to consider a ULURP with residential in it,” Washburn said, relating his conversations with city planners.

The developers and a cadre of their lawyers and consultants argued that the project qualified for the exemption because of historic industrial pollution and unstable landfill beneath the site.

Environmental investigators for the developers found contamination up to 90 feet deep, including toxins like the chemical compound polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), arsenic, lead, petroleum and tar, according to Michael Burke, a principal for the consultancy Langan Engineering and Environmental Services, which prepared a report for the builders.

The developer team has enrolled in the state’s Brownfield Cleanup Program and is working on a plan to remediate the site, which must be approved by the state’s departments of Environmental Conservation and Health before they can start scooping out the toxic muck.

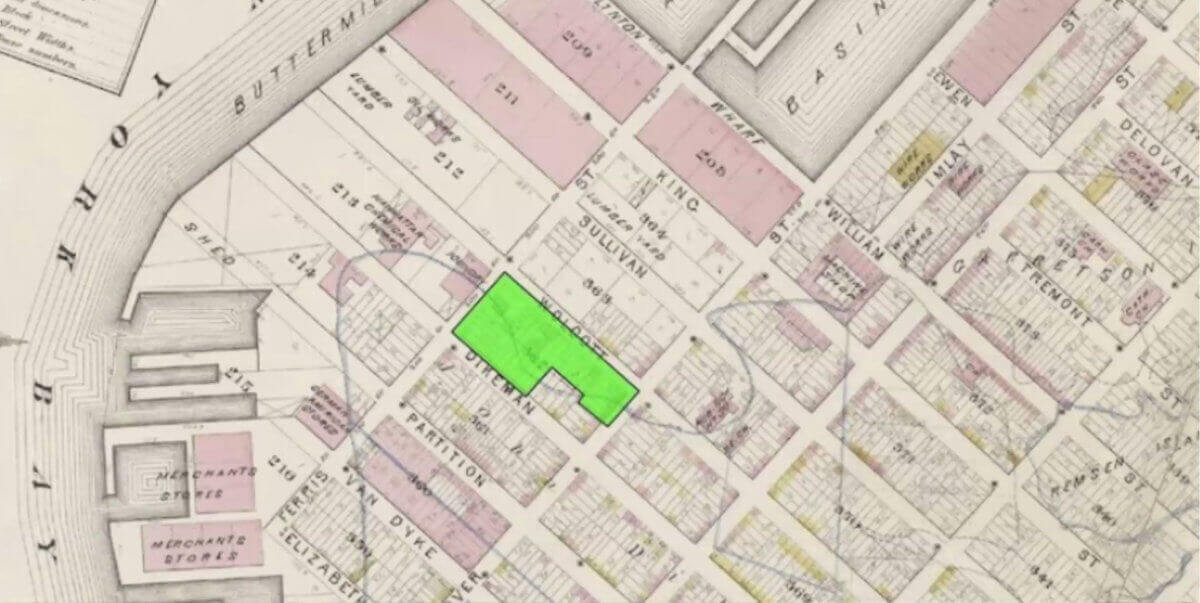

Some of the ground below is landfill along Red Hook’s old shoreline, which snakes beneath the property and leads to unstable soils that make site development more difficult, according to Washburn.

“We have a combination of pollution and, to make it even more tricky, a shoreline… it was filled in in the 19th century,” he said. “Our block is exactly the line that is half water and half land and you have stable and unstable soils with an area that needs a large amount of remediation.”

A lawyer for the developers argued that they needed to bring in more revenue from residential units to pay for the steep up-front costs of cleaning up the site, something he said would not be feasible with an as-of-right manufacturing building.

“The costs are going to be there either way,” said John Beene. “If the same costs are going to be incurred, if you’re taking a huge loss before you even start to develop, then that puts you in the realm of being eligible for a variance.”

The CB6 committee and members of the public discussed the project for the better part of two hours, but the civic panel eventually decided to recommend rejecting the proposal, saying the developer could make enough money to qualify for a variance without building residential.

“This is not the least that they could do. The least would be a smaller building or stay within the manufacturing zoning district and look for a larger building that way,” said board member Jerry Armer.

Armer added that the building’s 15-story height was out of place with the low-slung neighborhood immediately surrounding it — although the developers pointed to a 14-story public housing project a few blocks away — and said that allowing apartments would set a precedent for more residential development in the IBZ.

“This proposal will open the door for additional variances within the IBZ and will destroy what the IBZ is designed to do,” he said.

The committee voted unanimously with 12 votes to recommend rejecting the approval. Their vote will come to the full board for a vote at CB6’s March 10 general meeting, before they send their recommendation to the BSA.

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- City Planner Turned Developer Seeks Variance to Put Up 15-Story ‘Model Block’ in Red Hook

- Local Pols Call on United Parcel Service to Halt Demolition of Historic Red Hook Warehouse

- Chetrit Plans ‘State-of-the-Art’ Warehouse to Replace Red Hook’s Historic Bowne Storehouse

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment