What Is ULURP? And Why Do We Have It?

Name some of the city’s biggest or most controversial development projects — Hudson Yards, Rheingold, Brooklyn Heights library, Pier 6, Hunter’s Point — and chances are good they have gone, are going, or will go through ULURP. But what is it? And why? ULURP Stands for Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. It’s a seven-month process that lets a…

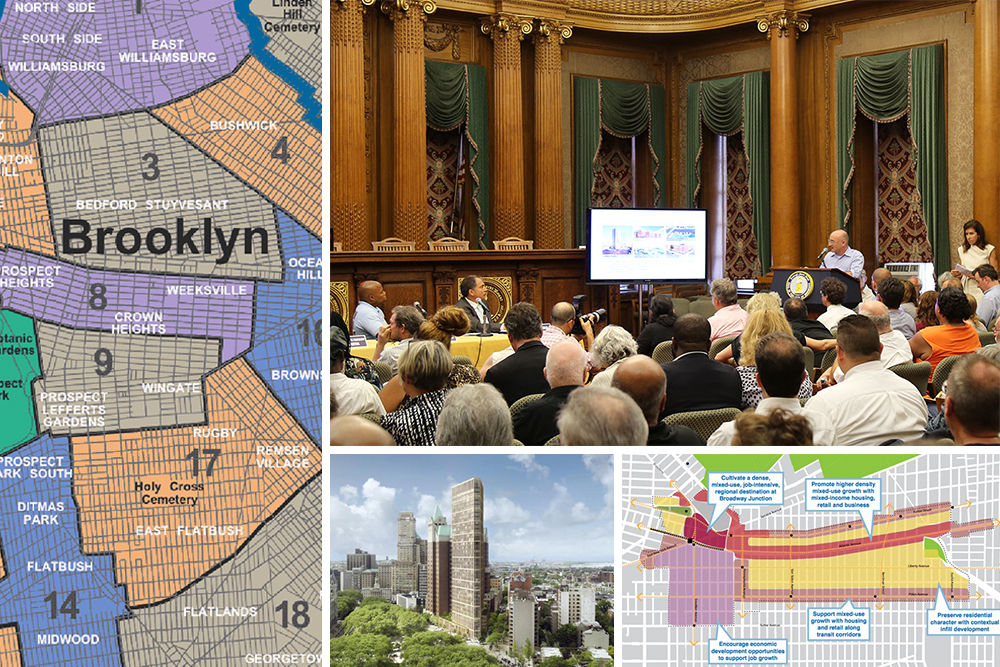

Name some of the city’s biggest or most controversial development projects — Hudson Yards, Rheingold, Brooklyn Heights library, Pier 6, Hunter’s Point — and chances are good they have gone, are going, or will go through ULURP.

But what is it? And why?

ULURP Stands for Uniform Land Use Review Procedure.

It’s a seven-month process that lets a lot of different people decide if the city should allow an exception or change how we’re allowed to use land within the city boundaries.

You see, just owning property doesn’t mean you can do anything you want with it. If that was true, we could have a very different-looking city — fewer historic buildings, towers of any height, and no rules about what kind of homes or businesses can be where.

Instead, we have zoning that protects industrial areas and caps the height of buildings, and we have landmarked districts that can’t change too much.

Want to Buck the Rules? You Have to Go Through ULURP.

A proposal only needs to go through ULURP if it requires a zoning change. It could mean making an exception to the existing rules for a specific property, a neighborhood — or changing the zoning rules entirely.

Want to build a normal-looking house in a residential neighborhood? You don’t need ULURP.

Want to build a giant condo tower that’s higher and denser than currently allowed? ULURP! Want to change the zoning of a lot from manufacturing to residential? ULURP!

Controversy Isn’t Technically a ULURP Requirement.

Because you initiate the process only when you want to change land use rules — to build taller, denser or with a different use than allowed — a number of projects going through ULURP tend to be controversial.

On the other hand, many controversial projects don’t need ULURP approval because they play by existing rules. The 23-story 626 Flatbush Avenue in PLG or even the as-of-right option for redeveloping LICH are just two examples of developments that don’t require land use changes, and didn’t or won’t go through ULURP.

ULURP Was Created to Prevent Robert Moses-Like Mega-Projects.

From 1922 through 1968, Robert Moses utterly transformed New York City with sweeping infrastructure projects. As a government employee (most notably as NYC Parks Commissioner, though at one point Moses held 12 positions simultaneously, according to his New York Times obit) Moses had the power to make and destroy neighborhoods.

His efforts displaced more than 250,000 city residents — all in the service of creating 416 miles of parkways, 13 bridges, the BQE and more. Did the community have a say in these projects? Nope. Were they happy with this arrangement? Fuggedaboutit.

As community outcry over Moses’ methods grew, the city looked for a way to inject community input and approval into the zoning and development process.

ULURP was established in 1975 to give community boards a seat at the table and a say in local zoning changes and exceptions. It’s undergone a few amendments in the intervening decades, and today, ULURP involves much more than community board approval.

ULURP Has Six Stages.

Once an application is certified by the Department of City Planning, the project has seven months to move through the next five stages.

1. Department of City Planning Receives and Checks Application.

The DCP makes sure the ULURP application includes all of the information it needs to move forward, including a Draft Environmental Impact Statement detailing how the project would affect its surrounding area. These application materials are key source of information in the decision-making process.

2. Community Board Review and Approval.

Community Boards are the most local form of government in New York City, serving as advisory groups to the Borough President, City Planning Commission and City Council.

After a ULURP application is approved, the local community board has two months to hold a public hearing about the project and make an official recommendation. If they don’t do anything, the application moves to the next stage.

3. Borough President Review and Approval.

After the Community Board has made its recommendation, the borough president has a month to submit his or her own recommendation to the City Planning Commission. A public hearing is not required at this stage, but the borough president might choose to have one — as Eric Adams did for his review of the Brooklyn Heights Library redevelopment proposal.

4. City Planning Commission Review and Approval.

Once the borough president has made a recommendation, the City Planning Commission has two months to hold another public hearing and make their decision. They have three options: approve the plan, approve it with modifications or disapprove it.

In order to pass any of the recommendations, there needs to be a consensus between at least seven commissioners — unless the borough president recommended disapproving the plan, in which case, the vote requires nine commissioners to agree.

If the CPC disapproves a plan at this stage, it’s game over for the project (unless it’s an urban renewal plan, which can still be reviewed by the City Council). If approved, it moves to the next stage.

5. City Council Review and Approval.

Not every approved ULURP application gets reviewed by the City Council. Some circumstances make review mandatory. But if an application was disapproved by the Community Board or borough president, or if the City Council just wants to have a say, they have 50 days to hold a public hearing and make a decision.

Again, they have three options: to approve, approve with modifications or disapprove the decision of the City Planning Commission. It requires a majority vote.

If they want to approve the plan with modifications, they sling their ideas over to the City Planning Commission — which has 15 days to decide if the requested modifications require another environmental review. If so, the Council can’t adopt this position.

6. Mayor Review.

The mayor actually doesn’t need to approve a ULURP application. But following the City Council’s decision, the mayor has a five-day window in which to veto. But the City Council can override the mayor’s decision with a 2/3 vote.

Related Stories

City Council’s Top 5 Concerns About the Brooklyn Heights Library Sale and Development

Brad Lander Comes Out Against Cobble Hill Rezoning for LICH Development

Public Review of Mayor’s Zoning for Affordable Housing Plan Starts September 21

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment