Walkabout: The Tunnel That Ate Brooklyn, Part 1

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story. At one point, in the mid-18th century, Philip Livingston owned most of Brooklyn Heights. His forty-acre farm once spread across the width of the cliffs overlooking the East River. While the town of Brooklyn was growing quickly below and to the north of him, the Heights…

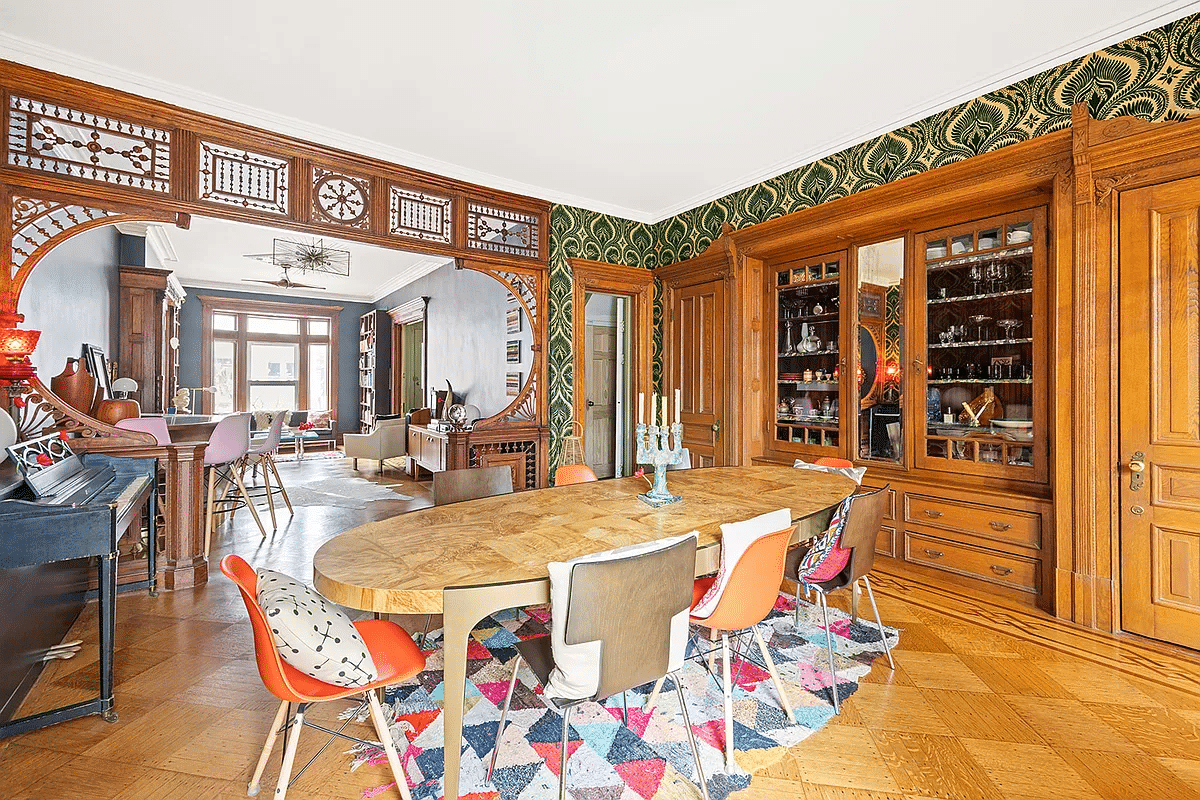

Photograph: Joralemon Street looking towards Hicks, 1905. Photo via Brooklyn Public Library

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story.

At one point, in the mid-18th century, Philip Livingston owned most of Brooklyn Heights. His forty-acre farm once spread across the width of the cliffs overlooking the East River. While the town of Brooklyn was growing quickly below and to the north of him, the Heights were still pasture and farmland, and Livingston’s estate sat on the best part of it. By the time the American Revolution rolled around, Livingston was one of the wealthiest and most influential of Brooklyn’s elite. He was a friend of the patriot cause, and the only signer of the Declaration of Independence from Brooklyn. The Battle of Brooklyn in 1776 was the first major test of that new independence, and was almost the end of everything.

As the British were moving in on a retreating George Washington, the commander of the Continental Army met at Livingston’s manor to plan the retreat across the river to safety in New Jersey. Washington stood on the cliffs of the Heights, looking over at Manhattan wondering if he’d ever see that sight again. Fortunately, he escaped, and after a long and difficult war, American independence was won. But it came with a price. Hard on Washington’s heels, Livingston and his family left Brooklyn, and fled to Kingston and then Poughkeepsie, where family members still live. During the occupation of Brooklyn, the British turned the estate into a brewery and hospital.

After the war, Livingston began selling off parcels of the estate. One of the many familiar names to buy a sizable piece of it was a harness and saddlemaker named Teunis Joralemon, who hailed from New Jersey, by way of Flatbush. In 1803, he purchased a good sized plot, and proceeded to become one of Brooklyn’s most powerful landowners and important citizens.

Brooklyn was growing, and the land on the Heights was too valuable to remain farmland much longer. The city fathers began laying out the street grid, and cutting the old estates into developable plots. Joralemon really didn’t like it, and complained bitterly at town meetings. He especially didn’t like some of the people for whom the streets were being named, DeWitt Clinton, chief among them. But progress is progress, and even Teunis Joralemon realized his land was worth much more developed, than as farmland. Besides, they named an important street after him. Little by little, he sold off his land, and many fine houses were built along the path of the street that bears his name. Teunis became an elder in the Reformed Church, along with Abraham Remsen, Peter Bergen, Leffert Lefferts and Theodorus Polhemus. He died in 1840.

In 1854, a wealthy merchant named John P. Atkinson bought a double sized plot from the Joralemon estate and built a large mansion on the corner of Joralemon Street and Garden Place. 94 Joralemon was a large 41 foot wide Greek Revival style house with an impressive columned entryway opening onto the street. In a neighborhood of large houses, this was larger than most, especially at the time. Atkinson sold the house in 1863 to Edmund C. Fisher, who sold it to Lucius and Harriet Starr in 1866. In 1890, the house was sold by Harriet Starr’s estate to Wilhelmus Mynderse, and it is here that our story really begins.

Wilhelmus Mynderse was from an old Dutch family whose people settled upstate in Seneca Falls. He was born in 1849, was educated at the Pleasant Valley Military Academy in Sing Sing, and then graduated from Williams College. He came to New York City, worked for the NY Sun, and then entered Columbia Law School, graduating in 1875. He joined the firm of Butler, Stillman & Hubbard, which eventually became Butler, Notman, Joline & Mynderse. He was considered one of the foremost experts on admiralty law, and had clients around the world.

Like many powerful and successful Brooklyn men, Wilhemus Mynderse belonged to all of the best clubs, and was a trustee of the Franklin Trust, Exchange National Bank, and several other financial institutions. He was also on the boards of several charities, Brooklyn Hospital, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and the Long Island Historical Society. He and his wife and daughters were at the top of Brooklyn’s social elite. But all of that meant nothing when Progress came to Brooklyn Heights.

In 1903, the ambitious project to dig a subway tunnel between Manhattan and Brooklyn began under the auspices of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, the first underground subway line in Manhattan. Subway transportation between Brooklyn and Manhattan was necessary, and like the Fulton and Wall Street Ferries that had been transporting commuters for 80 plus years, the thousands of commuters travelling back and forth would be well served by this new mode of transportation. It also made sense to have the tunnel stretch under the East River from the Battery to Brooklyn Heights. Now they just had to figure out how to do it.

After much consideration, it was decided that the Brooklyn end of the tunnel would be cut underneath Joralemon Street, and was originally called the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, later changed to the Joralemon Tunnel. The tunnel would consist of two huge parallel cast iron tubes, with a train running in each direction. The engineering for this project would be impressive, as the sandhogs would have to tunnel underneath the river, and through the cliffs overlooking the Heights. No one really knew what was under there, or how difficult it would be to construct.

As the Brooklyn end of the tunnel progressed, the homeowners of Joralemon Street started to notice cracks in their plaster walls. In the summer of 1903, Wilhemus Mynderse began to notice more and more cracks every day, even in the new extension he had built on the back of his house. One night, the family was awakened to groans and rumblings coming from somewhere, and then stopping. They thought it was the wind. The next morning, they found cracks in every wall in the house, and decorative plaster had fallen to the floor. An inspection outside showed that the house was sinking into the ground, settling as though the foundation had been knocked out from underneath. All of the old houses on Joralemon had been settling slowly over the century, that was expected, but the house had sunk two inches the night before, and the walls were in danger of separating, collapsing the house like cards.

Mynderse quickly called his architect, who called the City Engineer, who called the engineers from the tunnel. They all stood around looking at it, perplexed as to what had happened. It wasn’t just 94 Joralemon, either, houses up and down the block were also “settling” overnight. It was theorized that the block sat on a bed of sand, “quicksand” the papers called it, and the tunnel excavation was causing the sands to shift. Mynderse quickly moved to have the building shored up with timbers, and told reporters that he was going to stay in his house until it collapsed, if it came to that. His wife, children and servants probably weren’t as confident of this course of action.

The winter of 1903 turned into the spring of 1904, and tunnel construction continued. The houses on Joralemon continued to slowly settle, with cracks appearing in everyone’s home, but the Mynderse house was getting the brunt of the damage. The family was still living there, but it was getting worse. Because the house was on the corner, it wasn’t being supported by the surrounding homes, and it was pulling away onto Garden Place. In May of 1904, a huge support system was built on the side of the house to shore it up. The other prominent people on the block were also being affected, as well.

Judge George Abbott lived right next door to 94 Joralemon, and as the house pulled away from his own house, he feared the worse. So did Brooklyn Borough President Littleton, who lived on the corner of Hicks and Joralemon. As the tunnel moved closer to his house, he was worried his corner house would suffer the same fate. The engineers working on the problem admitted that they were not worried about losing the rest of the houses on the block, the settling would stop, and the damage could be repaired, but they thought they might lose the Mynderse house. The stoop had pulled away from the house, and the front wall had separated, as well.

In a report to the city, on June 17, 1904, the Rapid Transit Board said in that the problems with pressure in the tunnel were being relieved by the digging of a shaft on Joralemon Street. This shaft would also be used to dig the rest of the tunnel underneath the street, making it easier to join the construction coming from Manhattan with the Brooklyn construction. Pressure had been a major problem with construction, and had resulted in a blowout that shot a workman up through the mud, 40 feet into the air. The Joralemon Street airshaft would alleviate the pressure, and they hoped would also keep the sand from moving around anymore than it had. It would also provide ventilation when the trains were running. Today, that air shaft is the famous hollow house at 58 Joralemon Street, between Hicks Street and Willow Place.

That same day, the Rapid Transit Board announced that the homeowners were on their own when it came to paying for repairs. They said that the city was not liable for the damage. It was all for the greater good, they said, the cost some must pay for building our great city. Next time we’ll see how that worked out. GMAP

(Photograph: Joralemon Street looking towards Hicks, 1905. Brooklyn Public Library)

I feel a punfest coming on. I admit I would not be Mynderse to the idea.

This was great!

I do recall all of that construction on St. Felix back then. 1990’s not early 20th of course.

I have a couple of favorites. Now that the weather is warming up I think is time to try one of these

new restaurants talked about on these blogs.