Walkabout: The Tunnel That Ate Brooklyn, Part 2

Read Part 1 and Part 3 of this story. The residents of Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights woke to read some of the most horrific news a home owner can ever read, emblazoned in the Brooklyn Eagle on June 17, 1904; “Property Owners Must Make Their Own Repairs. City not liable for damage done by…

1913 postcard touting the new Joralemon St. subway tunnel and corresponding stations

Read Part 1 and Part 3 of this story.

The residents of Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights woke to read some of the most horrific news a home owner can ever read, emblazoned in the Brooklyn Eagle on June 17, 1904; “Property Owners Must Make Their Own Repairs. City not liable for damage done by Joralemon Street Tunnel, so says Transit Board.” They couldn’t believe it. It was like being knocked down, beaten up, and then charged for vagrancy. These were well-to-do, important people. They had never been so abused and outraged in their lives. And all for a subway tunnel.

Our story began last time with the building of the Joralemon Street tunnel, a state of the art twin tube of steel and concrete that would connect Manhattan’s new subway to Brooklyn. The tunnel would run from underneath the Battery in Lower Manhattan, under the East River to Brooklyn Heights. This modern feat of engineering would travel underneath Joralemon Street, and then continue on to a newly constructed subway station at Borough Hall. This was part of the Interborough Rapid Transit Line, running today’s 4 and 5 trains.

The Joralemon Tunnel presented all kinds of challenges for the engineers. They had to dig underneath the East River, a fantastic undertaking in of itself, and then aim upwards into the bedrock of Brooklyn. They also had to pressurize the tunnel to keep water out. But the pressure needed to be released, so a tunnel was dug on Joralemon, enabling workers to approach the dig from both sides. That tunnel access point is still able to be accessed at 58 Joralemon Street.

The Mynderse mansion was a grand brick Greek Revival home on the corner of Joralemon Street and Garden Place, built in 1854. It was the largest house on the block, rivaled in size only by the Daniel Chauncey mansion, which was built much later, in 1890. Wilhelmus Mynderse, a wealthy lawyer, bought the house for his family in 1890. He put an extension on the back, and settled in with his family and his art and book collections.

When the Joralemon Tunnel began to be constructed underneath his street, Mynderse was one of the first to notice cracks in his plaster. Over the summer of 1903, the cracks got worse, and finally, one night, the house shifted on its foundation an entire two inches, cracking every wall in the building, and bringing decorative ceiling plaster crashing to the floor. Something was happening underneath Joralemon Street.

The engineers for the tunnel, along with the city engineers and Mynderse’s own architect, figured that there was a bed of sand running underneath the street. The pressure from digging the tunnel, although far below, was causing that sand to move, thus causing Mynderse’s 94 Joralemon St., as well as many of the other houses on the street, to settle and move. Because it was on the corner, and not supported by buildings on both sides, 94 was shifting the most. Of all of the houses on the block, the engineers feared the Mynderse house might not survive.

As a famed expert on admiralty law, Mynderse was not given to panicked action. He calmly set his architect to work, and quickly had the house shored up with timbers and bracing, especially on the open Garden Place side of the house. The family didn’t abandon ship, either; they stayed in the house the entire period the tunnel was being dug. But Mynderse was a New Yorker, and while he was willing to spend what was necessary to save his house, he was keeping his receipts, because there was no way he was going to be paying for this. The City of New York or the Interborough Rapid Transit Company was going to have to write a nice big check when all of this was over. At least that’s what he and his neighbors thought.

The headlines of the Brooklyn Eagle were a shock. Since he had been damaged the most, Wilhelmus Mynderse was at the forefront of the homeowner’s group seeking recompense. The head of the Rapid Transit Commission issued a statement saying that their engineers admitted that the contractors working on Joralemon Street had not done as good a job as perhaps they could have. They’ve “obtained the ill-will of many of the property owners on that account,” the paper wrote.

But as the newspaper account continued, Commissioner Orr wrote Mr. Mynderse in a letter to say, “I regret to say that the board finds itself unable to comply with your request. The things you complain of are either the necessary result of the city’s great public work of creating at great public expense what is in fact and law a great public highway: or else due to some negligence on the part of the contractor, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company – or its subcontractors. In either case, as we are advised by counsel, the City of New York, for which this board acts, is not legally liable.”

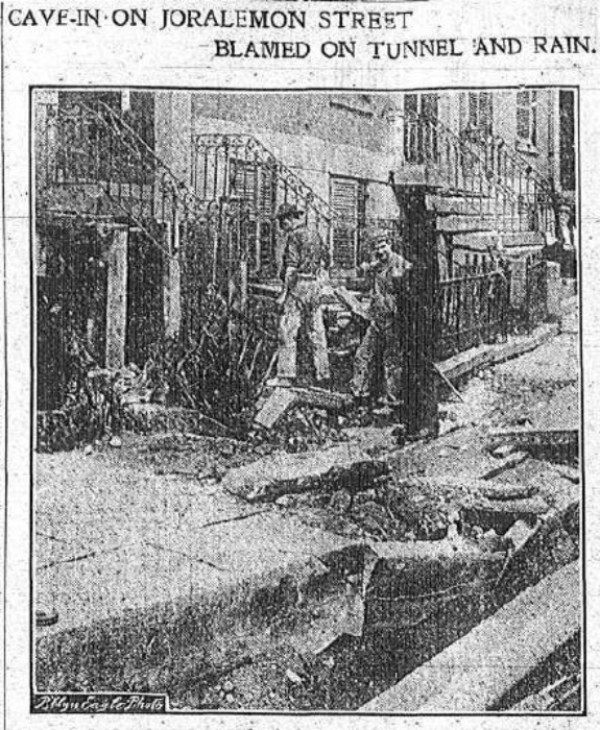

Them’s fightin’ words to any lawyer, and Wilhelmus was one angry lawyer now. He and his neighbors were not going to just accept this. They sued. Meanwhile, the construction continued, and so did the problems. Only a month after the letter from the Commission of the Rapid Transit Board arrived, another accident to property occurred on Joralemon Street. After the tail end of a hurricane passed through Brooklyn, with heavy rains, the entire stoop and sidewalk of 45 Joralemon Street tore away from the house and collapsed. There was also extensive damage to the sidewalk and stoop of 47, next door. A photograph by the Daily Eagle is below.

The contractors of the tunnel denied that their work was the cause of the collapse, and blamed the heavy rains and the storm. Number 45 had a little courtyard to the side of the building. That slipped entirely off its foundations. The paper noted that the stoop of the house looked like it had been cleaved with a knife; it had cleanly separated from the building. Only the mangled railing, which had tried to hold on, and failed, kept the picture from looking like a surgical cut. Workmen shoring up the building and stoop had to put up a ladder so that tenants could get out of the house. The house and its immediate neighbors were all owned by the Packer estate. The damage was repaired, and in the meantime, work continued on the tunnel.

In March of 1905, a miracle of sorts happened in the midst of a disaster. Workmen were installing pressure shields in a portion of the tunnel underneath the river, near the Brooklyn side. One of the shields broke loose and the pressure in the tunnel cause the metal shield to bore through the mud and water to the surface, like a torpedo. The workman closest to the shield was sucked up into the mud and sucked to the surface, as well.

Witnesses said he shot up through the mud and water twenty feet into the air, “performing acrobatics” in the air for a few of the longest seconds in his life, before falling into the water. Miraculously he lived, more amazingly he didn’t have a scratch on him. His fellow workers below were also able to escape through the tunnel to the surface, and only two were seriously injured. This was the first time men had survived a tunnel collapse of this kind. The shield was replaced and the work continued.

In May of 1905, the contracting company hired by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company declared in a city commission meeting that they were not responsible for the damages done to the homeowners of Joralemon Street. The president of the construction company, Andrew Onderdonk, was protesting a proposal in front of the planning board that IRT not be paid until the construction company made good on the damages sustained by the digging of the tunnel, and restored Joralemon Street to the condition it was before the tunnel was begun.

Onderdonk protested, and said that his company had already approached the homeowners, and was in the process of doing repairs, which it estimated would only cost the, ten or fifteen thousand dollars in total. “I didn’t know of the complaints until a few weeks ago,” Onderdonk told the commission. How he missed the shored up houses and collapsed stoops is amazing, but…he went on to say,” As to the damage we have done, I may state that our counsel advised that we were not liable under the law, and neither is the city. On this our counsel was absolutely clear. However, we held a meeting and decided to do our best by the residents.”

Be that as it may, the lawsuit against the city and the IRT proceeded. In 1906, the city bestowed four awards to homeowners affected by the tunnel. These awards were test cases to see how the rest of the plaintiffs in the suit would be awarded damages. There were 400 awards on the line, all property owners, business owners and tenants who demanded satisfaction in the case. Wilhelmus Mynderse received the largest amount; $15,000. The other awards were $6,000 to his next door neighbor, ex-Surrogate Judge George Abbott, and $12,000 to John Notman who owned 136 Joralemon Street. A fourth award of $1.00 to “an unknown property owner” fulfilled some legally arcane clause of the case.

It would not be enough. At the end of the day, several years later, the case was kicked up to a higher court and the city and the IRT were indeed found liable, and paid out several million dollars to various plaintiffs. I could not find an itemized list. The case changed the way the city handled further tunnel building in the future, as well as dealings with the various independent companies that owned the different subway lines. The Mynderse house was repaired, and the rest of the story – the resulting construction scandal, and the further history of the 94 Joralemon Street will conclude next time. GMAP

(1913 postcard touting the new Joralemon St. subway tunnel and corresponding stations)

This is crazy. Great stuff MM. I am sure the people on the U.S are reading this…

This is crazy. Great stuff MM. I am sure the people on the UES are reading this…