Walkabout: The Tunnel That Ate Brooklyn, Part 3

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story. Many people don’t realize that our subway system was once a conglomeration of privately owned subway lines. The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) were the two first lines. The City of New York built the subway tracks, platforms and…

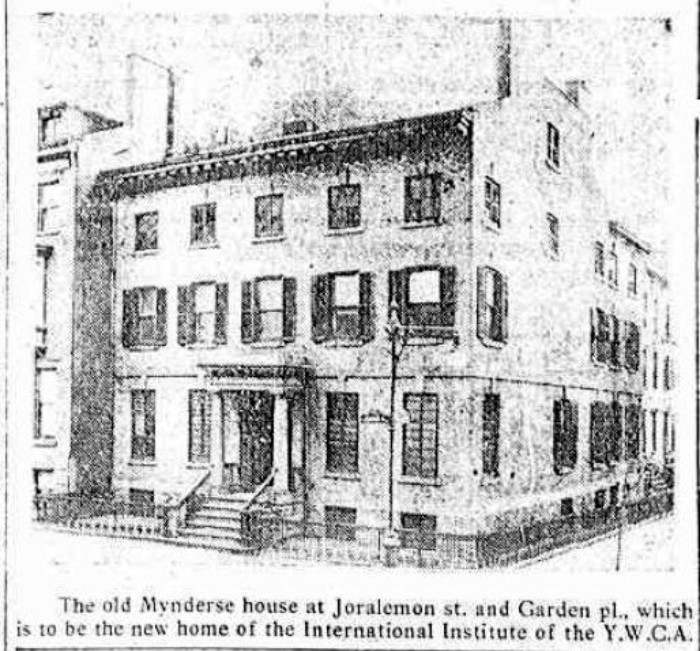

1928 Photograph via Brooklyn Public Library

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story.

Many people don’t realize that our subway system was once a conglomeration of privately owned subway lines. The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) were the two first lines. The City of New York built the subway tracks, platforms and tunnels for these subway trains and leased them to these privately held companies which ran the trains. Both the IRT and BRT trains were the children of the old elevated trains that ran over both Manhattan and Brooklyn. The first underground train began running in Manhattan in 1904.

The idea of a subway was not new, it had been kicking around for years, and probably got its first real wake-up call from the infamous Great Blizzard of 1888, which paralyzed the city under as much as fifty inches of drifted snow. When planners were figuring out where the subway would run, it was a no-brainer that there would be a subway line that traveled under the East River, joining Brooklyn and Manhattan.

As we’ve seen in the last two chapters of our story, the excavation of the first IRT tunnel underneath the river caused all kinds of problems to those above Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights. Buildings shifted on their foundations, sheered-off stoops, cracked walls and downed plaster ceilings told homeowners that they were literally living on shifting sands.

Thousands of dollars of damage was done on Joralemon Street in the years between 1903 and 1905, and initially, the city denied responsibility, refusing to pay homeowners for the damage. But lawsuits were filed with rapidity worthy of today, and eventually, the city and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company were forced to compensate the people of Joralemon Street to the tune of several million dollars.

Nothing teaches a lesson better than losing money, and the city fathers and the subway companies were paying attention. One subway tunnel under the East River was only the beginning. There would be more lines joining Manhattan and the other boroughs, excepting Staten Island. How would those tunnels be built, and would another Joralemon Street be in the offing? Not if they could help it. And because this was, after all, New York, the solutions found themselves mired in political mud. But first, there’s a bit of back story that needs to be told here:

The IRT was owned by Augustus Belmont, Jr., of the Belmont Stakes and thoroughbred racing fame. Belmont already had a monopoly on Manhattan travel, as he also owned the elevated Manhattan Railway. In addition, he owned the Rapid Transit Construction Company, the subway construction arm of his business. In 1900, he outbid Andrew Onderdonk for the rights to build the subway lines in Manhattan.

Over here in Brooklyn, the independent BRT carried 95% of the train traffic in this city, and owned the trolley lines as well. When the plans for the Joralemon Street tunnel were announced, the BRT was poised to bid for the lucrative contract to build the tunnel too. If the BRT could cross the river, it would also have a chance to branch out into Manhattan. The Belmont syndicate did not want Brooklyn on Manhattan tracks, and pulled out its secret weapon: Charles Francis Murphy of Tammany Hall.

Charles Murphy ran Tammany Hall from 1902 to 1924. He succeeded the infamous Richard Croker, the corrupt Tammany head who helped Charles Morse get and keep a monopoly on the ice that came into New York City, among other things. That story was told here. Murphy was just as powerful and corrupt as Croker, but he was much smoother and more respectable about it. August Belmont could work with a man like that, and did. Murphy was able to muster critical community support for Belmont’s IRT, and Belmont, in turn, made sure plenty of Tammany men were employed as workmen on those tunnels.

Murphy had established his own construction company. It was headed by his brother John, who before this had been a liquor salesman, and a local alderman Gaffney, or his wife. The wife was appointed treasurer of the new company, a position that she told the Brooklyn Standard Union that she didn’t know anything about. The company was called the New York Construction and Trucking Company, and through Boss Murphy, was able to obtain any contract it wanted with the city.

They joined with Belmont, and voila! The IRT and Belmont got the contract to build the Joralemon tunnel. The Murphy people were not the builders of the tunnel, but their men worked on subway construction in other projects. Part One and Part Two of our story chronicles the story of the tunnel and its effect on the people of Joralemon Street. The first trained rolled through the tunnel on January 9th, 1908.

Our main player on Joralemon, Wilhelmus Mynderse, died on November 15th, 1906. He had fallen ill with pneumonia, and died of heart failure a week later at his home at 94 Joralemon Street. He was only 57 years old. He was survived by his wife Hannah and his daughter, who was Hannah’s step-daughter. He had been the driving force in fighting the city and the IRT to get them to pay for the damages done to his property and that of his neighbors.

His house, because it stood on an open corner, had sustained much more damage than most, and had to be shored up with tall timbers and a wooden exo-structure in order to prevent it from falling down. Although he had received some compensation for damages, most of the settlement money would not come to his wife until after his death. Hannah Mynderse lived in the house with her servants for another twenty years.

By September of 1925, the subway lines between the boroughs had greatly expanded. The preferred method of digging by that time was the open cut method, where the street was torn up, the ground excavated, the tubes laid, the stations hollowed out, and then the whole thing was covered up again. It was messy and highly disruptive, but effective. There was another construction type, called the shield method, that used a large machine like a giant biscuit cutter to cut a circular tunnel underground.

This hole was larger than the steel tunnel tubes that were placed in it. But because of the way the shield cutter was constructed, it was impossible to get around it. The empty spaces between the tube and the earth couldn’t be filled fast enough, and the earthworks fell, causing foundations to shift, walls to crack and other similar damage to the buildings above the tubes. It was Joralemon Street all over again, across the city. The shield method was costing the construction companies, as well as the city, too much money, so it had been dropped in favor of the open cut. But what about under the rivers and in places where open cut could not work?

By 1925, an enterprising engineer had an answer. Major John Francis O’Rourke, president of the O’Rourke Engineering Construction Company had figured out how to make shield cutting work. O’Rourke, who came to America from Ireland as an infant, had a degree in civil engineering from Cooper Union, and post graduate work in higher mathematics. He became a Major in the National Guards, 13th Regiment. He was a long time railroad man, and was the deputy chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission in 1901, leaving to form his own construction company.

They worked on Grand Central Terminal, the tunnels for the Pennsylvania Railroad, and railroad tunnels in Cleveland that traveled miles under Lake Erie. The man was a genius, and had already revolutionized subway construction by inventing an interconnecting concrete block that bonded seamlessly with its neighbor without cracking, dovetailed together forever with the natural pressure exerted upon it. He first used these blocks in his Cleveland tunnel. He thought he could figure out how to make the shield work.

He would add a component to the shield cutter, similar to a sandblaster, that would shoot gravel and earth backwards as the machine cut, filling the space in as the sections of the tube were laid, eliminating the voids that caused aboveground damages. He tested his machine, and then bid on the project to lay tunnel in Williamsburg. His bid was a million dollars less than his competitor. He won, used his machine, and paved the way for underground tunnel construction thereafter. The remaining subway lines were created with both open cut and shield methods, depending on location and circumstances.

Back at the Mynderse house at the center of the first subway tunnel problems, things were not going well. Hannah Mynderse had remained at 94 Joralemon Street for twenty years after her beloved husband Wilhelmus had died. Her step-daughter was married, living out of state, and she was rattling around in the big house with two paid companions and three other servants. By 1927 she had been blind for seven years, and had sunken into deep depression.

She was under a doctor’s care, but when her regular physician fell ill himself, Hannah came under the care of a different doctor. Perhaps she took this change as her chance. On May 11th, 1927, Mrs. Hannah Mynderse was found dead in her bed, an empty bottle of chloroform liniment by her side. Her companion, a registered nurse, was unable to revive her, and called the doctor. He pronounced her, and a later report by the coroner confirmed it was a suicide. She had left no note. That determination was later changed to a pronouncement of accidental death, caused by her blindness. Suicide was not an acceptable option for the lonely old lady whose family traced back to the Mayflower.

The bulk of her estate went to a niece, with large donations to an Episcopalian Mission house on Remsen Street, and to two college scholarships, all in Wilhelmus Mynderse’s name. A year later, the house at 94 Joralemon Street was sold to the Young Women’s Christian Association, and would become the International Institute of the YWCA. The Institute would be moving there from their present location nearby on Sidney Place. The Mynderse house was twice as big, and would be renovated for their growing needs.

The YWCA planned to keep much of the parlor floor intact, with its grand parlors and library extension. Upstairs, rooms to house at least twenty girls and women were to be created. The International Institute was a safe refuge for young women from other countries traveling to New York, and had many programs to help them settle in a new land. In the ten years of the Institute’s history, they had outgrown three other locations. This time, they stayed.

When Clay Lancaster wrote his groundbreaking study of the pre-Civil War houses of Brooklyn Heights, published as “Old Brooklyn Heights: New York’s First Suburb,” the 1965 edition listed the house as still belonging to the YWCA. Brooklyn Heights became the first historic district under the new Landmarks Preservation law that same year, helped in no small part by Mr. Lancaster’s efforts and meticulous research. In the following years, 94 Joralemon changed hands again, and is now a condominium with five apartments. No trace of the problems that plagued this storied home are visible today, and visitors still marvel at the home’s size and beauty. Thank goodness it has always been a keeper. GMAP

I second this. So interesting. Thanks MM!