Walkabout: Harmony Mills, a Troy-ish Story, 4

Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of this story. Standing on the edge of the mighty Mohawk River in Cohoes, NY, Harmony Mill No. 3 was the largest single cotton factory in the world when it was finished in 1872. Stretching over 1, 100 feet in length, the five story building held enough…

Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of this story.

Standing on the edge of the mighty Mohawk River in Cohoes, NY, Harmony Mill No. 3 was the largest single cotton factory in the world when it was finished in 1872. Stretching over 1, 100 feet in length, the five story building held enough spinning and weaving machinery to produce 700,000 yards of cotton goods a week. Seven hundred THOUSAND yards. And that was just Mill No. 3. The complex had three other mills on site, as well as outbuildings for various other functions.

And then there was the housing. The first worker’s tenements were built next to the river on several streets near the mill. They consisted of three and four story brick row houses in the Greek Revival style. When Mill No. 3 was finished, the need for far more housing was met by the purchase of 70 acres on the hill overlooking the plant, which was re-named Harmony Hill.

By the time they were done building here on the hill, there were 800 tenement houses, five large boarding houses for unmarried workers and a company store. Harmony Hill was a self-contained town of single, double houses, both detached and row houses, as well as shops, churches, and schools. Harmony Mills had its own police force, garbage collection, street paving and repair crews and other maintenance workers. By the beginning of the 20th century, Harmony owned three-quarters of Cohoes, and employed at least one member of every family in the city, in one way or another.

For more information on the history of the mill, and how it worked, please see the links to the previous chapters in this story below. We’ve looked at the physical structure of Harmony Mills, but who made it all work? The owners and management get the glory, but the reason Harmony Mills was so successful was the productivity of all of its workers. Who were they, and what was it like to work here?

Robert Johnston was the English-born manager of Harmony Mills through the period of its most rapid growth and continued success. When the mill began to grow,he went back to England to buy new and better equipment. While he was there, he recruited experienced English and Irish weavers and textile workers to come to America. In the year between 1866 and 1867, over 5,000 operatives and their families set sail to New York to work at Harmony Mills. The company paid for their passage to Cohoes, and when they arrived, the new homes on Harmony Hill were waiting for them.

They joined a large workforce of mostly Irish workers. After Mill No. 3 was completed in 1872, advertisements were sent as far away as French speaking Quebec for more workers. North America was in a recession, and many unemployed French Canadians picked up and moved south to fill the rest of the positions in the plant. The unmarried workers lived in large boarding houses, and the families lived in the houses and tenements, which had four to ten rooms each, and were rented to employees for three to eight dollars a month.

Harmony Mills’ housing stock was far superior to anything else in town, where rooms in rickety wood-framed tenements on dirty streets could cost twenty dollars a month. Here at Harmony, one could live in a well-built brick home with modern conveniences, a home that had a small lawn and a garden, on paved and cared-for streets. The rent was deducted from the workers’ salaries. Families could save, and even take in boarders, if they had extra room. Company housing provided upward mobility, and the chance of home ownership, a very important cultural goal for all of the immigrants.

That’s not to say Harmony didn’t make them work for the privilege. Everyone at the mills worked long, hard hours, and the pay was typical 19th century mill and factory pay. In other words, it wasn’t much. Most of the workers in the Mills were women and children; over 67% female by 1880. Back in 1860, the typical mill worker was a young unmarried Irish girl between the ages of 15 and 25. But by 1880, more than one third of the work force was now French Canadian. Two out of three workers, both French Canadian and Irish, were now female. Some of the departments were manned solely by children, some as young as nine.

In many families, having one’s child working was the difference between making it, or going into debt. Families were encouraged to having their children work in the plant, although they were not well paid. Children were required to go to school, most stopped by the time they were 10 or 12, because the need to work to help support the family was so strong. In some families, the entire family worked at the mill – men, women, and children. Children, with their speed, slight builds and nimble fingers, were invaluable for many positions on the spinning and weaving machines, able to scoot in and out, fixing threads and trouble shooting.

Many of the English weavers brought over by Robert Johnston were men. Like him, they had learned their trade in the English weaving mills from childhood. They had come with their families and were among the most skilled personnel in the entire operation, and drew the highest salaries. In 1880, only 16.6 % of the work force were males over 20. The average man made 75 cents for a 12 hour work day. The mule-spinners could make twice that.

Women who performed the same jobs as men in the plant were paid less than the men. But the highest paid jobs, such as the mule-spinners and weavers, were not open to women. An unskilled boy only made 30 cents a day, for a work day that lasted from 6 am to 6:30 pm. Everyone worked an exhausting 72 hour week, some for as low as fifty cents a day.

As bad as all of this sounds, it could have been much worse. In Robert Johnston, the manager of Harmony Mills, the workers had a sympathetic advocate. He was one of them, and had been a child worker and then a mule-spinner in a textile mill himself. He and his son, David John Johnston, who assisted, and then became Superintendent in 1866, were under great pressure to keep production and profits up and costs down.

As the technological advances in equipment meant that less people could do more work, demands for productivity increased. Harmony Mills was not only running under the pressure of its owners, it was in fierce competition from the mills in Lowell, Mass., Nashua, New Hampshire and Paterson, NJ. If they could sell their goods cheaper, then Harmony Mills would be in trouble, and everyone would be out of a job.

As the labor movement began to grow in factories all over the country, Harmony Mills was not immune to strikes. The first major strike was in 1858, which shut the plant down for three weeks. In the Depression of the early 1870s, people were just grateful to have jobs, but after the crisis was over, labor organizers began making headway in the Mill.

In 1878, the skilled mule-spinners formed their own union. A period of strikes and labor unrest took place in 1880, when a mass walk-out took place. As time passed, management threatened to throw people out of their company homes, and workers in the boardinghouses were told they wouldn’t be fed. This strike finally ended.

Two years later, an even worse strike took place, which affected the entire city, since so many people in Cohoes worked for Harmony. In the end, over a third of the workforce left Cohoes and never came back. The strike had the support of the ironworker’s union in Troy, which sent money and support. The strikers and their unions got support from labor unions and supporters all over the country. But the strikers were again forced from their housing, and this time, Swedish workers were brought in to work the abandoned machines. Finally, after almost a month, the workers couldn’t hold out any longer and returned to work. There were no more large strikes or labor problems again.

Robert Johnson was a paternalistic, but generally fair boss, who did much to make working and living at Harmony Mills as pleasant as possible, considering. He lived on the Hill and walked to work every day, and was always available for a conversation. He ran Sunday School classes in the building that housed his offices. His son, David John, was respected and liked, as well. Robert died at the age of 83, in 1890. David John died suddenly himself, only four years later.

His death was the beginning of the end of Harmony Mills. Several managers came afterward, including David J. Johnston’s son, David Stuart. The most skilled workers began leaving in droves as textile mills opened down South and elsewhere. David Stuart was able to stem the tide, but when he resigned in 1910, the company had lost much of its edge on the market.

In 1910, the Garner Company sold their interests in the company to the Draper Company of Massachusetts. They also sold the Cohoes Company and the Cohoes Power and Electric Light Company, to New York Power and Light. The water powered canal system was obsolete technology now, as electricity had replaced turbine water power. Most of the canals were now obsolete as well, and were filled in. Many of the buried conduits were used to run power lines, not water.

The modern equipment brought in by Draper helped them stay in competition, but they couldn’t fill all of the buildings anymore, and business was never the same. The Depression was the final blow, and in 1932, the great Harmony Mills ceased operation and began selling off its equipment and facilities. Much of the machinery and equipment was sold to Russia and the Far East. In 1937, the tenement houses were sold at auction for about half their worth. Many of the former mill workers were able to buy their homes. The mill buildings were also sold off at auction. Mill No. 3, that behemoth factory building which had been assessed for half a million dollars, was sold for $2,500.

Over the next seventy or so years, smaller companies worked out of the Harmony Mills buildings. Some were successful, others not. Cohoes, thankfully, did not tear down Harmony Mills, although there was serious talk about tearing down the millworker’s housing, and building modern public housing. Fortunately, with the help of preservationists and professors of architecture at Rensselaer Poly Tech, in Troy, that never happened. Mill No. 3 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. In 1988, the last big tenant at Mill No. 3; Barklay Home Products, went out of business. The complex began to deteriorate, and was mostly empty.

In 1995, Mill No. 2 burned to the ground. In 1998, a serious fire damaged Mill No. 1. That same year, the entire Harmony Mills complex was placed on the National Register. The report showed many empty buildings, some with broken widows and vacant interiors. Being on the National Register does not guarantee a new life. But fortunately, in this case, it helped. Developer Uri Kaufman bought Harmony Mills in 2000. He planned on turning the complex into luxury loft apartments, starting with the centerpiece of the Mills, the enormous Mill No. 3.

Mr. Kaufman specialized in industrial loft conversions, and had a proven track record, but this was the largest project he, or anyone else, had ever attempted. Thanks to the National Register status, there were substantial tax credits available, as well as other help from the city, state and other sources. But this would be a massive multi-million dollar project. At another time, as a follow-up, I’ll write about that process in more depth.

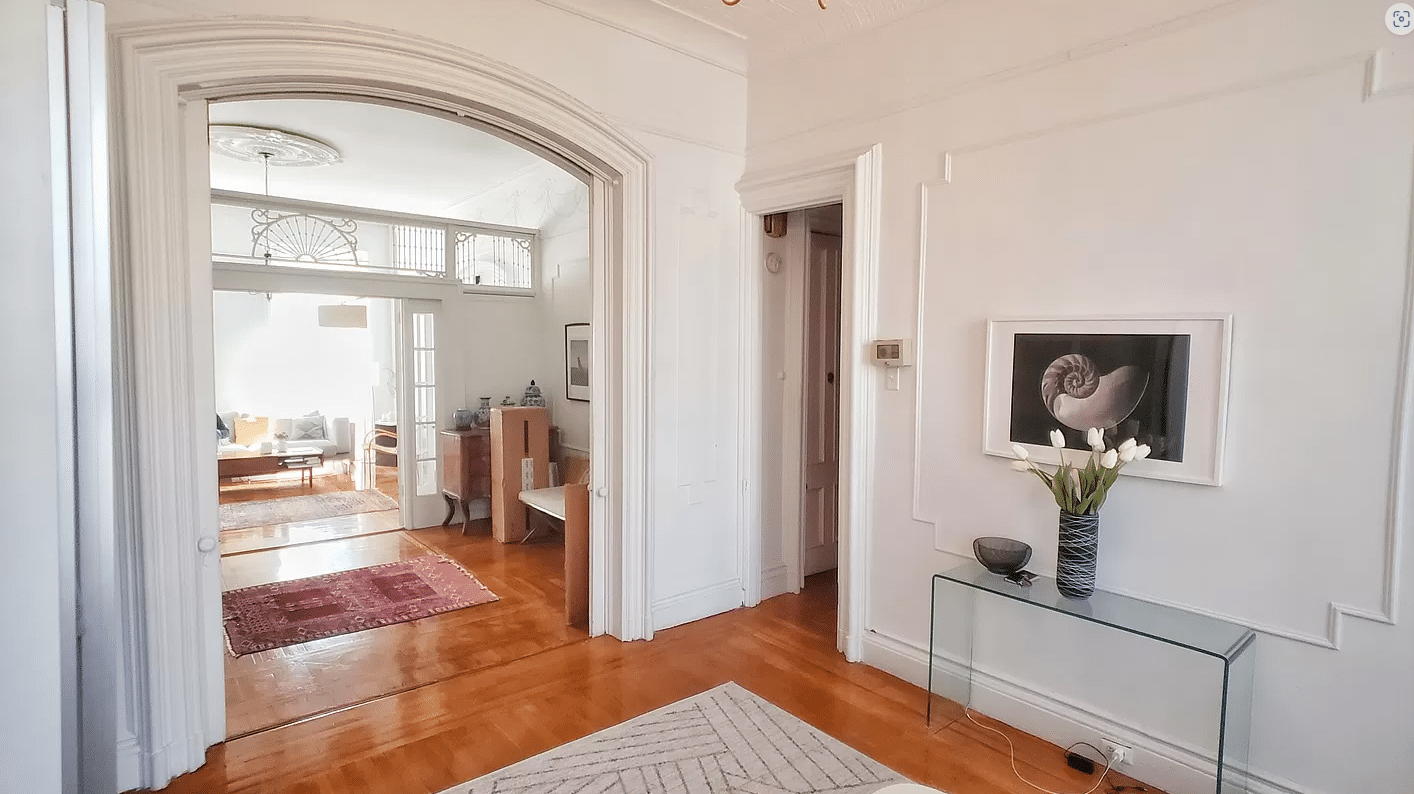

In 2005-2006, the first phase of the project created 96 apartments in the south end of the building. The second phase had an additional 135 apartments in the north end of the building. By the time the north end was ready, in 2010, the south end was completely rented. The north end conversion included a pool and spa and other luxury amenities, and had the best views, which overlook Cohoes Falls and the Mohawk River. This phase was completely occupied by 2012, and people were still coming.

A third phase – restoring Mills 1 and 4, began in 2013. Today, Mill 4 is done, 98% of its 33 apartments pre-leased before the building got its C of O. Sales are going on now for the newly completed Mill 1. Today, there are 332 loft apartments at Harmony Mills, and Mr. Kaufman is not done. In addition, a non-profit low income housing group called the Community Builders has renovated and leased 66 units in seven buildings in the former worker’s housing tenements nearby. There are more such plans for the future. As shown in the 2010 census, for the first time since 1930, the population of Cohoes has risen.

The adaptive use of Harmony Mills into housing and related amenities has been a poster child for such projects all over the country. Instead of a crumbling building with broken windows, the mill buildings today are as magnificent as they once were in their heyday. Built and re-built by the vision of remarkable men, and sustained by the labor of thousands of incredibly hard working men, women and children, Harmony Mills is a monument to American success, and the power of the manufacturing sector and its workers. It’s also about the determination to bring new life into the Spindle City, as Harmony Mills once again makes Cohoes proud. GMAP

Harmony Mills, Part One

Harmony Mills, Part Two

Harmony Mills, Part Three

The Lofts at Harmony Mills

(Photo: Mill No.3 taken from the park over the site of the original Erie Canal waterway. S.Spellen)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment