The Pope’s Mr. Pope: The Rise and Fall of the Pope Family Mansion on Bushwick Avenue

Few people who walk past are aware of the site’s rags to riches history or the family drama that unfolded on the corner of Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street.

The entry hall of the Pope mansion in Bushwick circa 1910. Photo by by H. G. Borgfeldt via Pope Mansion photograph collection, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History

One of our cultural icons is the self-made man or woman. We love to see stories of people who came from nothing, often from another country, worked hard, and with determination and a little luck, were in the right place at the right time to become incredibly successful, wealthy, and important. But, perversely, we also like stories in which successful people, their children, or other relatives fall from grace and prove they are just as flawed as the rest of us. The medium in which we follow those types of stories may have changed over time, but our fascination still remains strong to this day. This is the story of one of those families.

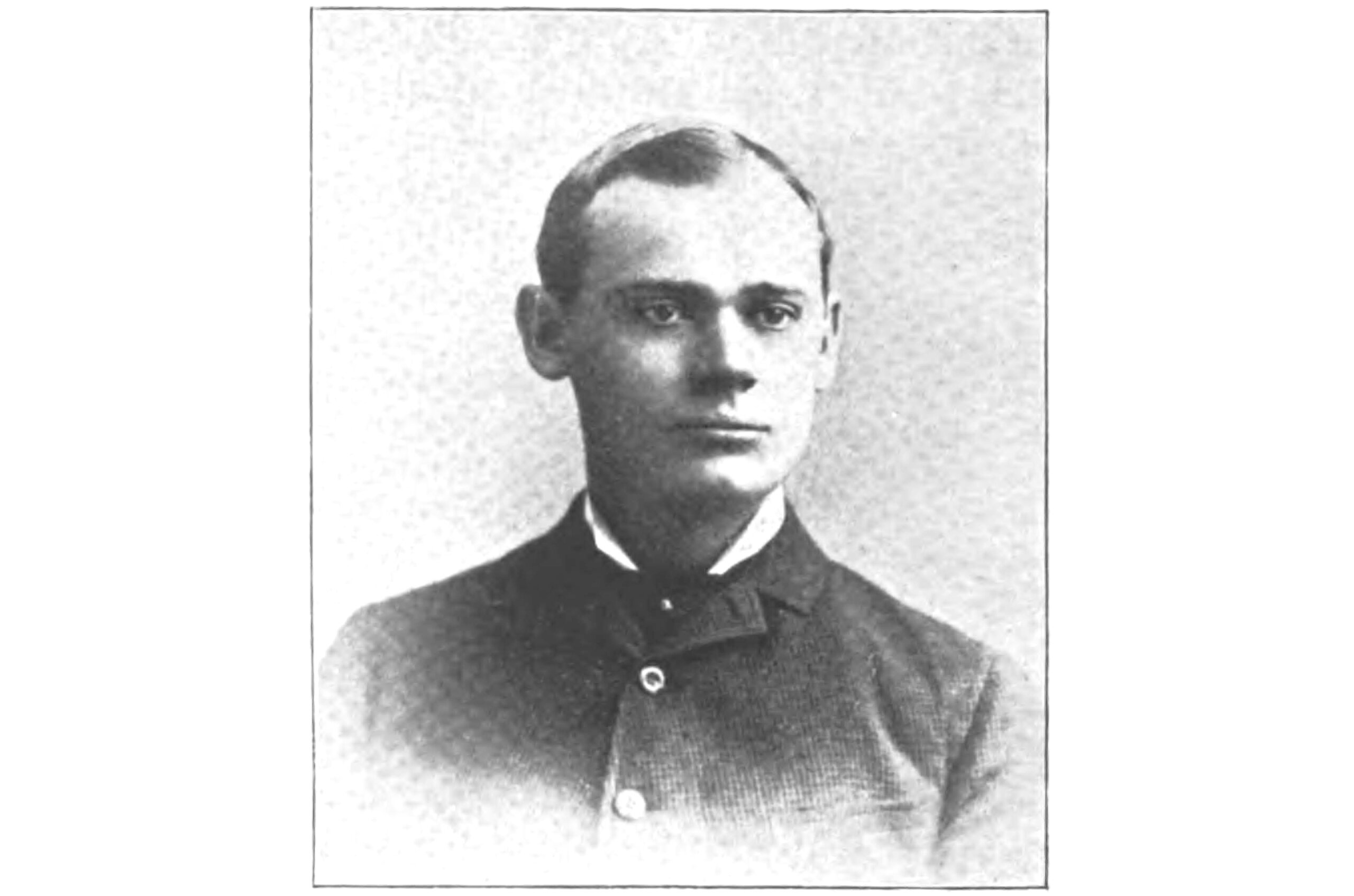

John Pope was a Brooklyn boy, born in the city in 1856. His parents were poor Bavarian immigrants and young John had to be a breadwinner at an early age. By the time he was in his teens he was working as a wagon boy on an express delivery wagon in Manhattan. Much like the delivery services of today, John would do rush deliveries. His customers were men of industry and commerce who needed their goods to go to their buyers, post haste.

Delivering anything in Manhattan in the post-Civil War years wasn’t any easier than it is today, and the time it took to get around probably hasn’t changed either. Young Pope became known as an industrious young man who didn’t wait around to be called to do something. He got impatient when he went to a business for a pickup and the goods weren’t ready. Instead of sitting there waiting, he would jump down and help load or unload, even going down into the warehouse himself to pack goods.

He delivered primarily for Manhattan tobacco merchants. Major Lewis Ginter was his largest client. Ginter represented Virginia tobacconist John F. Allen, one of the largest Richmond tobacco growers. Ginter, whose military rank was from the Confederate Army, was himself a New Yorker by birth and a Virginian by choice. During the course of the war and its aftermath, he had gained and lost several fortunes and was now working for Allen. He was impressed by young Pope’s initiatives and work ethic and took him under his wing.

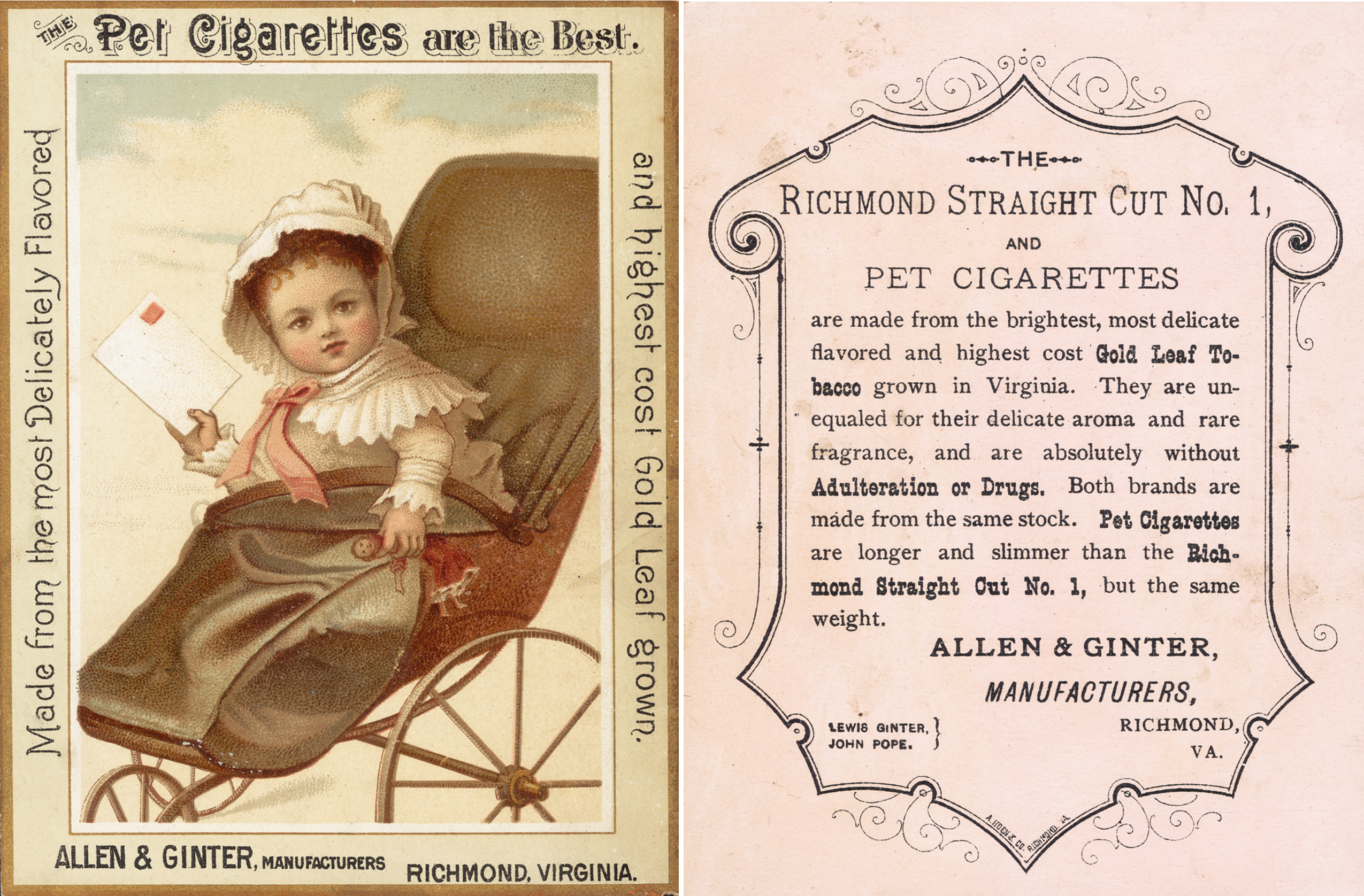

In 1874, Ginter took John down to the company’s Richmond, Virginia offices, where John was employed as a clerk. The Allen company manufactured chewing tobacco, pipe tobacco, and some cigars. But their fortunes were made when Ginter, now a partner, had them manufacture mild cigarettes made of local Virginia and North Carolina tobacco. Cigarettes weren’t that popular at the time and the existing ones were made from a stronger “Turkish” tobacco, imported for that purpose from Bulgaria, Greece, and the region. Ginter’s cigarettes were initially hand rolled, and although it took time for them to catch on, their popularity eventually vaulted the firm to success. It became one of the largest tobacco manufacturing companies.

Despite his lack of formal schooling, Pope rose through the company. In 1888, Allen retired, and John Pope became his sponsor’s business partner. He took the office of vice president. By 1900, he was also the president of the Crystal Ice Company, the James River Marl and Bone Phosphate Company, and the Powhatan Clay Manufacturing Company. In 1890 Allen & Gintner merged with several other tobacco companies and became the American Tobacco Company. By that time, they were producing thousands of cigarettes a day by machine. Pope remained the vice president of the American Tobacco Company for the rest of his life.

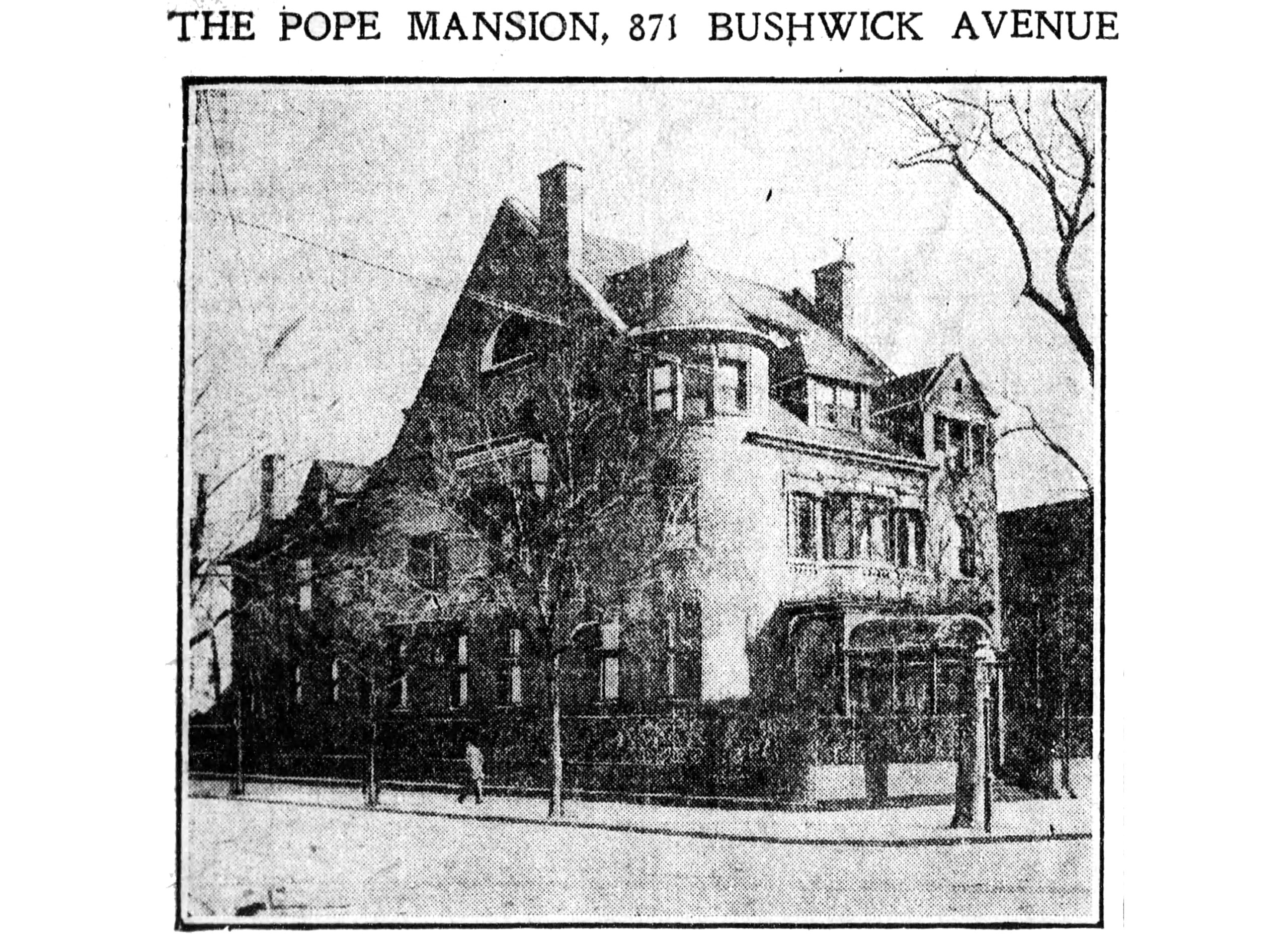

Now extremely wealthy, John Pope decided to come back to Brooklyn and spend some of wealth on his remaining family. He purchased a large plot of land on the corner of Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street, across from the Bushwick Congregational Church, and built one of the largest and grandest mansions in the neighborhood. Plans for the mansion were filed in 1893, and the building at 871 Bushwick Avenue was completed the next year. The architect, G.W. Parsons, designed a large three-story Romanesque Revival/Queen Anne palace that surpassed the homes of the wealthy local beer barons along Bushwick Avenue.

The house was built with the finest materials and the latest conventions of its day. Newspaper reports note that it had a center interior court, beautiful front and back gardens, and more. Photographs show that the house had all the elaborate woodwork, wainscoting, built-in cases, and architectural features of the period. The house had mahogany coffered ceilings in many of the public rooms and elaborate plaster ceilings and friezes in other rooms.

John never really lived there for any length of time. His principal home was in Richmond, where he lived with Lewis Ginter in a Romanesque Revival mansion, today part of the Virginia Commonwealth University. Both men were involved in developing a planned suburb now called Ginter Park. Their home there, in the much renovated house of a former plantation, included such amenities as a private barbershop and a bowling alley. They extended Richmond’s commuter railway to their suburb, creating the nation’s first large-scale electric streetcar system. Both men were very philanthropic, donating generously to a number of causes.

But that was not to last. In April of 1896, John was in New York City when he began complaining of a sore throat and laryngitis. He returned to Richmond where it got worse. Doctors confirmed the seriousness of the case, and specialists operated, but John Pope was dead in a week, succumbing to blood poisoning from an abscess in his throat. His friends and colleagues were devastated: He was only 40. Major Ginter, who shared his house and his life with Pope in that Victorian way where certain things were never spoken of, gave his burial plot for Pope’s burial in Richmond. He never recovered from the death and died himself a year later.

John Pope left a detailed will. In addition to the businesses already mentioned, he was also the director of two banks in Virginia and had significant equity in his real estate ventures with Lewis Ginter. The estate was worth over $2 million, which would be around $75 million in today’s money. He left his considerable fortune primarily to his younger brother, George, and their three sisters. The house was given equally to all four siblings. The three sisters had $25,000 in cash each, along with generous stock and securities portfolios adding up to another $125,000. George was given the remainder of the money after all the bequests had been filled, which added up to more than a million dollars in cash and assets. George, who had been comfortably upper middle class, was now RICH.

Before his brother’s death, George was a brick manufacturer and owned the Manhattan Enamel Brick Company. That fact was barely mentioned in later press, because he went on a spending and giving spree the likes of which hadn’t been seen in Brooklyn before. His charitable work was primarily for the Catholic Church. He was a devout Catholic and donated a lot of money to Church causes. He made some large gifts to local Catholic churches, too. He donated an ornate marble altar and a pipe organ to St. John the Baptist Church on Willoughby and Sumner avenues, as well as a full pipe organ to St. Barbara’s church on Bleeker Street in Bushwick.

He donated to the Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged just down the street from him, and the Sisters of Charity. His generosity was so extensive that in 1902, Pope Leo XIII made him a Papal Knight of the Order of St. Gregory, an honor that went to very few. At 33, he was the youngest man to ever become a Knight Commander and only the third American. The investiture took place at St. John the Baptist, a magnificently large church, and was a very simple ceremony presided over by the Bishop of Brooklyn. He received a gold and red enameled cross with a picture of St. Gregory in the center, suspended from crimson and yellow ribbons, the colors of the order. His knighthood gave him access to the Vatican, should he be in Rome.

George didn’t give it all away. He also never married and devoted his time and money to collecting things for the house. He spent a lot of money on new furniture, fancy gardens, and stained glass windows, some of which may have been by Tiffany. He started collecting art, filling the house with all kinds of artwork, and had special lighting put in which enhanced his paintings. He collected tapestries and became a connoisseur of antique Persian carpets. He had dozens of them. He had an extensive collection of music boxes, bought the latest gramophones and recordings, several pianos, and was known to have an impressive collection of antique laces and embroidery.

He upgraded all the light fixtures in the house and had a pipe organ installed in one room. He loved organ music, had donated at least two organs, and loved to play himself. The only photograph of George available shows him at that organ, taken in 1902. Many of the rooms in the house were also photographed that year and are now in the Pope Collection of the Center For Brooklyn History. They show what we would consider today to be dark, cluttered, and overdone rooms with tons of bric-a-brac. Very few people saw all this splendor, as George was a recluse and had very few guests.

By the time he was honored by the Pope, he and two of his sisters had been living in the house for a few years. The third sister was living with her family elsewhere. But the house on Bushwick Avenue was full. Living amidst the stuff was his sister Maggie, who was 36, and widowed sister Kunigunda Mullin, 38. She had two children, James and Margery, who were teenagers. Another relative, Dorothea Drescher, 82, lived there too. She died soon after the 1900 census. Three live-in servants took care of them all: Thomas Gilbert, 29, the butler; Katie Working, 35, the maid; and Marie Hirsch, 30, the Austrian cook.

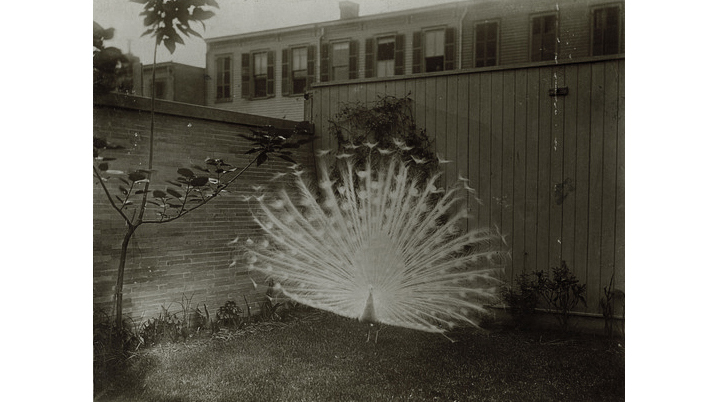

Kunigunda (love the name) became very unhappy in the house. She could see how much George was spending on his lavish lifestyle and was worried that he was going to spend her children’s inheritance. By 1908 he had already spent $750,000 (many millions today) on art and everything else and was still buying more. He built five greenhouses for his plant collections on the grounds and bought a beautiful white peacock to roam freely, as was the custom on grand European estates. The peacock may have been the last straw for Kunigunda. George bought it for $140. That’s a $5,000 bird in today’s money.

By 1909, no solution had been reached between the two. Maggie was totally dependent on him and wasn’t going to get involved. Margery, the daughter, married and moved out, leaving son James with his mother in the house. Kunigunda hired a lawyer named J. Hunter Lack who tried for a year to arrange an amicable solution. None could be reached, and a very public lawsuit ensued.

It was newspaper gold. Who wouldn’t want to know why a wealthy widow living in a splendid mansion, going on trips overseas, having the finest of everything and otherwise able to do whatever she wanted would sue her much wealthier younger brother because he spent too much?

The heart of the matter was that George received the bulk of the estate and controlled the rest of his brother’s bequests, including the stocks and securities left to them all. She and her sisters were given a generous allowance, quite generous for the day, but they did not control their part of the fortune. Kunigunda wanted to separate herself from George’s financial control and collect her share of stocks and securities and also be released from sharing the cost of the household expenses. The house, which was left to all of them, was solely in George’s name, but she and her sisters paid for its upkeep from their inheritance. She was especially angry that her share helped pay for that damn peacock, which she was quoted as saying was “worse than worthless.” (It was later given away, after the rich neighbors complained it made too much noise.)

George’s lawyers explained that Mr. Pope always wanted to be fair with his sisters. They made their decisions the German way, he said, with a family council. They had all agreed that George would handle the monies. But now, 12 years after John Pope’s death, that wasn’t good enough for Kunigunda. Mr. Lack, her lawyer, countered that those decisions were made before George began his 12-year spending spree, and his client was afraid that the expenses would soon eat into her children’s inheritance.

George offered to have the house partitioned, but Kunigunda didn’t want to do that. One, it was too expensive for her to take care of (she probably hated all the stuff) and two, even if it was divided after that, his name would still be the only one on the deed. She would have no legal right to the property. She told the judge that she no longer wanted to live as though she had a fortune when she actually didn’t. Bottom line, she wanted the shares her brother left her, which had greatly appreciated in the last nine years, and wanted to leave her gilded cage.

George, on his part, insisted that he had always been fair, and he offered an accounting to show how much of the money had been spent. He said that the funds for indulging in his collecting and interior decoration hobbies came out of his own money that he had before John died. He refused to sign over his sister’s securities because he didn’t think that was the right way for a brother and sister to settle their differences. He also didn’t understand why she was unhappy: She and her son lived in luxury, they had servants, they traveled, and all that came largely from George’s fortune. David Mullin also had been hired as a clerk in George’s brick company.

The judge ruled for Kunigunda, and George had to give her the securities she was owed. The next year, in 1910, she and her son were living near the Parade Grounds in Flatbush in a much more modest limestone row house on a quiet street, and her name disappeared from the press for many years.

George and his sister continued to live on Bushwick Avenue. Unfortunately, the men in his family died young. George was at his winter home in New Jersey when he became ill. After a long illness, he died in Atlantic City in late November, 1917. He was 48. Most of his obituaries spoke more about his brother, his sister’s lawsuit, and his lavish home and varied collections than they did about him. It was estimated that the goods and the house were worth over $2 million. The sisters no doubt sold almost everything, and the house was locked up and remained empty for three years.

At the time of his death, he and sister Margaret were rattling around in the house alone; there were no live-in servants. George is buried in St. John’s Catholic Cemetery in Queens. He lies under a large slab with a cross covering most of it, and the inscription “At Rest.” Behind that is a statue of Christ blessing him. Another granite slab behind Christ is carved with a scroll with George’s name and dates.

His sister Margaret is buried here too. She died in 1936 after a long life, although she was crippled by the time she died. But even quiet Margaret had drama after her death. She was supposed to have had a $3 million estate and left much of it to her longtime secretary, Otto Schneider, who also handled all her finances. But when the assets were added up, that $3 million had shrunk to $30,000. The Crown Heights house Margaret had been living in since selling the Bushwick mansion was now occupied by the Schneiders.

The only surviving member of the siblings, 74-year-old Kunigunda, went to court to contest the will. She alleged Schneider mismanaged her sister’s affairs and either lost or took the money. We’ll never know, as Kunigunda lost the case, and since she wasn’t in the will (Margaret never got over the lawsuit, apparently), it all went to Schneider. Kunigunda died in 1939 at 78 years old. She is buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn, a distance away from her two siblings.

Back in 1920, the mansion was sold to the Jewish Home for the Aged and Infirm, which purchased the house for $150,000 and planned on investing the same amount of money in renovations and an addition in the rear. The organization, located in Mount Vernon, New York, wanted to establish a home in Brooklyn, which had a large Jewish population in the borough and was in need of a home for seniors. Workmen came in and started the renovations.

To everyone’s surprise, it was discovered that many of the house’s elaborate chandeliers were 22 carat gold and worth a lot of money. That was certainly a pleasant finding for the new owners. The surviving sisters were not aware of it either. In some rooms, the windows had George’s monogram etched into every pane. Workmen got another surprise when they opened what looked like a closet off the dining room and found a massive and impregnable vault, where George must have kept his most valuable treasures.

They also found George’s beloved pipe organ, which was valued at $10,000. The home planned to convert it to electricity and keep it for the enjoyment of the residents. They intended to preserve the decorative moldings and ceiling details as well. One of George’s horticultural acquisitions was an extensive bonsai collection, which the papers called “little trees.” They were rescued, but the large pool stocked with koi did not endure, as the Home needed to expand the dwelling with a wing in the back.

The Pope mansion served the Hebrew Home, now Menorah Home, until the 1950s, when they decided that the house was too small, and they needed a larger modern facility. The mansion that John Pope built for his siblings — the house that was home to George Pope and his collections, his pipe organ, two of his sisters, his niece and nephew, and the white peacock — was replaced by a five-story Moderne-style institutional building. It has a rounded prow at the corner, a sleek unornamented facade, and is not the worst looking building on Bushwick Avenue.

It extends down Himrod for half the block, emphasizing how large the Pope estate was. It was no doubt practical, easier for the elderly population, and housed far more people than the storied monument to excess. Today, the building belongs to the Bushwick Realty Holdings LLC. Few people who walk past are aware of the site’s rags to riches history, the knighthood by the Pope of a Pope, and the family drama that unfolded in the mansion that once stood on the corner of Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street.

Related Stories

- A Quick History of the Dining Room and Its Decoration in Brooklyn and Beyond

- ‘I Only Do Big Things’: Woman, Architect, and Brooklynite Fay Kellogg

- Rene Chambellan, Art Deco Architecture’s Master Sculptor, in Brooklyn and Beyond

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

I very much enjoyed reading this article on the Pope mansion. Such a shame that so many beautiful old homes have been lost. The author took delight with the name of one of Mr. Pope’s sisters, “Kunigunde”. The name is Germanic in origin, one prominent woman with that name being the sister of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. So there. 🙂

Odd – I signed in using my Google account, no idea why my name didn’t display. It’s Kai Thorsen.

Thank you for reading and your comments. I’ll report the bug with the name display to our tech folks.