The Remarkable Story of Crown Heights' Zion Home for Aged Colored People

African Americans in the late 19th century were determined to take care of their indigent elderly themselves.

Residents of the Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People Elizabeth Jackson, age 95, and Fred Marshal, age 87, hold hands in 1951. Photo via Brooklyn Daily Eagle photographs, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History

Imagine being old and no longer able to work, with no family and no wealth of any kind. In the late 19th century, when our Brooklyn neighborhoods were being developed, society had no social safety net. There was no Social Security, no Medicare, and no food stamps. There were no social workers or Meals on Wheels. If you had no independent funds of your own and no family to support you, elderly people were left to the mercy of private charity and public almshouses and insane asylums. The latter were simply awful on so many levels, but that’s another story.

Old age homes were primarily established by the various faiths and denominations. Each group built and ran the various homes according to their particular rules and regulations, and most were funded by groups of wealthy patrons. Many people, through religious conviction or just a sense of doing what was right, had a real desire to help those less fortunate than themselves. Charity towards the poor was seen as a tangible sign of being morally upright and worthy of one’s riches. Being seen as stingy and uncharitable was not a good look, especially in the highest realms of society.

Each group, denomination, or faith took care of their own. Baptists took care of elderly Baptists; Methodists, Presbyterians, and Catholics took care of their own as well. Because of prejudice and a desire to make sure their religious and cultural needs were fulfilled, Jewish philanthropists also established their own facilities. Everyone stuck to their own “tribe.”

The requirements for admission to one of these homes were very strict. One had to be a member of that faith “in good standing,” an applicant had to have no other family who could house or take care of them and, if physically possible, they had to be able to contribute to the upkeep of the facility through some kind of work. Housekeeping chores were always needed, and making crafts and products that could be sold to raise money was a tried and true endeavor. Separate facilities were sometimes built for men or women but most homes accepted both men and women. There were always more women than men.

The result was the construction and operation of a number of old age homes both large and small. Typically, a home would be established in a row house or mansion, and as the number of people needing shelter increased, the group would fundraise and build a much larger facility. In Brooklyn, many of these larger complexes were built in developing neighborhoods when land was still plentiful and relatively cheap.

Just as one would not expect to find elderly Methodists in a Catholic institution, it was understood that all these facilities were for white people only. Black people, at the bottom of the societal ladder, were not welcome or allowed, except as servants. African Americans in the late 19th century realized that and were determined to take care of their indigent elderly themselves. Because of that need, the Zion Home for Colored People was established. It was in the Black community of Weeksville and was part of that town’s social lifeline.

The Zion Home is established

Weeksville, as everyone should know by now, was an independent town established by African Americans in 1839. Land was purchased from the Lefferts estate by several established Black leaders who then sold the plots to other African Americans. The lots were located at the eastern border of the city of Brooklyn, which at the time did not include New Lots, a part of independent Flatbush. James Weeks, a longshoreman, was one of the first buyers and the town of Weeksville grew up around his home and property. Contrary to some uninformed sources, neither James Weeks nor the men who bought the Lefferts land were ever enslaved by the Lefferts or anyone else.

The need for one’s own town was great, as freeborn Black people were not accorded the same rights as whites and were not welcome in most businesses, entertainment venues, or churches. Owning property was especially important, as male landowners could vote. As the town grew after the Civil War, Weeksville had homes, its own Black-owned businesses, churches, a public school, orphanage, and cemetery.

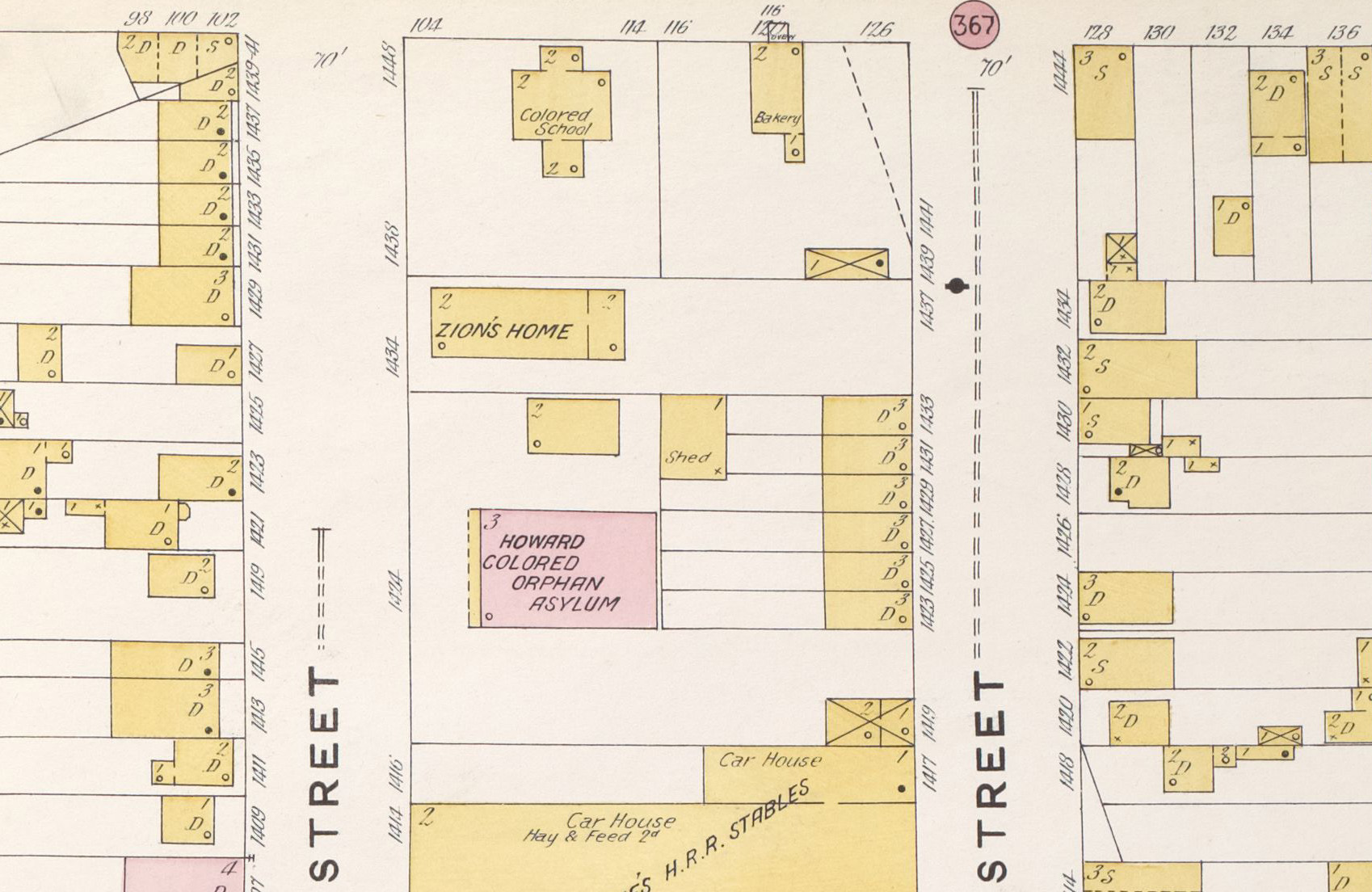

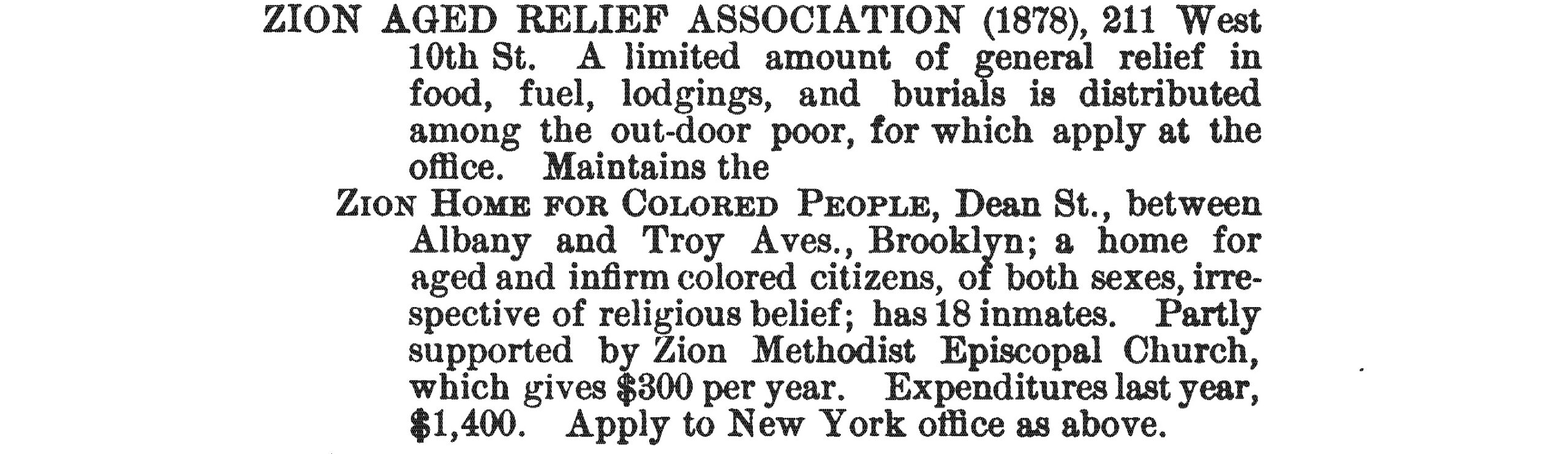

The Howard Colored Orphan Asylum was established first, in 1866, designed to meet the need of housing Black children who were orphans or whose mothers were in need. A home for those at the end of their lives was the next step. In 1869, members of the Zion African American Methodist Episcopal Church in Manhattan formed the Zion Aged Relief Association, whose purpose was to establish an old age facility. Weeksville was chosen as the best site for the home.

In 1874, the Zion Home for Colored People opened in a large frame building on Dean Street, near Troy Avenue. A chapel was established in the building, as well as the expected accommodations and public rooms. It was on the same block as the Howard Orphan Asylum, Colored School No. 2, and the African Civilization Society. The next year there were more than 50 men and women living and working in the home, which was sustained by funds raised by both Black and white supporters.

In 1875, the Brooklyn Eagle noted the institution was celebrating its first anniversary with sermons and speeches, choirs singing, and a nice meal. Of the home the Eagle noted, “Over 50 superannuated and decrepit colored people of both sexes now occupy the handsome edifice which has within a given time been completed. It is a worthy institution.”

The residents of the home were charged $150 for a lifetime place in the home, plus $8 a month board. Most of the women there at the time were quite elderly; several were 100 years old or more. They were tough, having survived lifetimes of toil, and were alive when slavery was still legal in New York State. Charlotte Sipkins, born enslaved in 1784, died at the home 100 years later. She had been married in 1811 and widowed in 1828. Another resident, Lida Alford, made the papers at her passing in 1888. She was 103 years, one month, and 11 days old. The notice said she died of “senile gangrene,” a medical term no longer in use that referred to deterioration of the walls of blood vessels in extremities and led to tissue death.

In 1880, an election year, those running the home rented the chapel for rallies supporting the Democratic party, which at the time was no friend of Black folks. The notices for the meetings had the wrong street, posting that it was on Bergen Street, not Dean. One irate African American reader of the Brooklyn Union newspaper wrote in disgust, “No doubt they allow this to cover their shame for letting the chapel of the Old People’s Home to the party who, since the war, have sought to destroy and render non-effective the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution.”

He or she went on to say that the speeches were a “great annoyance of the aged colored people who are obliged to listen to the desperate statements made by the party that had enslaved their fathers, mothers, and sisters, and the same party which would be willing to sustain a Solid South and even should reinstate chattel slavery and the whipping post.”

More than likely, the administration of the home allowed the rentals not because of political ideology, but of necessity. They really needed the money to keep going. The Zion Home was an older wood frame building. Several descriptions of the day describe a three-story factory building of some kind. It would have to be large enough to hold a chapel for gatherings and house 50 people and facilities. The home was very expensive to run and depended solely on donations from the greater community and the generosity of well-to-do white patrons.

By the late 1880s, Zion was in deep financial trouble. They were down to 29 residents and donations were drying up. The building was becoming seriously run down and the elderly occupants often didn’t have enough food to eat or heat in the winter. Articles in the papers were very damning, with reports of the roof leaking water onto beds, starving elderly and helpless people, and a staff that had not been paid in months. The matron was often seen going door to door with a basket begging for food. A series of fund-raising events were planned, with Black and white church committees joining to raise money. They kept the place going but were never enough.

By the late 1880s the City of Brooklyn established the Brooklyn Board of Charities. Most of the city’s legitimate charities fell under their purview. The BBC was a city agency and had an annual budget of taxpayer money that was disseminated to various charities and institutions. They were charged with making sure their money was properly spent and accounted for. Zion Home was on their list.

The headline of a December 6, 1888, story in the Brooklyn Union newspaper read “Badly Fed Old Women.” The article began by describing the building as “ramshackle,” but focused on the lack of good meals, or even just food. “For months at a time, it is said, butter is unknown in the home, and weeks have passed without meat being placed on the table. The neighbors here often have been called upon for food by those who are able to get out of the house, but how those who are so feeble that they are unable to leave it manage to subsist is a matter of wonder.”

An organization of religious women called the King’s Daughters took a great interest in the home and began working with them. They were appalled at the conditions. They reported that a section of the foundation of the building was giving way. The Board of Trustees was notified but did nothing. Finally, the city told them that if they didn’t act, the city would do it, and charge them accordingly. They got it fixed, but in the meantime, the roof was leaking and was never repaired.

It was apparent that the home was very attractive to thieves and scam artists. The AMEZ Board was in Manhattan and seemed to have abrogated its responsibilities. Often money or goods earmarked for the home would never arrive, leaving the residents suffering. The funds for a large coal delivery never made it to the coal dealer. One of the managers of the home told the Daughters that she had collected enough money to pay for ice for the home for a year. It turned out that the home didn’t use ice.

A doctor claiming to have called upon patients at Zion submitted a bill for services to the BBC. It turned out he had never visited the place. Another Brooklyn man collecting for the home thanked the people of Brooklyn for their donation. He didn’t have any connection to the home and they never received any money. The King’s Daughters were disgusted and stopped work, calling upon the city to do something about the Zion Home for Colored People.

The troubles at the home made the papers often. That was cause for the racists in Brooklyn to rear their heads and complain. One such individual wrote to the Brooklyn Eagle’s Letters to the Editor column in 1891. He complained that he was tired of reading about Zion Home. He stated that there were enough wealthy men of color who could take care of the place without the help of the white population. Where were they, he asked. Plus, “There is no possible excuse for such a state of things when on any day of the year once can see a score or more idle, lounging colored women on Atlantic, Troy, and Utica avenues, just in the vicinity of the home.”

He went on to say, “Thousands of precious lives were sacrificed to emancipate these people, and what have they done for themselves? Literally nothing. While hankering after the privileges of the whites, when they are accorded them, they care not for their own race, as white people do, but lie down in idleness and filth waiting for the white trash, so they are wont to call us, to take our money, our time, and more, to carry them still as a burden.”

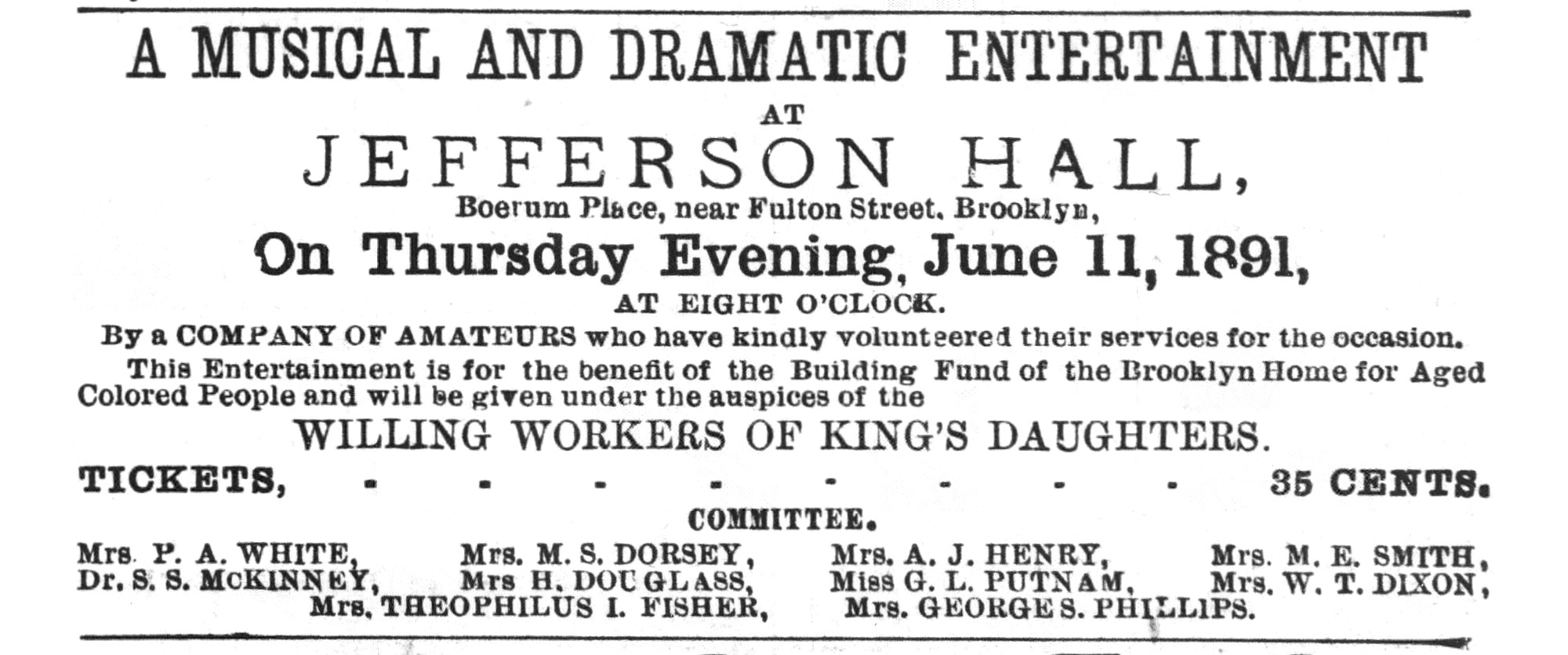

The plight of those frail elderly people still tugged at the hearts of the King’s Daughters. Founded in New York City in 1886, they were an ecumenical organization of church women both white and Black, dedicated to being a “sisterhood of service.” The organization grew to have chapters in 26 states and in nations around the world. In December 1890, 250 circles of the Daughters met in Brooklyn, representing many denominations and individual churches, including the mainstream Black churches. The convocation was blessed by male ministers, including Reverend Dixon of the Concord Baptist Church, one of Brooklyn’s largest African American churches. But the group’s leadership, membership, and decision makers were all female, headed by Mrs. Margaret Bottome, the founder of the Daughters, and a Methodist.

“The women inmates of the Home are our friends in Black, and to devise means for caring for them is our purpose in coming together tonight,” Mrs. Bottome told the group. Several other Black ministers spoke, including Reverend Walters of the AMEZ church that founded Zion. He explained why they weren’t able to keep it up and the problems they had with the old building. The leadership collected a thousand dollars that night and resolved to raise money for upkeep while also fundraising to build a new home.

That spring, the Daughters were incorporated and elected new officers and appointed an advisory board. It included African American members such as Reverend William Dixon from Concord Baptist and Charles Dorsey, the principal of P.S. 67. A board of managers was chosen to run the home, which also included African Americans. Mrs. Philip A. White, the wife of the first African American member of the school board, and Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward, the first African American female medical doctor in New York State, were board members. Dr. Steward was one of the daughters of Sylvanus Smith, who sold James Weeks his land, and was herself raised in Weeksville.

The influx of money was immediately visible at the home. Visitors noted that repairs had been made, the walls painted and wallpapered, and new mattresses were on the beds. The residents were getting three nutritious meals a day and appeared happy for the first time in years. “You cannot converse with these old women at the home without having an inspiration,” said Reverend Dixon. “It brings tears to my eyes, and my heart glows with pride when I think of their records. God bless the King’s Daughters.”

After making sure the residents’ immediate needs were being taken care of, the Daughters and their allies formulated a plan. In 1892 they moved the institution out of the building, which had been condemned, to an interim facility at 1888 Atlantic Avenue, which was only a few blocks from Dean Street. They then began almost 10 years of fundraising for continued upkeep and a new home. They sponsored fairs, strawberry festivals, held donation pledge events, musical events, and more.

Those who visited the home in those years marveled at how well it was run, and how well everyone — administration, staff, and occupants — got along. One of Zion’s most famous residents was also the president of the King’s Daughters Circle at the Home. Her name was Aunt Jane Brown, and her birthday in 1896 was the occasion of a reception and bazaar. She was 103. Despite being blind, she spent most of her time sewing quilts and hemming towels for the bazaars to raise money. She probably ran her Circle with an iron fist. Jane Brown didn’t live to move into her new home; she died in 1896 at the age of 105. It was said that she was mentally alert to the end.

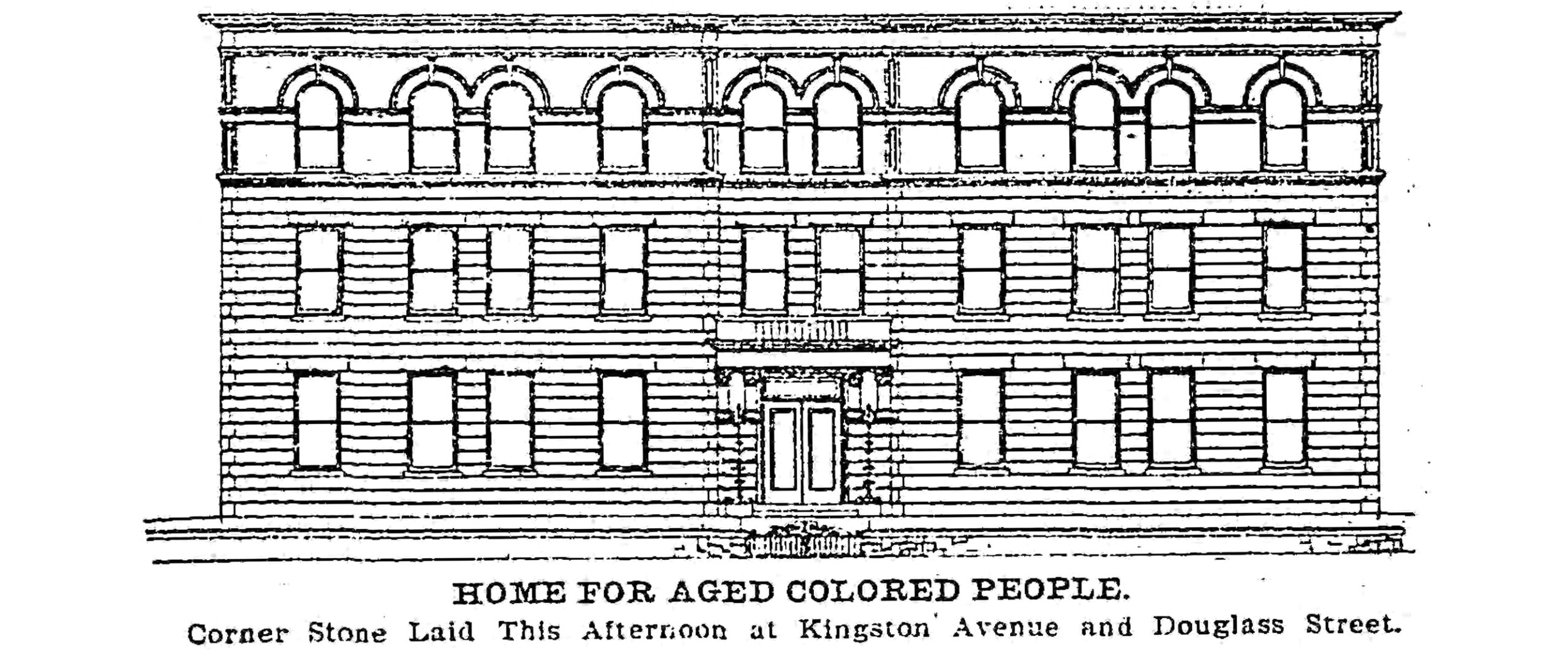

By 1897, the corporation purchased a large plot of land on the corner of Kingston Avenue and Douglass Street (today’s St. John Place). The address was 243 Kingston Avenue. One of the leaders of the Daughters was Mrs. George Stone. She became the project manager for the new build. Her husband, George, was a very successful builder and developer, and her son was an architect. Both volunteered their services, and designed and constructed the home without compensation. So did Cranford Brothers, a local plumbing company.

The ceremonial laying of the cornerstone would take place on July 24th, 1899, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported. “All Long Island” would be represented, said the paper. Three local ministers, two of them African American, participated in the ceremony while tenor Harry T. Burleigh of St. George’s Episcopal Church sang. (African American musician Burleigh would go on to become one of the greatest collectors and arrangers of Negro Spirituals. If you’ve heard traditional Negro Spirituals in concert, chances are he did the arrangement.)

The three-story-and-a-basement structure was brick with gray limestone trim, designed in the Renaissance Revival style. It was intended to house 40 residents and had steam heat and modern plumbing. Its ample surrounding grounds would become a park for the residents. Various churches, individuals, and Circles donated funds and materials to furnish the rooms. The furnishings included the necessities plus decorative objects to make the spaces homey and comfortable. At the time the home opened, residents numbered 25, including five men.

The Home corporation raised enough money to pay for the land and most of the building. It was thought the property would be finished debt free, but they ended up taking out a small mortgage. The opening ceremonies took place on January 26, 1900, with speeches and singing, refreshments, and tours of the facilities. The old folks were on hand, as were the ladies and gentlemen responsible. Black and white mixed together to celebrate the momentous occasion. The Brooklyn Citizen printed a sketch of the building and listed everyone — hundreds of ladies and a few men — on the various committees.

Sadly, the man responsible for the actual building did not live to see it operate for very long. George Henry Stone passed away in October 1900. He was 70 and died suddenly at home, which was a few blocks away at 1354 Dean Street. His obituary noted that he had always been active in church work and had conducted several local missions reaching out to underserved youth. He established the Faith Mission in Greenpoint and was its superintendent for 30 years. He organized and ran a Sunday school program at the Zion Home before committing to building the new facility, where he worked tirelessly until his death. His wife and son took over his work and were active for many years in church activities.

Over the years, the press expressed interest in the home. The papers told stories of the residents, several of whom had been enslaved earlier in life. One man, Mr. Adams, had escaped north and had been a servant in a New York home. In his old age, he was learning how to read, as he wanted to read the Bible. Another resident, Mrs. Serrington, had been born a slave and was given as a wedding present to her owner’s daughter. She was freed as an adult and married a Methodist minister. In her later years, she still visited the daughter, whom she called “her little girl,” although the woman was now 79 years old herself.

Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward sat on the board of directors and remained the house physician for the home, now called the Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People, until 1906, when she and her husband, Theophilus Gould Steward, were both called to jobs at the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s Wilberforce College in Ohio. Dr. Smith was the college physician. She was very active in African American women’s organizations and advocated for women’s suffrage. Her work took her around the country and to Europe. However, Dr. Steward died suddenly in 1918 in Ohio. She was returned to her beloved Brooklyn and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

As the 20th century progressed, Weeksville and its institutions slowly disappeared and were swallowed up by a developing Brooklyn. The Howard Colored Orphan Asylum sold its Dean Street building in 1911 and relocated to a work farm on Long Island. The building was torn down for the expansion of a trolley repair yard. The Colored School was incorporated into the public school system as P.S. 83, and a new building was constructed in 1923. The houses of Weeksville were torn down or gradually absorbed into what is now Crown Heights as the century progressed, but the four Hunterfly Road houses remained. They became the nucleus of the Weeksville Heritage Center, first established as the Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford Stuyvesant History in 1971.

Today, the Brooklyn Home is still standing and in operation. Modern new additions were built in 1982, taking up the entirety of the garden space, but allowing for 80 apartments in the complex. The combined buildings form a square with an enclosed center space providing natural light and ventilation to all units. The home is open to any senior regardless of race or religion.

Most of the large institutions built in the late 19th and early 20th century are now gone from central Brooklyn. The former Methodist Home for the Aged on nearby Park Place and New York Avenue and this former Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People are the only two buildings remaining. The home stands just outside of Phase 3 of the Crown Heights North Historic District. Its importance as a significant component of Brooklyn’s African American history, as well as its design and condition, make it landmark worthy. Although the additions to the structure obscure the east side and rear of the original building, the western side and the front facade are largely original and convey the beauty and purpose of the building. It should be landmarked and its history better known and celebrated.

Related Stories

- The Weeksville Heritage Center Looks to the Future With a Focus on Art and Community

- The Hiram S. Thomas Story: Brownstones, Potato Chips, Black Excellence in 19th Century Brooklyn

- A Brownstone for a Remarkable Woman, Brookyn’s Pioneering Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment