Journey by Faith: The Story of Brooklyn's Black Churches

For Brooklyn’s Black churches founded before the Civil War, the fight for freedom for all was (and is) crucial to their credo and their existence.

The Bridge Street AWME Church at 277 Stuyvesant Avenue, on the corner of Jefferson Avenue, in Bed Stuy, in 2022. Photo by Susan De Vries

“We’ve come this far by faith, leaning on the Lord.

Trusting in his holy word, he’s never failed me yet.

Oh, can’t turn around, we’ve come this far by faith.”

— Traditional Black church hymn by Albert Goodson, 1956

By the early 19th century, the town of Brooklyn lay nestled on the shore of the East River in what is today Dumbo. Not yet a city, it was still a collection of wood-framed buildings, with businesses and industry scattered among the taverns, churches, and homes. These early Brooklynites were from all walks of life and social classes and included a population of enslaved African Americans, as well as a community of free Black people. The latter included men and women who were employed as domestics and general laborers, as well as those who had their own businesses as rope makers, shoemakers, barbers, house painters, laundresses, and more.

Everyone encountered everyone else on the muddy streets of town, a growing population mixing slave and free, recent immigrants, sailors from other lands, and native-born whites. But this proximity ended at the doors of local churches. They were segregated by race, with the white congregations sitting in the pews downstairs and the Black congregations relegated to the upper galleries or in the back of the church. Black Christians were not allowed to participate in any part of church life other than attendance.

The First Methodist Episcopal Church of Brooklyn on Sands Street was one of early Brooklyn’s largest congregations. The entry ramps to the Brooklyn Bridge and former Jehovah’s Witnesses factories long ago replaced this entire neighborhood. As more and more free African Americans moved into the area, they looked for a place to worship and began attending services at Sands Street Methodist, as the church was commonly called.

The white congregation was not pleased to see Black people in their pews and began charging African Americans, and no one else, $10 a quarter to attend services. To make matters worse, the minister at the time, Reverend Alexander McCaine, was quite publicly pro-slavery. Who wants to pay to sit up in the airless balcony and then be forced to listen to sermons about the Biblical justifications of enslaving your people? Not these Black Methodists.

They withdrew en masse and began holding services in their homes. At the same time, they sent a delegation to Philadelphia to get advice and the blessings of the Reverend Richard Allen, founder of the first African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in that city in 1794. The Brooklynites wanted official permission to start an AME church. The men formed a board of trustees and submitted papers with the state for incorporation.

Their new church was called the African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church (AWME). The name honored John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. Church members tithed 50 cents a month, held fundraisers and were able to purchase land on High Street and build their first church building in 1819.

By the middle of the 19th century, Brooklyn saw the establishment of many more African Methodist churches, making the AME the largest Black Protestant denomination in the city. The Methodists belonged to a larger oversight authority, but Baptists had no such hierarchy. Anyone could put together a congregation and call themselves a Baptist church and many did, almost matching the Methodists in number. As the Civil War loomed, Black Presbyterian, Episcopalian, and Congregational churches were founded. Black Catholics didn’t organize until much later, joined by Black Jews and Muslims.

Slavery was officially outlawed in New York in 1827, the last northern state, save New Jersey, to do so. But that didn’t mean African Americans in Brooklyn enjoyed equal rights in society. Brooklyn’s schools did not admit Black pupils, many adults could not read and were unable to enroll in higher education, and most positions available were unskilled and low paying service jobs. There was also the issue of continued slavery in the South. The churches saw their mission as more than just worship; they saw the opportunity for meaningful action. The fight for freedom for all was crucial to their credo and their existence.

Because Brooklyn’s African American community was concentrated in the Downtown Brooklyn and Dumbo area until the 20th century, the earliest churches have names that reflect the streets in that neighborhood: Concord Baptist Church of Christ, Fleet Street AME Zion, and Bridge Street AWME churches, specifically. They, along with Downtown’s Siloam Presbyterian and the Berean Baptist Church in Weeksville, form the core of our story.

The church grows

After building their first church on High Street so the congregation could finally take part in all aspects of worship and church life, the AWME set some more secular goals. Church members and brothers Peter and Benjamin Croger owned a whitewashing (house painting) business. They established the first African School in Peter’s home in 1818, teaching both children and adults. In 1827, they and Trustee Henry C. Thompson established the African Free School, located in Wallabout. It later became part of the Brooklyn school system and was called Colored School No. 1. It existed until the late 1800s when it was absorbed into an integrated public school system.

The church continued to add new members and eventually needed more room. In 1854 they purchased the First Congregational Church building, located at 309 Bridge Street. Sometime afterward, they changed their name to the Bridge Street AWME Church. This red brick Greek Revival building, built in the late 1840s and now a part of the Metrotech and NYU-Tandon School complex, is the only downtown Black church building remaining from this mid-19th century period. Today, it’s the Wunsch Building and houses the college’s undergraduate admissions office.

The success of both Black and white abolitionists and the Underground Railroad in helping those in bondage seek freedom in the north and Canada was the impetus for the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. This federal law allowed Southern slave catchers and their employers to come north and capture escapees. Bridge Street AWME was a station on the railroad, sheltering and aiding fugitives to safety in Canada. The church sponsored abolitionist speakers such as Harriet Tubman, raised money, disseminated literature, and did everything possible for a cause that was technically illegal. After the war, they continued to work toward equality for Black Americans in Brooklyn and beyond.

By the late 1930s, Brooklyn’s African American community began leaving the downtown area for central Brooklyn, steered there by redlining practices and the destruction of Downtown Brooklyn to make way for highways and new construction. Many of Bedford Stuyvesant’s established white churches sold their buildings to African American congregations and left central Brooklyn, following their flocks to other neighborhoods. In 1938, Bridge Street AWME moved to 277 Stuyvesant Avenue in Stuyvesant Heights after purchasing the former Grace Presbyterian Church.

Members branch out

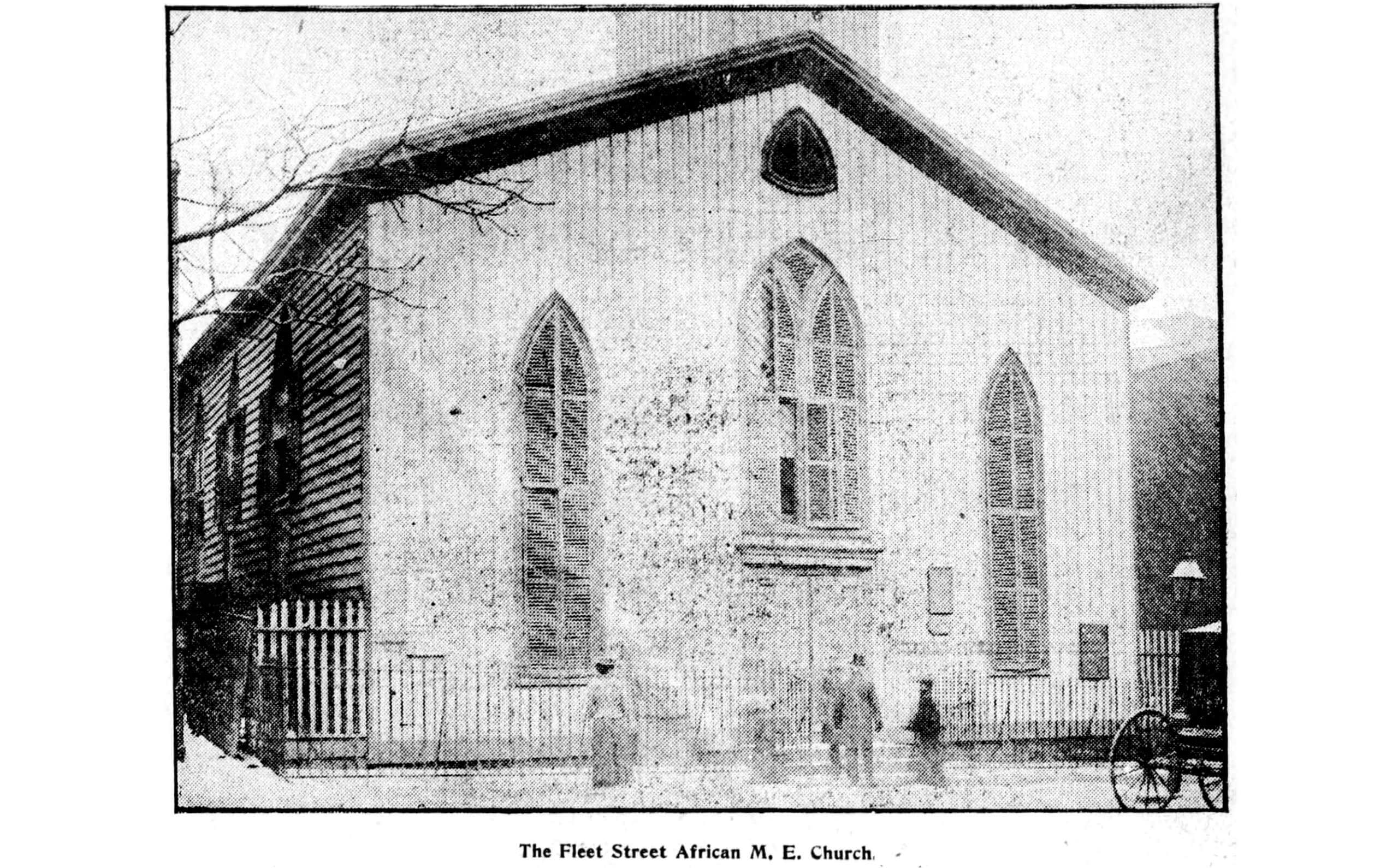

The Fleet Street AME Zion Church was founded in 1885 by a group of Bridge Street AWME members who split off from that institution. The new congregation purchased the former Fleet Street Methodist Episcopal Church building, a wood-frame structure once located where the entrance and exit ramps to the Manhattan Bridge now run. The church grew in numbers and was one of the more important Black churches in the downtown area.

The church building was one of the oldest structures in the neighborhood and was in deteriorating shape. In 1905, a funeral for a popular band leader named Sidney Painter caused a tragedy. There were too many people crowded into the building, and it collapsed in on itself, causing multiple fatalities. Many more would have died had the stairwells not held long enough for people to escape. The church had to relocate to a Bridge Street building, during which time they changed their name to First AME Zion Church.

In 1942, with the largest African Methodist congregation in the city, the church purchased the former Tompkins Avenue Congregational Church, a large church complex on the corner of Tompkins Avenue and MacDonough Street in Bedford Stuyvesant. They continue to be a strong presence in the African American community, with a food pantry and other social programs.

Commute-weary Baptists

For many years in the middle decades of the 19th century, Brooklyn’s Black Baptists had to take the ferry to Manhattan to worship at Abyssinian Baptist Church, Manhattan’s oldest African American congregation, then located on Worth Street. It was too much for many, so the Brooklynites began meeting in member’s homes. In 1847, they decided to establish their own church in Brooklyn. Funds were raised, enabling them to hire a former Abyssinian minister, purchase land on Concord Street near Duffield Street and build a church. The new Concord Baptist Church of Christ was soon ministering to a growing group of Black Baptists.

Like Bridge Street AWME, Concord was very active in the abolitionist movement, and was also a station on the Underground Railroad. Their second pastor, Reverend Leonard Black, had need of that escape route himself, as he was also a fugitive, and with slave catchers on his trail had to travel on the Underground Railroad to safety in Canada.

Concord continued to be led by activist ministers throughout its history. In 1939, Concord moved to Bedford Stuyvesant, purchasing the former Marcy Avenue Baptist Church on Marcy Avenue between Madison Street and Putnam Avenue. It was now the second largest Baptist church in the country, led by the Reverend Gardner C. Taylor, a giant in Brooklyn’s Black church history who was a civil rights champion and a great orator. His sermons appear in divinity school textbooks to this day.

In 1952, a devastating fire destroyed the building. The congregation began fundraising immediately, and two years later the new church was christened. Keeping in the tradition of community uplift, Reverend Taylor and church members began a successful credit union, an elementary school, and a senior citizens home, all clustered around the new church building and all of which are still in operation.

Activists shape Siloam

Siloam Presbyterian Church was founded in 1849 with the Reverend James Gloucester, formerly of Philadelphia, as pastor. Their first permanent church building was downtown on Prince Street, two blocks from First AME Zion Church. The pastor’s wife, Elizabeth Gloucester, was an extremely successful entrepreneur and the owner of Remsen House, an upscale boarding house in Brooklyn Heights. Both Gloucesters, as well as the congregation, were very active in the cause of emancipation, sheltering fugitives and aiding them along the Underground Railroad. They were also firm supporters of John Brown and his cause.

Letters between Brown and Gloucester have been preserved. When Brown stopped in Brooklyn before heading to Harper’s Ferry, he spoke at the church and stayed with the Gloucesters. After the war, the church was active in improving civil rights for African Americans, organizing a Literary Union to promote literacy and the hiring of Black school teachers, and other self-help initiatives.

Siloam moved several times in the 20th century before landing in Bed Stuy in 1944, where they purchased the Central Presbyterian Church building on the corner of Jefferson and Marcy avenues. This 1936 Colonial Revival structure had replaced an older building destroyed by fire on the same site. The Reverend Milton Galamison, who became pastor in 1948, led the church and community in fights against housing and school segregation, staging the first successful citywide boycott of the New York City public schools in 1964.

Integrated from the get-go

An important African American Brooklyn church, Berean Missionary Baptist Church, is the only one not originally downtown. It’s located in Weeksville, the independent Black town founded in 1838 and named for longshoreman James Weeks. While most of Brooklyn’s churches were firmly segregated, Berean Baptist was organized by abolitionists as a fully integrated church, joining our other churches as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

By the 1880s, the white members had moved on, founding another church nearby, leaving the Black members in a too-small, aging wood-frame building. They began a fundraising campaign and purchased some land on Bergen Street between Utica and Rochester avenues. Architect Benjamin Wright was chosen and the church was built by both members and professional builders, making it the first church in Brooklyn to be built from the foundation up by African Americans.

Over the 20th and 21st centuries, it expanded in size as well as in social programs and is one of the most influential Black churches in the city. It has programs for youth services, crime prevention, health services, and a food bank.

Brooklyn’s Black churches are the foundation upon which the Black community rests. They provide not only places to worship and socialize but uphold a 200-year-plus tradition of service to a people often discriminated against, marginalized, or ignored. The churches of all denominations are the glue that held Central Brooklyn together through redlining, drug wars, poverty, and disinvestment. Although the membership of all churches throughout the country are declining, the African American church community can still proclaim with pride that “we’ve come this far by faith.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2022 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- The Hiram S. Thomas Story: Brownstones, Potato Chips, Black Excellence in 19th Century Brooklyn

- The Tale of a Pioneering African-American Father and Son: Rufus L. Perry Sr. and Jr.

- The Weeksville Heritage Center Looks to the Future With a Focus on Art and Community

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment