The Hiram S. Thomas Story: Brownstones, Potato Chips, Black Excellence in 19th Century Brooklyn

College educated and from Canada, Black hotelier Hiram S. Thomas was a self-made success and master of the art of fine and gracious dining in 19th century America.

Clockwise from lower left: The Grand Union Hotel dining room in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Photo via Library of Congress. Grave of Hiram S. Thomas by Susan De Vries. Hiram S. Thomas in an undated portrait. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. 131 Fort Greene Place by Susan De Vries

The full-service restaurant and dining out for pleasure is a 19th century invention, born of the pre-Civil War urban experience and the rise of cities. It didn’t take long for this kind of experience to be replicated not only in places like Gage & Tollner and Peter Luger in Brooklyn but in cities and resorts across the country.

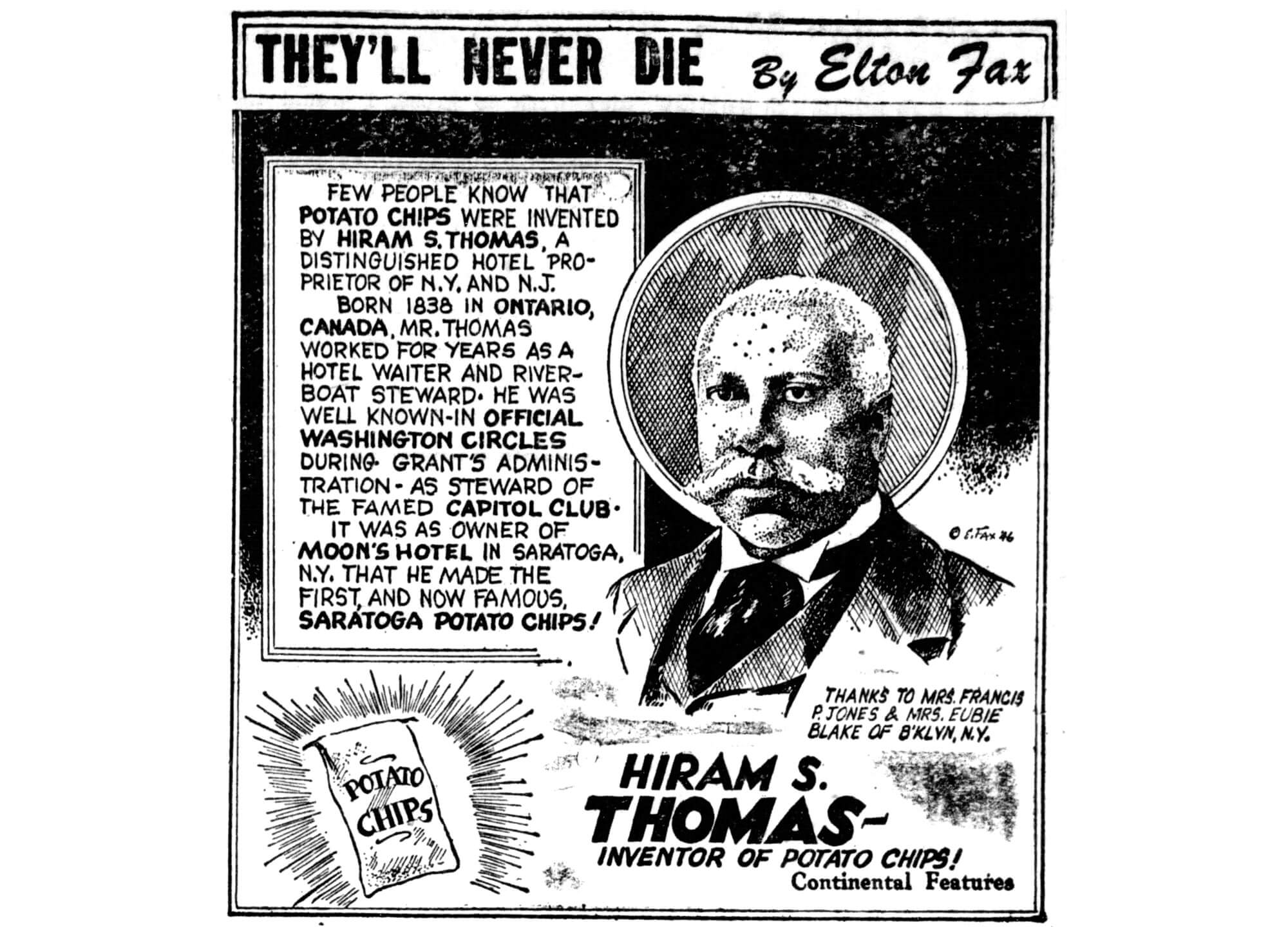

Into our story comes Hiram S. Thomas. Niagara Falls in Ontario, Canada, was still called Drummondville when he was born there in 1837. His family’s history in the area is unknown. Thomas was college educated, but opportunities for Black men with a college education were few in mid-19th century North America. He spent his early working years as a waiter and steward on passenger boats plying the Great Lakes and the Mississippi.

By the 1870s, during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, Thomas held the position of steward at the prestigious Capitol Club, in Washington, D.C. Many fine dining establishments of the day were staffed exclusively by Black waiters, a trend that continued into the 20th century in some places, including at Gage & Tollner. Thomas was described as tall, elegant and refined, and his job as steward allowed him to interact with presidents and kings.

Everyone writing about Thomas describes him as well spoken, witty and engaging. He was a favorite of President Grant and, later, of presidents Cleveland and McKinley. He chatted with other prominent politicians and saw to the culinary needs of heads of industry and commerce, all patrons at the club. He was able to make a good living, much more than most Black men of his time. He married, and he and his wife, Julia, would eventually have eight children: five daughters and three sons.

He left the Capitol Club and moved with his family to Saratoga Springs, the New York resort town north of Albany famous for its mineral springs, horse racing, gambling and luxury hotels. Anyone who was anyone came north, out of the city, for “the Season.” Many stayed at the Grand Union Hotel, which by 1876 could accommodate 2,000 guests and was billed as the largest hotel in the world. At that time, it was owned by A.T. Stewart, the ultra-wealthy owner of Manhattan’s largest department store of the same name.

Hiram Thomas was hired as the hotel’s head waiter. An 1878 article in the St. Louis Globe (syndicated from the New York Herald) describes the scene at dinner on a typical night at the Grand Union. His staff, many of them veterans of colored Union Army regiments, stood at attention at the doorways.

“At 2 p.m. 200 colored waiters stand spotless in an orderly array. The far-famed Hiram S. Thomas, a man of gigantic but graceful frame, is their generalissimo. His captains-general, attired like himself in full evening suits of black, are stationed at equal distances apart down the center aisle. The lieutenants stand along the sides. Every table is attended, according to its size, with two to four waiters, and every waiter is watched by the assistance of the generalissimo…Watch the generalissimo! With what intuition he comprehends the disposition and wish of each hungry guest. Always polite and accommodating, never hurried, yet performing his task with a celerity that saves everyone from waiting, this potentate of the dining room is an artist.”

Thomas did well here, and as his fame and reputation grew, so did his bank account and ambitions. In 1888, he took over the running of an upscale resort hotel on Saratoga Lake called Moon’s, and brought his now-famous class and elegance to what he renamed the Lake House. In the beginning he owned only the restaurant; later he bought the entire establishment. The hotel was mentioned often in New York’s society pages, and Thomas referred to as the well-known and respected colored man who owned it.

The Lake House was most famous for its food. In the summer of 1888, one of its chefs was Emeline Jones, declared by her wealthy clientele to be the “best cook in America.” Mrs. Jones was so admired, she had been wooed by both Presidents Cleveland and Arthur to come to the White House, but she declined. She went to Washington to cook one meal for President Arthur and then came back to Saratoga to work for fellow African American Thomas.

Another African American chef at the Lake House also made culinary history. His name was George Crum. Local lore has it that he prepared some sliced potatoes for a guest. The guest sent them back, saying they weren’t sliced thinly enough. He sliced the potatoes thinner, but they were again rejected. Frustrated, he sliced the potatoes paper thin, deep fried them, put plenty of salt on them, and sent them out one more time. The guest was elated. Soon everyone at the Lake House wanted the new “Saratoga Chips.” The potato chip was born.

Many years later, Thomas’ granddaughter, Marion Tyler Gant, told the African American press that her grandfather had invented the potato chip. It was the topic of much publicity and pride, especially since Ms. Gant was married to famed composer Eubie Blake. Their brownstone at Bed Stuy’s 284A Stuyvesant Avenue was passed down to her from Thomas. But today, most culinary historians give George Crum the credit. That’s fine, because Hiram Thomas had quite the reputation on his own merits.

In 1892, a New York Times writer vacationing at Lakewood on the Jersey Shore, where Thomas was working in the off season, wrote, “Who should be the headwaiter, but the dignified and portly Hiram Thomas, from the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga, who has ‘head-waitered’ upon me many times in that establishment; and Mr. Thomas stood by me while I ate the Lakewood’s Little Neck clams…..It is no small honor, you must understand, to have the dignified headwaiter in a big hotel devote his time to you and even stop to talk with you. But I wore my laurels as modestly as I could.”

In the summer of 1884, Thomas was working the room at his Lake House. He stopped to chat with General Edward Molineaux, whom he knew from his Capitol Club days in Washington. The general had been a member of General Grant’s staff during the war and during the Grant presidency was a frequent guest at the club. In the course of conversation, Molineaux dropped that he now lived in Brooklyn. Thomas was elated. Perhaps the general could tell him about a property that Thomas had just purchased for himself and his family? Most of his children were of college age or older, he was thinking about retiring at some point, and this new house would be a homey respite from his busy summer schedule. Brooklyn was also the halfway point between Saratoga and New Jersey.

Molineaux explained that he might not know the neighborhood that Thomas’ new home was in, after all — but he lived at 117 Fort Greene Place, a quiet street not far from Washington Park and Downtown Brooklyn. His brother-in-law, whom Thomas also knew, lived on the block as well. What a splendid coincidence! Thomas had recently purchased a home on the same block, at No. 131 Fort Greene Place, he told Molineaux. The general and the generalissimo would be neighbors.

The general rushed to tell his sister in Brooklyn the news. She and her husband, retailer J.S. Burnham, would be living next door to the Thomas family! Burnham shared that news with his landlady, Dr. Emma Onderdonk, one of Brooklyn’s first female physicians. She was horrified at the thought of a Negro family moving onto the block, even one so distinguished as that of Hiram S. Thomas. Soon word of the sale spread to every house on Fort Greene Place.

Dr. Onderdonk organized a committee to stop the sale. The group met in her house for a series of strategy sessions. Her first move was to attempt to sue the seller, Dr. Harry Smith. He had already moved to a new home in Prospect Heights and had put the sale of the red brick and brownstone townhouse in the hands of his realtor, Thomas J. Henderson. Smith was on record saying he really didn’t care who bought his house, as long as the parties had the money to buy it. Henderson is quoted by the Eagle as saying that he would not mind living next door to a Negro, in fact, would prefer one as a neighbor to some white people he could name.

Naturally, the press had a field day with the story. The headline in the Eagle on October 1, 1894 read, “Flurry in Ft. Greene Place, Because a Negro Has Bought a Three Story House. Aristocratic Neighbors in a Panic.” The Times headline read, “They Want No Colored Neighbor.” As the story progressed, it was picked up in syndication by newspapers across the country. The story of who Thomas was, the location of the house, the neighbors, all became fodder for many papers.

Not everyone in Brooklyn was up in arms. Some people were downright embarrassed and angry. Many of the residents on the block said they had no problem with Thomas and his family moving in. Rev. S. B. Halliday, assistant pastor of Plymouth Church, wrote a scathing letter to the Times. In part, he said, “I have supposed that the residents of Fort Greene Place were so eminently respectable that they could not have feared that their respectability could ever be called in question by the coming of half a dozen respectable families of color settling around them, much less by a single family. What a pretty story it is to get abroad over the country that a black man cannot move into a respectable neighborhood without stirring up a rebellion….I think our city is disgraced by the presence of such a spirit in its midst.”

Meanwhile, the Molineaux extended family and Dr. Onderdonk continued their efforts to dissuade Thomas from moving in. But that only fueled the negative rumors that Thomas was a greedy speculator out to scare the white folks into buying him out for big bucks.

When this was passed on to Dr. Onderdonk, she told the newspapers, “If he [Thomas] is a respectable good man, as they say, he will not wish to live there after this trouble. If he does move in, values will all become depreciated and he will lose as much as anyone else.” She also went on to say that if they couldn’t stop Thomas from buying the house, he ought to at least have the decency to not reside at the property.

Hiram and his family ignored the racism. As speculation as to his motives and future actions spread around the neighborhood, he went on with his moving plans. On October 3, 1894, an article in a tabloid called the New York World announced that the residents of Fort Greene Place were jubilant that morning because they heard that the Thomas family was not moving in.

The day before, the paper reported, neighbors could be seen peering from their windows, waiting in dread for the moving van to pull up to No. 131. Had Thomas moved in, some neighbors declared, they would be moving out. At once. But they had heard from General Molineaux that Thomas would not move in. “The matter has been settled,” Mrs. Molineaux told the reporter. Or had it? Thomas was of a different opinion.

The next day, the Brooklyn Eagle posted an article with an interview with Thomas, who was still up in Saratoga Springs. He denied buying the house as a speculation. He also revealed that he had considered both Molineaux and Burnham to be personal friends of his. Burnham had even written to Thomas entreating him to take special care of his brother-in-law while he was up in Saratoga. He was shocked at the amount of vitriol over his purchase of the house next door to Mr. Burnham.

He also related that the general tried to buy him out. Thomas told him that he would sell, but he was going to capitalize on his investment, and sell for a higher price than what he purchased the house for. “If my coming into the neighborhood will depreciate property, as some have said it would, I am willing to sell my house. But I don’t think I should be put in all this trouble for nothing.” Molineaux couldn’t afford the house, and the ad hoc Brooklyn committee didn’t have the funds, either.

“I have ordered carpets and furniture, which are now being placed in the house,” Thomas told the reporter. “My family will occupy it in ten days. We will reside there until I go to Lakewood on the first of December.” True to his timeline, by late October of 1894, Charles O. Thomas, the eldest son, was seen at the house. During the day, grocer’s and butcher’s wagons were seen making deliveries. Charles, two of his sisters, and two servants were now in residence.

Charles told reporters that no one had shown any hostility. “Because we live here is no reason why our neighbors should be compelled to associate with us,” he said. The Brooklyn Eagle announced on October 23 that Mr. and Mrs. Thomas had joined their children. No neighbors moved out, and nothing happened. Not with the Thomas family anyway. The next time reporters gathered on Fort Greene Place, it was because of General Molineaux. His son Roland was accused of being one of the early 20th century’s most notorious murderers. Perhaps they should have worried about him.

Thomas owned the Lake House for 10 years. He never retired. After giving that up, he took possession of the Rumsen Inn, in Red Bank, N.J., which he owned for 11 years. He didn’t live on Fort Greene Place for very long but did invest in other property in Brooklyn. When he died at his home in Red Bank after a long illness on July 8, 1907, he was 70 years old. One of his sons and two of his daughters had taken over his business, showing much of the same talent for hospitality as their father.

His funeral took place at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan, where he was a vestryman, and he is buried in the family plot in Cypress Hills Cemetery. Thomas was eulogized in papers across the nation. “One of the best-known hotel men in the country,” one paper announced. “The fine art of entertaining was his in largest measure.” Another paper stated: “He enjoyed a wide acquaintance among public men, especially those high in political and financial circles. General Grant was a warm supporter of his.”

Today, as the accomplishments of many of America’s unsung chefs, cooks and hoteliers of African descent are finally becoming better known, perhaps Hiram S. Thomas will become a household name once again — revered as his own self-made success, and a master of the art of fine and gracious dining.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- A Brownstone for a Remarkable Woman, Brookyn’s Pioneering Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward

- The Tale of a Pioneering African-American Father and Son: Rufus L. Perry Sr. and Jr.

- The Weeksville Heritage Center Looks to the Future With a Focus on Art and Community

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

you got every info wrong cuz i am a relative of george crum!!!!!!!! You are stupid he was born 2 hours ago?