Our Beautiful Brooklyn Blocks

From architecture to window boxes, a 19th century movement to beautify the streetscape in Brooklyn has left its mark on the borough.

Photo by Susan De Vries

A 19th century movement known as City Beautiful has had a lasting influence on Brooklyn and continues to shape the borough. The story of the effort to beautify the Brooklyn streetscape starts with well-known American architect Richard Morris Hunt, the Municipal Art Society, and a Brooklyn Heights artist named Zella Milhau.

The Municipal Art Society was founded in 1893 by Hunt, who in 1846 became the first American architect to be admitted to the famed École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Hunt, who was one of the finest architects of the late 19th century, is best known for his magnificent mansions that helped define the Gilded Age.

The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, and Biltmore, the Vanderbilt mega-mansion in Asheville, North Carolina, may be the most famous, but he had quite an influence on the architecture of New York City as well. Hunt designed the main entry hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. His classically inspired castles for the city’s richest people once lined 5th Avenue. He also designed hospitals, libraries, churches, and other buildings, including the now-demolished NY Tribune building, one of the first elevator skyscrapers.

Hunt made his fortune and reputation creating over-the-top opulence, but his greatest contribution to architecture was his championship of the profession and the art of creating the built environment. Before him, most Americans considered architects to be little more than jumped-up builders and carpenters, the kind of tradesmen who had to enter in the back of the house, not through the front door. Hunt, with his artistry and talent, was one of the most influential voices for the profession of “architect” to be on equal footing with any other educated profession such as doctor or lawyer.

To that end, he established his own atelier in Greenwich Village, where he trained a new generation of American architects in the Paris traditions learned at the École. One of his prize students was George Post, whose designs can still be seen in Brooklyn today. The Williamsburgh Savings Bank in Williamsburg and the Center for Brooklyn History (formerly the Brooklyn Historical Society) building in Brooklyn Heights are his. In 1857 Hunt cofounded the organization that became the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and served as its third president.

He founded the Municipal Art Society as an organization that would promote public interest in the arts and guide the city in creating works that promoted preservation, beauty, and dignity. He was its first president. These goals were in line with the City Beautiful movement, which championed the creation of a beautiful and Beaux-Arts city that through its public buildings and institutions would inspire the masses. Buildings such as the Brooklyn Museum and the classical elements of Grand Army Plaza are examples of this, as was the original Penn Station, the Post Office, and Manhattan’s Municipal building.

The City and Block Beautiful

MAS was very interested in the aesthetics of the city. But creating beauty would take more than the efforts of government or even wealthy sponsors. The creation and longevity of the City Beautiful needed the participation of individuals on a neighborhood and block level. What better place to try this out than in the city’s “first suburb,” Brooklyn Heights?

The Brooklyn Eagle ran a full page spread on the topic on Sunday, February 9, 1902. The headline read, “The Municipal Art Society to Begin at Once the Task of Transforming Greater New York into a Beautiful City.” The page was illustrated with drawings of Manhattan sites that would be adorned with tall Greek and Roman-style columns, statuary, and fountains, and a rendering of Henry Street between Joralemon and State streets in the Heights. This would be the first “Block Beautiful.”

The Block Beautiful idea was the brainchild of artist Zella Milhau, who lived at 291 Henry Street. She was one of those fascinating people who appear for a time in history, disappear, and are rediscovered decades or even a century later. Her name was actually Zella de Milhau, and she was born in 1867 into what the snooty Brooklyn Life society page said was “a very aristocratic French ancestry, coming in a direct line from the Vicomtes de Milhau.” Her parents were successful owners of a pharmaceutical company.

There is some discrepancy as to where Millau grew up; the New York Times and the Brooklyn Eagle both declared that she grew up in the house on Henry and was from an old Brooklyn family that had “for generations occupied one of its quaint houses.” Her obituary stated that she was born in a house on Colonnade Row on Lafayette Street in Manhattan. Whatever her original home, she showed great artistic talent as a child and studied at the Art Students League of New York. In 1898 she moved to 291 Henry Street with her father and was immediately accepted into Brooklyn’s social register. She was already an active member of the Municipal Art Society and the Fine Arts Club of Manhattan.

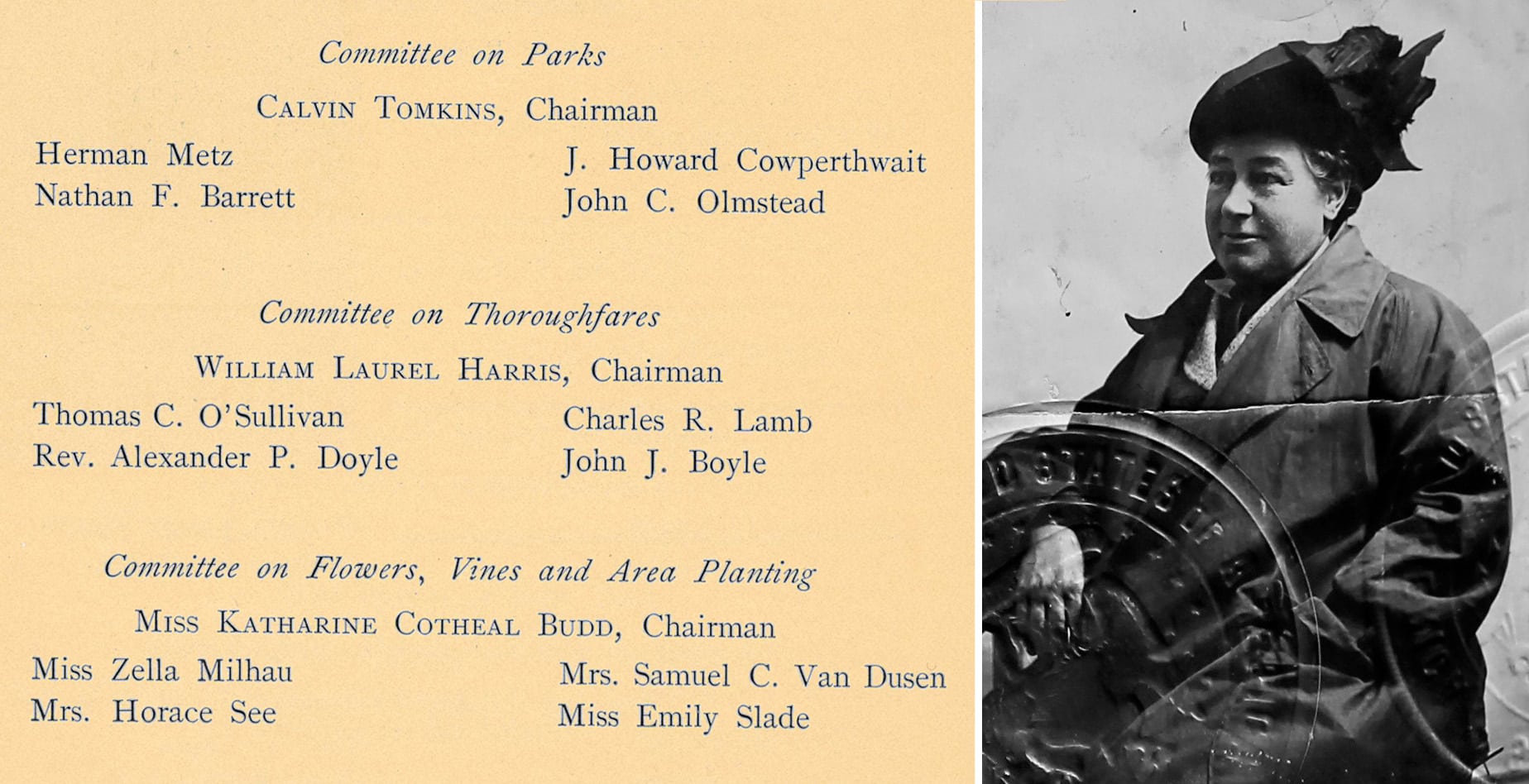

Recalling the streetscapes in many European cities, Milhau was inspired by “memories of the streets of some Continental cities where even the dingiest houses are given charm with flowering window boxes, climbing vines, shrubs in pots, all in full view of the street and small trees in front.” MAS had a Committee on Flowers, Vines, and Area Planting, chaired by Katherine C. Budd, one of the first successful female architects in America and one of the first women to graduate from École des Beaux-Arts, along with architect Julia Morgan. Brooklyn architect Fay Kellog, Morgan, and Budd were groundbreakers.

At first, the Block Beautiful was only going to include a few houses on that one block. Zella was put in charge of the operation and was a zealous project manager. After MAS distributed flyers and a few meetings were scheduled, many in the Heights were interested in being chosen. The Times reported that the block of Henry was populated by people from old moneyed families and modern-day financial success stories. “Well-known families,” the papers declared.

Four houses were ultimately chosen to start, including the Milhau house. Milhau advocated placing flower boxes in the windows and filling them to overflowing. She designed the boxes and had them made to her specifications. Some were zinc, which was the preferred material, while others had a row of decorative tiles across the front. Zella also made an arrangement with a select group of growers to supply everything needed. They placed planters in the front of the houses, and wherever possible, added greenery and flowers to the front yards. Meetings were held to determine the best plants to use, ones that gave homes the most color and quantity, and were hardy. Zella was very fond of ivy, vinca, and other vines that could spill over the boxes in a pleasing manner. Geraniums were hard to kill and were also favorites.

Before the end of the summer of 1902, flower boxes and planters were festooning the yards of 20 of the 48 householders on the block. Street trees were not very plentiful in the city at that time, and planting as many trees as possible was one of the goals of the program. Homeowners were encouraged to plant trees in front of their properties. Henry Snow, the president of Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, was an early advocate. Photographs of his house show a newly planted tree, lush flower boxes at the windows, and a planter at the top of the stairs.

Full-page articles complete with photographs or illustrations followed the progress of the program. The Brooklyn Heights houses were called “old fashioned” and “quaint” in many descriptions. The homes were prominently featured in the society pages of the papers. Some of the homeowners were eager to get their hands dirty and plant and maintain their greenery themselves, but Milhau knew others were not. Homeowners were advised to have the servants take care of the plants if the lady of the house didn’t do it herself. Milhau also arranged for the window boxes to be watered by a service for $3 a month; other landscape work cost an additional $1.25 an hour.

The Block Beautiful Expands

Homeowners in other parts of Brooklyn wanted in on the Block Beautiful. Quincy Street between Bedford and Nostrand avenues was an upscale block in a part of Brooklyn alternately referred to as Bedford or the “Upper Hill.” (Both Fort Greene and Clinton Hill were called “The Hill” by society wags.) This particular block had several freestanding and semi-detached mansions on it as well as rows of brownstones and contemporary wood-framed houses.

They instituted their own Block Beautiful program and invited Milhau to speak at a meeting where she explained her program and encouraged the group to follow the efforts in her neighborhood. Unlike in the Heights, every homeowner on the block signed up. Although Quincy Street didn’t have as much advance planning as Henry Street, they quickly rallied and purchased flower boxes and planters, plants, trees, and shrubs. Hanging baskets of flowers were also popular choices.

Ivy vines covering the facades of houses was a very popular look. Several homeowners already had ivy everywhere. It was thought to be very “cottage-y” and much admired by many. The papers published photographs of a home that had ivy covering everything except the windows and door. Today we realize that these vines with suckers holding them in place are damaging to the stone and brick, and harbor bugs and birds, but they didn’t know it then. Some houses today still have ivy covered walls.

The homeowners were all members of the Quincy Street Seventh Election District Association. They were quite a powerful group and were responsible for getting the street asphalted. The association planted trees in front of every house, with a total of 63 trees on the block, setting a record for the number of trees on any block in the city. One woman, Mrs. Manuel Gonzales, announced that she wasn’t going to wait for the group shipment of materials to arrive; she was going to “put every green thing she had outside,” and placed plants in pots on her steps.

The residents held a meeting of homeowners to discuss the problem of youthful vandals running through the street taking great delight in destroying everything they worked for. The group decided to ask the boys on the block to become block watchers and keep a lookout. They also wanted to organize the girls into a seed planter organization, but wanted to wait to see what the boys were able to accomplish. The block beautification was a huge success, although the Heights received much more media attention.

The Block Beautiful program continued the next year, with almost all of Brooklyn Heights taking part, according to Milhau. She penned an article published in a 1903 periodical called The World’s Work. In it she explained that when the notion was put forth, everyone thought it a grand idea, but no one wanted to be a pioneer. Many said that they would go in the next year because they wanted to see what their neighbors did first.

Milhau also laid out many of the problems incurred that first year. Finding the right kind of flower boxes that were to code (they had to be secured to the building) took time and trial and error. They learned that florists were not necessarily gardeners, being familiar with cut flowers and arranging greenery, not growing it. The right people had to be found. They also discovered that once participants arranged plants in the boxes, they had to be sure that they looked good from the street, not just their parlor windows. Many boxes had to be rearranged to achieve the best results. All in all, Milhau noted, they could fill a book called “What Not to Do.”

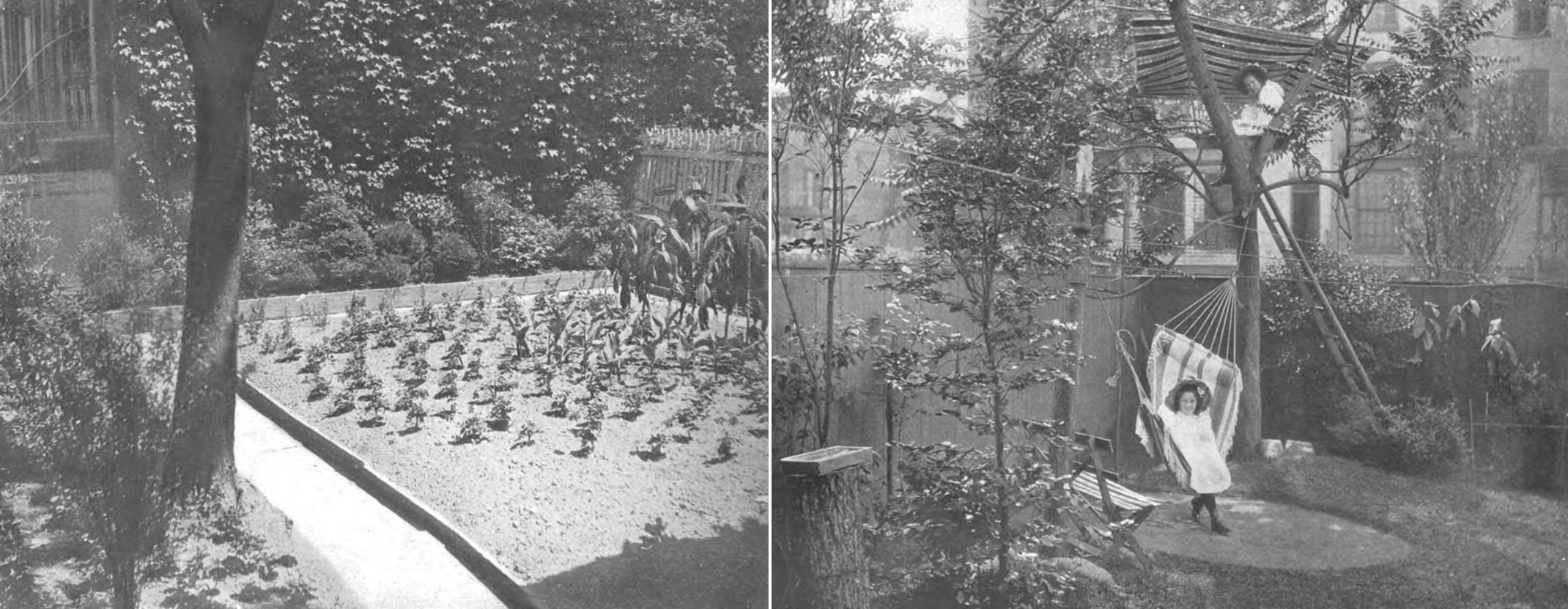

One aspect of Block Beautiful that was often overlooked was turning one’s backyard into a landscaped garden filled with flowers and shrubs. Milhau advocated taking back the rear yard from a space of packed dirt or stone and clotheslines visited only by servants. The yards could become private sanctuaries where a homeowner could relax. Her advice was accompanied by a photograph of a child in a backyard in a small hammock surrounded by trees and shrubs.

In 1904, Milhau moved to Southampton. She was very familiar with the area and had once attended the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art. She purchased one of the residences for college students there in 1896 and renamed it Laffalot. It became her home for the rest of her life.

And what a life! During World War 1, before the U.S. entered the war, Milhau traveled to England to serve with a volunteer motor corps. She was appointed a recruiting sergeant and worked to raise funds from her Southampton community. She raised enough to buy an ambulance in France, which she drove between the front lines and the field hospitals, a dangerous activity. After the war, the French awarded her the Croix de Guerre, the gold Medaille de la Reconnaissance Francaise and citations from three frontline hospitals and from the French town of Verberie.

Upon returning home, she bought a motorcycle and became Southampton’s first motor officer, chasing speeding motorists. The press found the “Society Girl Motor Cop” amusing, but she was serious. Milhau moved on from that position to policing duties as a parole officer and an interpreter for foreigners in court. All the while she was creating her artwork. She excelled in printmaking, and today her prints are in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smith College, and the National Gallery of Art in D.C. She died at the age of 84 in 1954.

From the Block Beautiful to the Greenest Block in Brooklyn

When the leader of a group leaves for whatever reason, the group can fall apart. Several years after Milhau moved to Long Island, the Brooklyn Heights ladies drifted away to new causes, and the official Block Beautiful committee was no more. But planting and maintaining greenery and flowers around houses caught on all over Brooklyn. One did not have to be rich to have a potted plant on the stairs or plant flowers in the front yard or rear garden. Although people stopped placing flower boxes on the top of entryway pediments, many continued the tradition of window boxes — especially those with deep sills.

The idea of the Block Beautiful persisted, carried on by various neighborhoods and blocks, and sometimes as a marketing tool for real estate brokers. Individuals were encouraged to continue to beautify their properties, which many did in all sections of the borough. In the 1990s, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden with the support of the Brooklyn Borough President Howard Golden initiated the “Greenest Block in Brooklyn” contest, which awarded one of the participating blocks the title of “Greenest Block in Brooklyn” for that year.

The initiative and contests have continued ever since. The contest is open to all residential blocks, commercial blocks, and community gardens. No longer restricted to one overall category, there are now prizes for the Greenest Block residential and commercial; the best tree beds, community gardens, and window boxes; and special awards. Recent winners have included entries from Stuyvesant Heights, Flatbush, Bay Ridge, Crown Heights North, Flatlands, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Park Slope, and more.

The Brooklyn Botanic Garden offers workshops, plant sales, and other programs for those who want to participate. An entire block on both sides of the street must participate. Each entry must be with a block association, civic, or ad hoc group. The contest is a wonderful way for an entire block to get to know each other and work together. The deadline to enter this year’s contest is June 1st, with judging in August.

Zella de Milhau started something that is now, 122 years later, much bigger and much more successful than she could ever imagined.

Related Stories

- ‘I Only Do Big Things’: Woman, Architect, and Brooklynite Fay Kellogg

- The Story of Brooklyn’s Lady Developers, Architects and Builders

- Rich With Tropical Plants, Flatbush’s East 25th Street Named Greenest Block in Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment