Crafting the Ideal: The City Beautiful Movement in Brooklyn

The movement was rather grandiosely designed to combat urban problems through architecture and city planning.

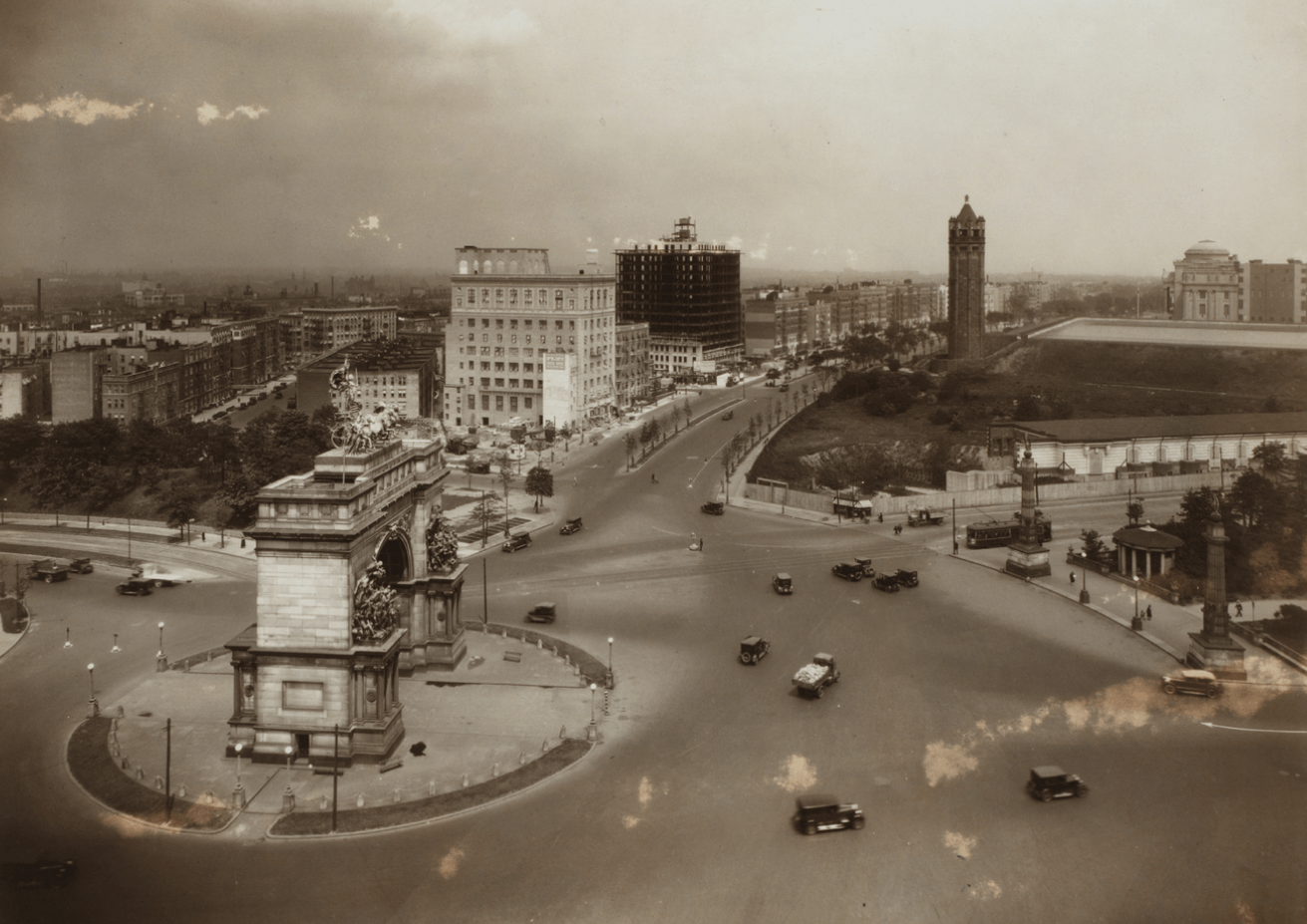

Grand Army Plaza circa 1901 to 1906. Photo by Detroit Publishing Co. via Library of Congress

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2009. Read the original here.

At the turn of the 20th century, reformers in American cities were aware that the great advances of industry and technology had both made tremendous wealth and advancement possible for many, along with the intensification of horrific poverty, and abominable living conditions for many more, as documented in NYC by Jacob Riis.

Civil unrest, strikes and riots persisted, and city fathers were getting worried, because the rich were leaving the central cities. The City Beautiful Movement was rather grandiosely designed to combat these problems through architecture and city planning.

The widely held social belief was that the poor were poor because they were morally and socially deficient, an attitude that lingers to this day.

It was thought that building a beautiful city would inspire all of its inhabitants to moral and civic virtue, and social ills would dissolve into pride and loyalty to this beautiful new city, thereby inspiring the poor to better themselves.

The City Beautiful would have parkland, where everyone could escape the streets to enjoy nature, this feature was especially important to one of the earliest proponents Frederick Law Olmsted.

The new classically inspired Beaux Arts architecture was also designed to show Europe that America had arrived, and was no longer a cultural backwash. And most importantly, the rich would then stop moving to the suburbs and stay in the central cities, and spend their money there.

The Movement had its largest success in the civic areas of newer cities like Denver, but its most impressive and lasting success was the transformation of Washington DC, spearheaded by Daniel Burnham, the architect in chief of the Columbian Exposition.

What we see today in central Washington, the Capitol area, the Mall, the lake and the monuments, is the White City, the City Beautiful, most fully realized. Tragically, the same social ills, supposedly banished, surround it, as well.

What about New York?

Manhattan was too busy, and in too much of a hurry, even at the turn of the century, for a full blown redesign to ever be done here. No reflecting pools for us.

The White City public ideal in NYC was best realized in McKim, Mead and White’s Municipal Building at 1 Centre Street, and the courthouses and civic buildings around it.

While every white or light colored limestone or brick building in New York was not specifically designed with the White City in mind, the Columbian Exhibition issued in a period where limestone and stucco replaced brownstone as the preferred building material.

Beaux Arts buildings, with their classical details became the style of choice for grand monumental civic and commercial buildings and the mansions of the rich.

There are many, many examples in Manhattan, from the Woolworth Building to the mostly vanished mansions of 5th Ave, to many of the fine office and manufacturing buildings in the Madison Square area.

We have to turn to Brooklyn for the further realization of the City Beautiful, especially in the growing communities at the turn of the 20th century, neighborhoods like Lefferts Manor, Crown Heights, and Park Slope, home to New York’s great monument to the ideals of the City Beautiful: Grand Army Plaza and Prospect Park.

The underlying philosophy of providing beautiful and free parkland for the people, as articulated by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvin Vaux, predates the City Beautiful movement, and Olmsted is credited as one of its originators, although he grew disillusioned as the movement progressed.

After the success of Central Park, the pair created their masterpiece in Prospect Park. The public plaza, including the Arch, predates the Columbian Exhibition by a couple of years, but they set the stage for the grander City Beautiful ideals of McKim, Mead and White, who were hired to crown the entrances to the Park with Classical aplomb.

In 1892 they proposed the grand statuary on and surrounding the Arch, as well as classical columns topped with eagles, as seen at the Plaza entrance, and they designed the other major entrances to the park. Surrounding the Park were block of new homes designed with the White City ideals in mind.

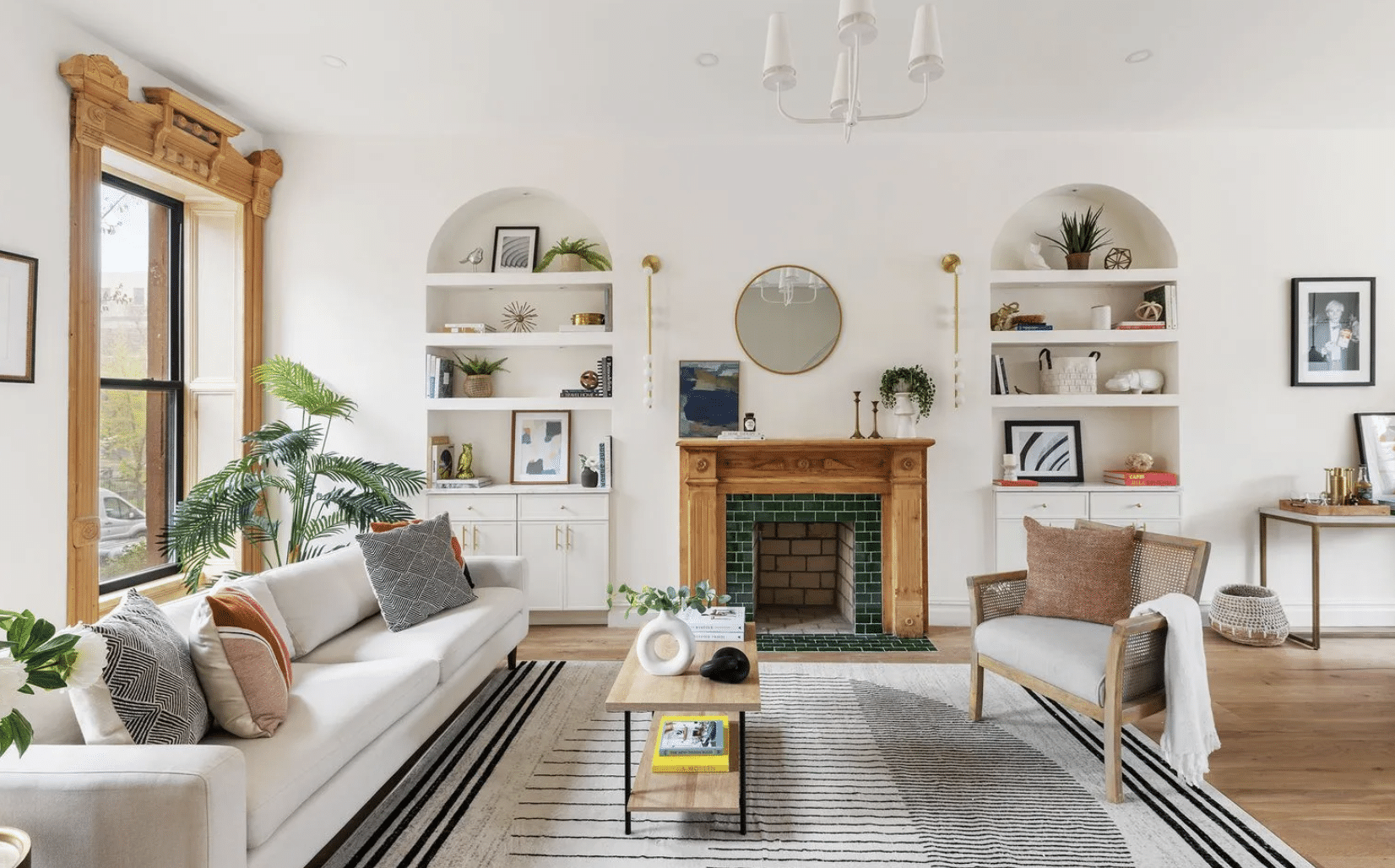

The single most prolific Brooklyn architect working with these ideals was Axel Hedman. His row houses in Park Slope, on and around the park, in Lefferts Manor, and Crown Heights, are beautiful rows of Renaissance Revival homes, faced in Indiana limestone.

Classical Greek and Roman details abound, along with Renaissance and Beaux Arts ornament such as cartouches, shields, foliate swags and scrollwork.

He is also responsible for an ornate series of tenement apartments facing each other on St. James Place in Clinton Hill, and similar buildings in Crown Heights North.

Other buildings, such as the Neo-Byzantine Church of Christ Scientist, in Crown Heights North, built by Henry Ives Cobb, in 1909, were specifically cited at the time as inspired by the White City Movement, and many more architects and builders went with the popular flow, and built in limestone and light brick.

The influences of the White City movement, the final true Victorian style, have added another layer to the rich mixture of architecture in our historic neighborhoods.

Related Stories

- The Grecian Folly of Prospect Park

- Walkabout with Montrose: World’s Fairs and White Cities

- The Gleaming Beaux Arts Boathouse of Prospect Park

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment