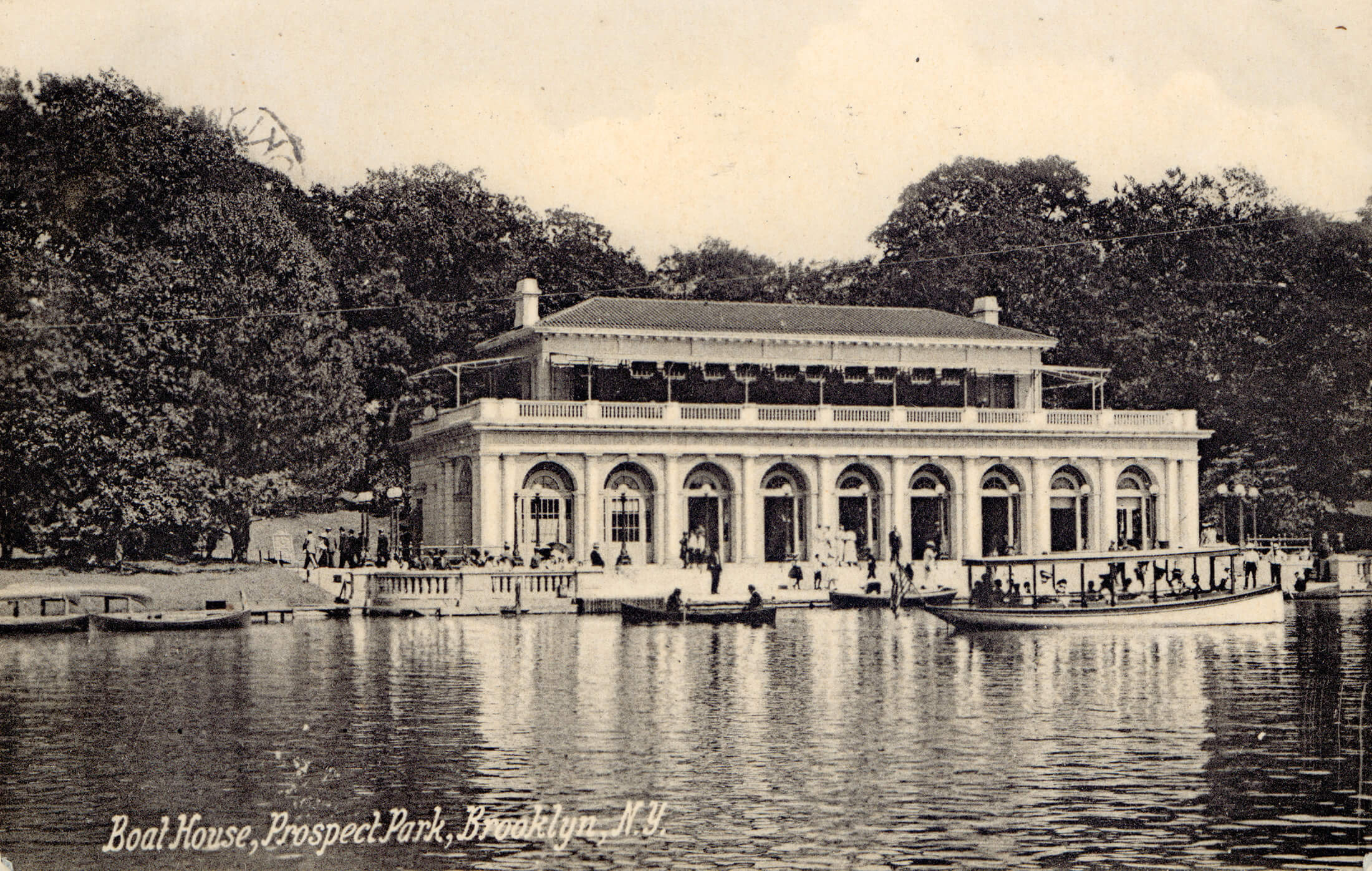

The Gleaming Beaux Arts Boathouse of Prospect Park

A definitive list of the 10 best buildings in Brooklyn would have to include the Prospect Park Boathouse.

2017 photo by Susan De Vries

Editor’s Note: This post originally ran in 2011 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

If I could ever decide on a definitive list of the 10 best buildings in Brooklyn, I’d have to find room for the Prospect Park Boathouse. It’s simply, and in the best sense of the word simply, magnificent. It also has a great history, and we are very lucky that it’s still here.

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed Prospect Park, they built man-made structures to enhance the natural beauty of the park, and provide places to congregate for events, or sit and enjoy the natural preserve. The first boathouse, built in 1876, sat on piers, and faced south.

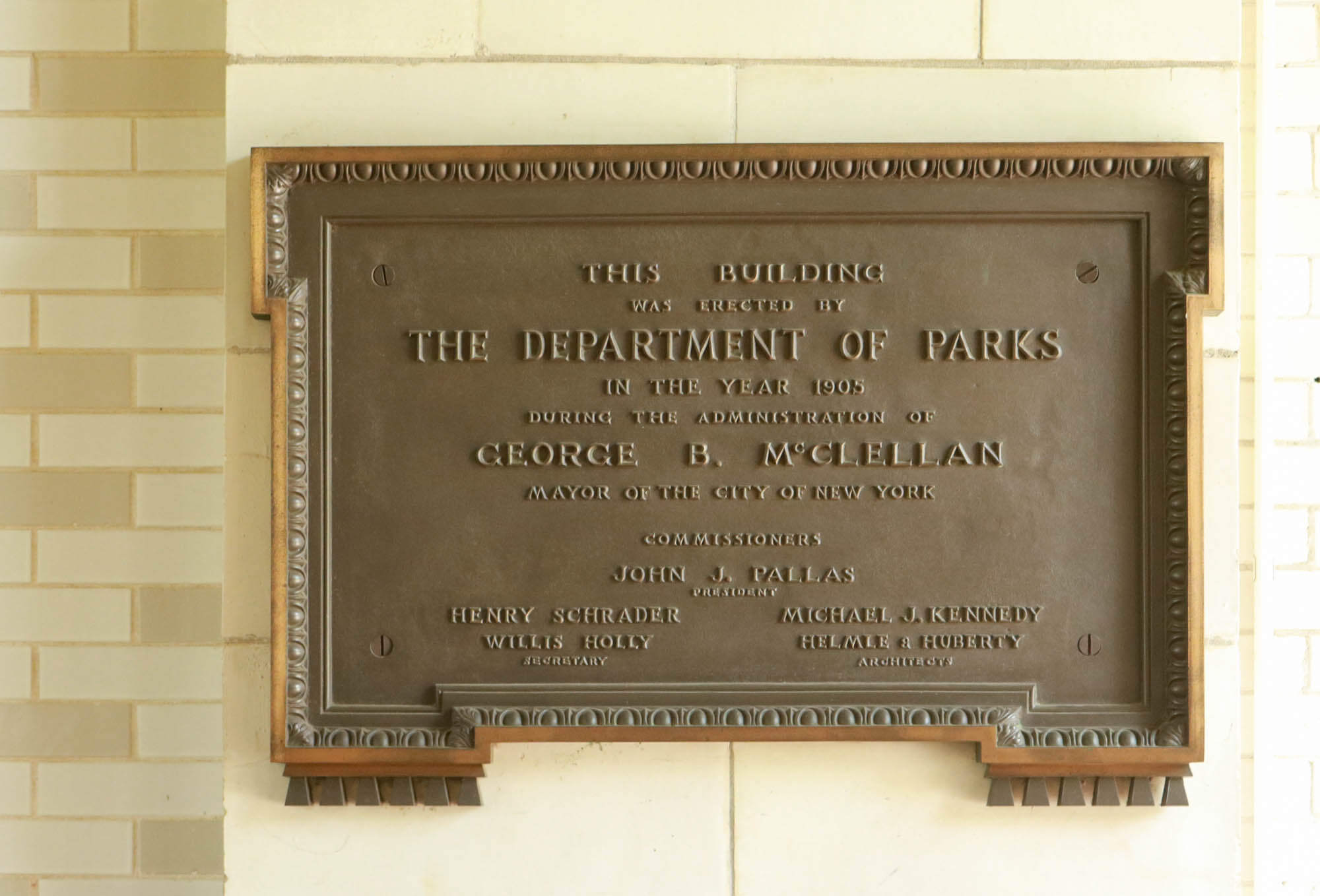

In 1905, this classically-inspired terra-cotta-encased building was designed to replace it. It faces west, by the way, purposefully to catch the sunsets over the water.

Frank Helmle and Ulrich Huberty were among Brooklyn’s finest architects, both producing excellent work, mostly in the White City, City Beautiful, Beaux Arts style of the early 20th century. Frank Helmle worked in the offices of McKim, Mead & White, who were masters of the style, where he obviously paid attention. He landed a lot of city contracts as Superintendent of Public Buildings in Brooklyn, a post he held from 1902 until at least 1913. This building was built during that time.

The partners based the design on the first floor of Jacopo Sansovino’s design for the Library of St. Mark, a Renaissance building in Venice. It is much simplified from the original, showing Helmle’s expertise at taking inspiration of the great buildings of the past, without slavishly copying them. His St. Gregory and St. Barbara churches are also a fine testament to his skill in that regard.

The building is clad in gleaming white terra-cotta, and positively glows in the sunlight.

Helmle & Huberty also took advantage of the Guastavino Company’s tile arch system. They had perfected the use of tiled vaulting and arches that were structurally perfect, lightweight and beautiful. Guastavino tile vaults can be found in many of the Beaux Arts buildings of the early 20th century, and Helmle used them on several occasions, as did his former employers at McKim, Mead & White. The boat house is Helmle’s best known example.

Historians have postulated that Olmsted and Vaux would have hated this building, as it is very reminiscent of the English folly tradition of putting classical temples in the landscapes of estates, and is not an organic structure, like their buildings and tunnels. Be that as it may, this remains one of the park’s most popular destinations.

We almost didn’t have it to love. During the 20th century, the boats were moved elsewhere, and the building was used for a number of purposes, was not maintained, was horribly rundown, a story repeated in all of our public parks’ histories. In 1964, the Parks Commissioner at the time, one Newbold Morris, said the building was toast, and needed to be torn down. Architectural historians cried nonsense.

Brooklyn poet Marianne Moore and other preservationists and concerned Brooklynites rallied to save the boathouse. They managed to do so literally 48 hours before it was scheduled to be torn down. The Landmarks Law was passed in 1966, and the boathouse was declared a city landmark in 1968, even before the park itself was landmarked in 1975. The boathouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

In 1971, the building received a new terra-cotta façade, but it was a botched job that used non-waterproof materials, and the building had to be closed in 1997 due to extensive water damage. In 1999, a $5 million dollar restoration was done to the entire building, in the process, creating the Audubon Nature Center, the first urban nature center of its kind. The restoration was designed by the Prospect Park Alliance Design and Construction team, including architect Ralph Carmosino, landscape architect Christian Zimmerman and construction supervisor Paul Daley. Well done, and thank you!

Today, the boat house is probably the most popular building in the park, and generates a lot of income for the park through private rentals for weddings and special occasions. Newbold Morris didn’t know what he was talking about, and thankfully, an active citizen protest and campaign showed the powers that be that it was worth saving. We now have this magnificent building with us today and for the foreseeable future.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- How Litchfield Villa, the Picturesque Mansion of Prospect Park, Came to Be (Photos)

- Boating About in Prospect Park (Photos)

- How Many People Did it Take to Plant a Tree in Prospect Park in 1867?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment