Walkabout: Brooklyn’s Architects: Stanford White, Part 6

In New York City, in the year 1906, Stanford White was America’s most famous architect. His firm’s buildings helped define the Gilded Age, a time of great wealth and excess, the dawn of the 20th century. A beautiful young model and actress named Evelyn Nesbit was America’s first famous pin-up girl, her image gracing the…

In New York City, in the year 1906, Stanford White was America’s most famous architect. His firm’s buildings helped define the Gilded Age, a time of great wealth and excess, the dawn of the 20th century. A beautiful young model and actress named Evelyn Nesbit was America’s first famous pin-up girl, her image gracing the covers of popular magazines, her likeness used in advertising all over the country. She was sought after by artists and photographers, and wooed by rich and famous men. One of those men was Stanford White; another was Harry Kendall Thaw, the heir to a Pittsburgh fortune. He was young, handsome, and as unstable as a case of nitroglycerin. Stanford White had issues of his own, and these three people, dubbed by an eager press, a doomed “love triangle,” would make history. It didn’t work out well for any of them. Here’s the conclusion of this famous story.

In April of 1905, Evelyn Nesbit was married to Harry Thaw in a private ceremony in Pittsburgh. Harry desperately wanted Evelyn Nesbit, and after wooing her, first anonymously as a backstage admirer, then as an ardent suitor, he charmed, cajoled, and mostly bought his way into her heart. At 16, she was already the mistress of Stanford White, who had also wooed her, spent a lot of money on her, and then raped her one night after drugging her champagne. She fell in love with him anyway, and was his mistress for over two years.

When she told Harry this, on a European trip that he arranged for the two of them, he came to her one night, in a remote castle room in Germany, beat her senseless with a dog whip, and also raped her, collapsing in a tearful heap after it was over, promising to make it up to her for the rest of her life. He also promised revenge on Stanford White for her desecration and ruin. For Evelyn Nesbit, her beauty and desirability had become her curse.

After becoming Mrs. Harry Thaw, Evelyn was stuck in Pittsburgh in the huge, gloomy mansion that was Casa Thaw. Her only company was her mother-in-law, who thought Evelyn was a little tramp, but because she was what Harry wanted, Mother would make sure Evelyn was safely under her thumb. When Harry expressed a desire to go to England for a vacation, with time spent in New York City before their ship sailed, Evelyn was overjoyed.

The couple came to the city where Harry announced that he had tickets to a show at Madison Square Garden, at the rooftop dinner theater that was the toast of the town. The show was called Mamzelle Champagne, a light hearted musical folly, the kind of show Evelyn would have been in, only a few years before. That night, as the couple had dinner with friends, Stanford White and his son Lawrence came into the same restaurant. Harry didn’t see them, but Evelyn did, afraid that Harry would make a scene. When Harry found out, he didn’t explode, just turned inward, seething with a rage that would cause him to put his hat on so angrily that he cracked the rim, ruining it.

Harry somehow found out that Stanford White had tickets to the same show. It was like destiny. Throughout the show Harry paced the back of the restaurant like a tiger in a cage. Evelyn was worried, but White was not there. As the show approached its last act, Stanford White entered the room, and took his customary seat at a table near the front. The last number was up, with dancing girls, the kind of entertainment Stanny loved. Evelyn and Harry saw White come in, and Harry stood up, with a glazed look on his face. Evelyn pulled him towards the door, but Harry broke away. Someone stopped Evelyn to speak to her, and Harry went back into the room.

Stanny was watching the girls, his last act on earth. Harry approached him from the back, pulled a gun, and shot White three times, at point blank range. Stanford White was dead, with two bullets in his head, and one in his arm. At first the audience was stunned. Some even thought it was a prank, as rich jokesters were prone to large displays of fakery and practical jokes. But the blood and White’s injuries were visible, and it was no joke. Harry didn’t even run. He stood there shouting, “I did it because he ruined my wife. He had it coming to him. He took advantage of the girl and then deserted her.” As the police pulled him from the room, he told a tearful Evelyn, “It’s all right, my dear, I’ve probably saved your life.”

Harry spent the night in the infamous Tombs prison, charged with murder. While speculations raged as to the motive and the players, the Edison studios rushed through a quickie film called “The Rooftop Murders” for distribution at nickelodeons. The feeding frenzy was on. Next would be the “Trial of the Century.”

The DA’s office wanted to end it quickly, by declaring Harry Thaw insane, sending him to an asylum, and tossing away the key. Thaw’s original attorney agreed, also eager to end the whole affair. But Harry and his mother thought otherwise. He fired the lawyer he called “The Traitor,” and hired another who would take the stance that Harry was protecting his wife from sexual perverts like Stanford White, who preyed upon innocent young girls, and deserved to die.

In January of 1907, a jury pool of six hundred men was whittled down to twelve. The defense strategy proposed by Harry’s new lawyers, and his mother, was that Harry had had an attack of “temporary insanity,” something any upright man would have had he learned of his wife’s history and disgrace. The DA’s office had a simpler motive: cold blooded jealousy and revenge. Opening statements fleshed out those theories on both sides. The audience, and the attending press, and therefore the nation, were mesmerized.

When the defense was give their chance to make their case, a new lawyer was brought in, Delphin Delmas, of San Francisco, who had never lost a case. His plan was simple, and pleased Harry very much. Instead of trying to excuse Harry’s actions as the act of an insane man, they would attack Stanford White. He would be portrayed in the worst way possible; as a sexual predator, the spoiler of young women, and a hedonistic pervert.

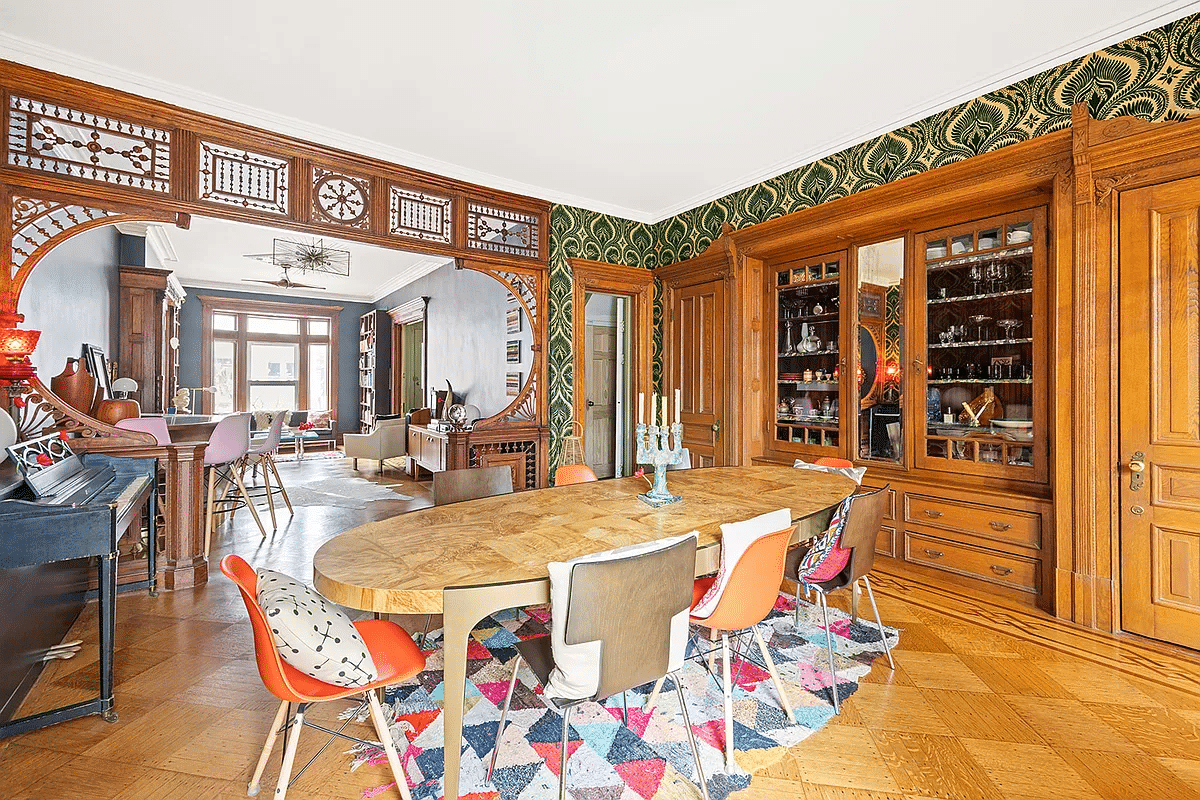

It all came out, White’s reputation as a profligate sexual “satyr,” the apartment with the red velvet swing and the wall of mirrors, the parties, including a particularly infamous one where a nearly naked 15 year old girl popped out of a pie dressed as a bird. Stanny had sex with her that night, too. There were White’s many affairs with other young ladies, and most importantly, every detail of his deflowering and subsequent affair with Evelyn Nesbit. She was the star witness, and over the course of days, told everything, in tear-filled testimony that had the courtroom in tears and in a righteous fury. If Stanford White hadn’t have been dead, they would have killed him.

The District Attorney cross examined Evelyn, and tried to put some of the onus on her, insinuating that she had posed naked for artists for money, and asking he why she stayed in the affair with the much older, and very much married Stanford White. She denied ever posing nude, and admitted she had been wrong to have the affair, but she had been young, and Mr. White had always been so kind to her. She hadn’t realized how wrong the affair was until she had told Harry about it in Europe, and had been horrified and frightened at his reaction.

After Evelyn tearfully finished her testimony, the defense called doctors who testified that Harry was not responsible. Stanford White’s debauchery had unhinged him so much that he was sure White had agents out to get him, and that was why he had a gun. The sight of Stanford White had proved to be too much, and he had seen himself as an “avenging angel,” and the murder had not been planned, he was only going to bring White to justice, but “Providence” intervened.

The final witness for the defense was Mrs. Thaw, Harry’s mother, who testified that Harry had been devastated by Stanford White, whom she called “the worst man in New York.” White had ruined her son’s life, she said, leaving him sleepless at night, sobbing in despair. With that, the defense rested.

When the DA realized people were buying the defense’s story, he decided to hammer on the insanity of Harry Thaw. Evelyn was brought back to tell the sordid tale of her beating and rape at the hands of her then-fiancé. She testified about his morphine and cocaine addictions, his rages, and inability to control his temper in public and private. Others testified as to dangerous behavior over the years. Alienists, as psychologists were then called, were called upon to testify on Harry’s insanity, and danger to the public if he were to be exonerated. It was time for closing statements.

Delmas, Harry’s lawyer, made an impassioned and famous speech. He called Harry a victim of “Dementia Americana”, where any man would do what he needed to do to protect his wife, his property, or himself from harm; an insanity that any responsible American male, including the jury, would recognize. Harry had only been protecting his wife from a predator, nothing more. The DA, William Jerome, thought differently. He asked what kind of man would treat his fiancé the way Harry had, and then kill someone else who had at least treated her better. It was just jealous murder, nothing more. If every man suffered from “Dementia Americana,” then the country would be littered with bodies, and all men would have guns, looking for an excuse to use them. Harry Thaw was an insane, dangerous murderer.

The jury took the case, deliberated for 47 hours, and came back deadlocked. The trial was declared a mistrial. The second trial was very different. The defense, a different team of lawyers, dropped the “Dementia Americana” defense, and went with insanity. Everyone from Harry’s mother, through nursemaids, teachers and Evelyn, testified to his insane relatives, epileptic fits, childhood rages and tantrums, and adult drug use, suicide attempts and episodes of bad behavior. Harry was certifiable, they claimed, but not responsible for Stanford White’s murder. In the end, the jury agreed. Harry Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity. To his shock and horror, he was sent to an insane asylum for eight years.

So what happened to all of them? Harry was released in 1915, and divorced soon after. In 1917, he beat a boy nearly to death and was tossed back in the insane asylum, and was not released until 1924. He died in 1947, at the age of 76, known for his fits of rage and temper the rest of his life.

Evelyn was supposed to get a million dollar payoff from Mother Thaw to quietly go away. She had been pregnant, but Mother Thaw denied that the baby was Harry’s and didn’t give her a dime. Evelyn would remarry, and try to make a living in vaudeville and show business, but it had been her face and figure that launched her career, not her talent, and she barely made a living. She would succumb to addiction, alcohol, and poverty. She lived long enough to see Joan Collins play her in the movie, “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing.” Evelyn Nesbit Thaw died penniless in 1966 at the age of 81.

Stanford White’s reputation took a big hit. During the trial, the defense had made him out to be a horrible perverted predator, his sexual escapades made even worse by the press and the times they all lived in. Even his architectural reputation suffered, his buildings excoriated for their luxury and excess, and he had been scorned at the trial as a hack. For generations, his family tried to live down the infamy, and it has only been recently that his architectural achievements have once again superseded his personal life. Should we overlook his most definite serious faults, or only look at the beauty he created with his buildings and other structures? Or are both intertwined, and was Stanny White simply both immensely talented, and immensely flawed, a mere human being, writ large on the stage of human events?

(Photo of Stanford White: amyvermillion.com)

Walkabout: Stanford White, part 1

Walkabout: Stanford White, part 2

Walkabout: Stanford White, part 3

Walkabout: Stanford White, part 4

Walkabout: Stanford White, part 5

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment