Schrafft's Sweet Corner in Downtown Brooklyn

The well-appointed restaurants were very popular with working women as well as the ladies who lunched.

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2011. Read the original here.

Investigating the history of Brooklyn’s buildings can be like peeling back an onion. If a building is old enough, or in a commercial district where there is a lot of turn around, it can have a history that is absolutely amazing in complexity. Sometimes those layers of history are very visible somewhere on or in the building, and you may find yourself wondering, “What did that building look like when it was a (fill in the blank)?”

So it is with 386-388 Fulton Street, also known as 1 Smith Street, on the corner of Fulton Street and Smith Street, in Downtown Brooklyn. Now a Duane Reade, it was once home to one of the many restaurants/candy shops of the Schrafft’s Candy Company.

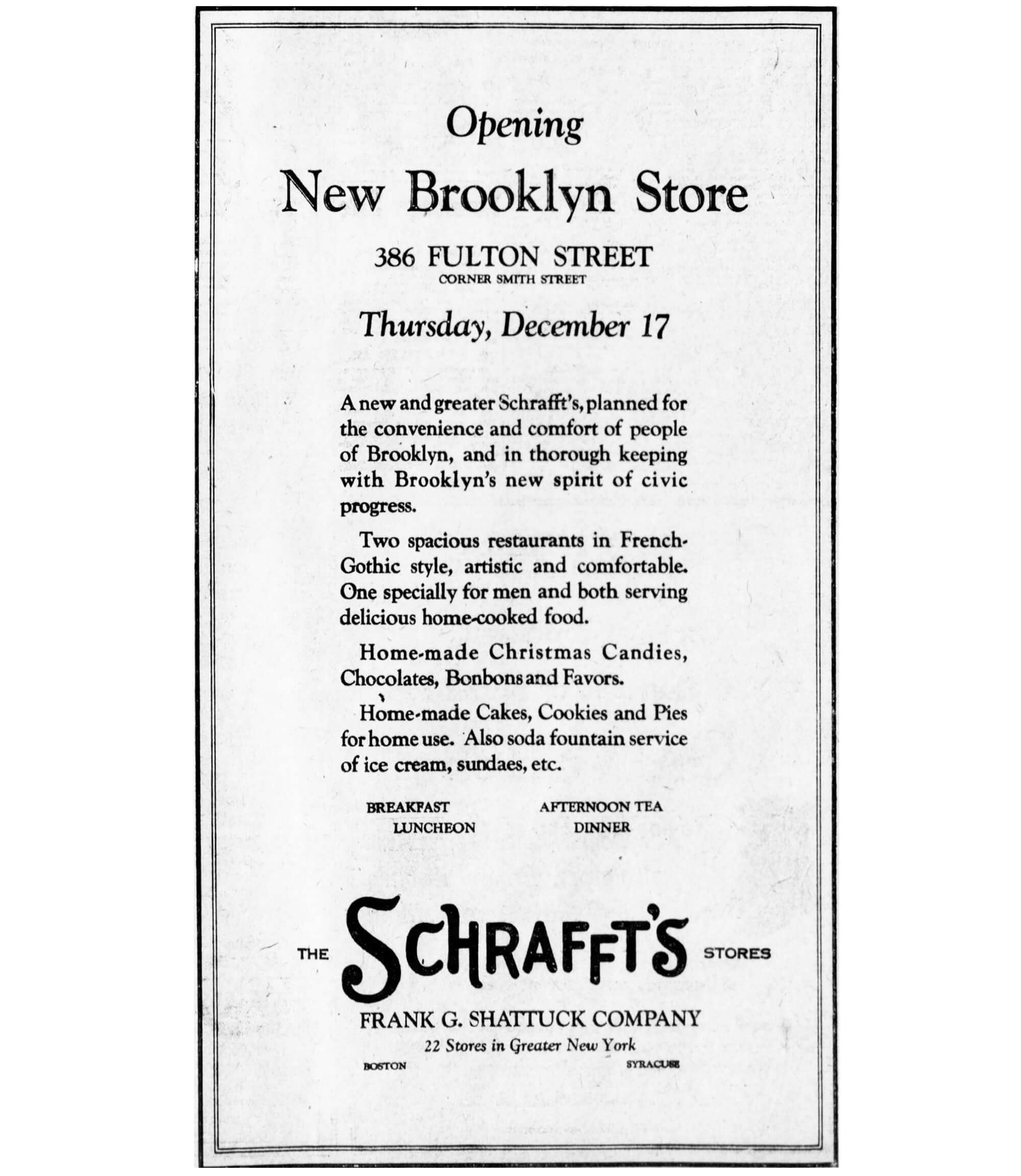

Schrafft’s was founded in Boston in 1861, by a candy maker named, not surprisingly, William F. Schrafft. In 1898, the company was taken over by Frank Shattuck, and it was he who expanded the company to include restaurants. They began to build in New York City, and by 1915, they had nine stores in Manhattan, one in Brooklyn, one in Syracuse and the Boston headquarters. By 1923, they had twenty-two stores, by 1934, there were 34, and by 1968, the company boasted a grand total of 55 Schrafft’s.

The restaurants were very popular with working women, as well as the ladies who lunched, and were very well appointed luncheon/tea places, tastefully decorated with Colonial Revival style furnishings in a backdrop of walnut paneling, delicate railings, and small intimate tables, plus a large counter or soda fountain. Schrafft’s Restaurants could be found in Boston, Philadelphia, New Rochelle, Syracuse, White Plains, and Newark, as well as the five boroughs, by the time they reached 55 stores, but they remain a quintessential New York kind of place for many people.

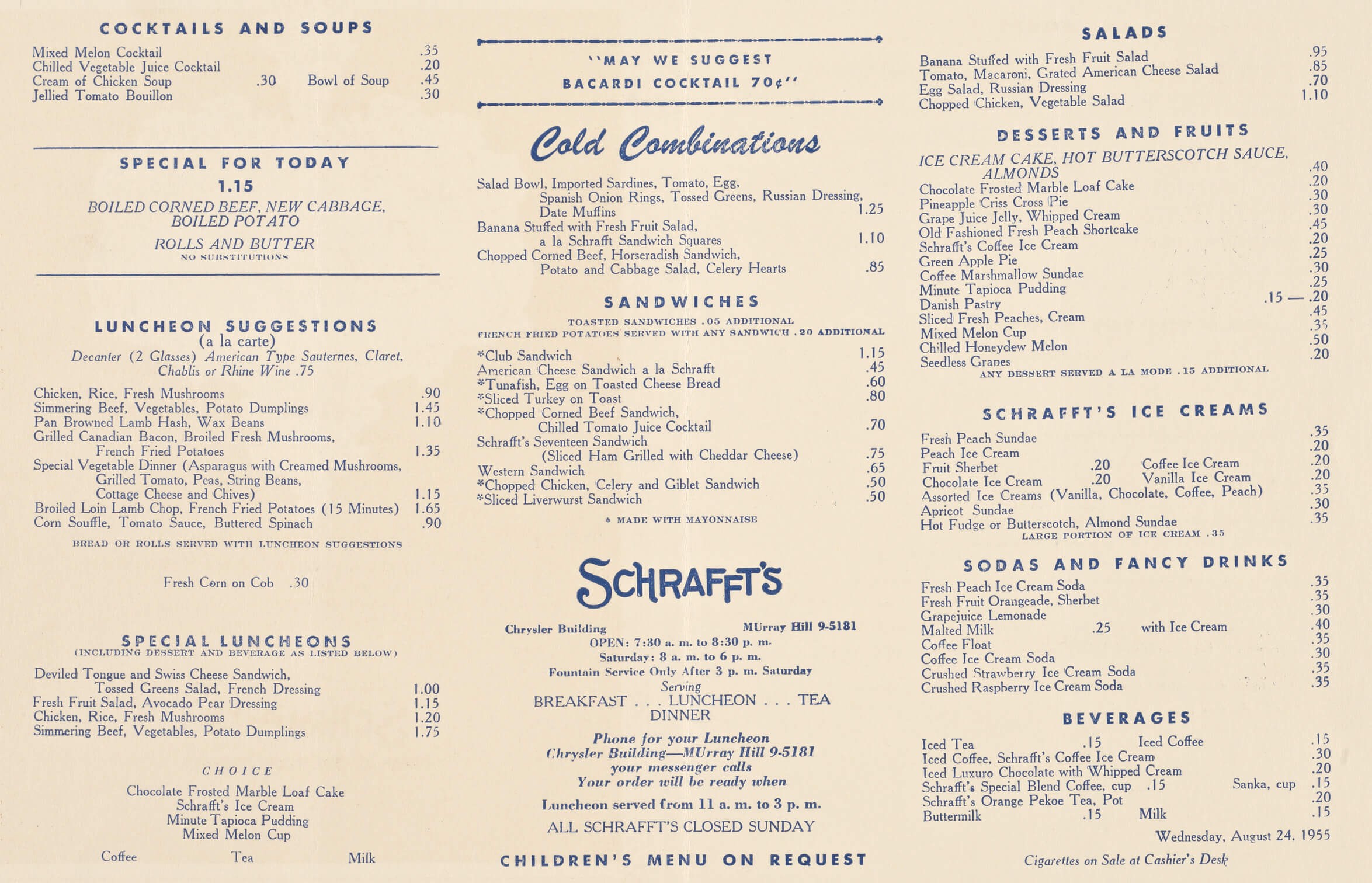

It was an elegant place to be, even if you were only having lunch. They also served breakfast and dinner, and after 1934, some places had a bar. Men were not admitted without a jacket, and management kept some in the cloak room, just in case. They served inexpensive meals with upscale names like “Crabmeat and Noodles Au Gratin”, “Chicken Liver Sauté on Toast”, and “Banana Omelet with Bacon Curls”. The restaurants would be filled with ladies shopping, the shop girls who would soon be waiting on them, nannies taking their charges for their famous ice cream sundaes, businessmen popping in for a quick lunch or dinner, and people meeting for an after-work drink.

The famous ended up at Schrafft’s. Kirk Douglas, as a young, starving actor, was a waiter at Schrafft’s. James Beard liked the preciseness of the egg salad sandwiches, while Truman Capote got thrown out of several Schrafft’s for being loud and rowdy. A young Jackie Bouvier used to come in with friends for ice cream. President Harry Truman stopped in at one once, and movies and novels used Schrafft’s as popular and familiar places to place their characters. In the 1961 classic movie,” Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” Audrey Hepburn’s character is filmed eating Schrafft’s food, with a logo bag at her side. It was such good advertising for the chain that as far away as 1998, Paramount Pictures released an Audrey Hepburn “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” doll holding a Schrafft’s bag and coffee cup.

Schrafft’s was also a good employer for women. Well ahead of their time, they were among the first to hire women as managers, and they had a profit sharing program, and had a pregnancy program for expecting employees. Because of this, many of their employees stayed with the chain for 25 or 30 years, an entire career. At one point there were more than 7,700 employees in the profit sharing program.

In spite of the popularity of the restaurants, the main reason to have them in the first place was to expose the customers to the candy. All of the stores had elaborate displays of candy in all of its glory. There were cases of individual candies from which you could choose. There was fudge and traditional chocolate candies, and fancy lollipops and other sugary goodies. There were stacks upon stacks of Schrafft’s classic box of chocolates; square boxes, round boxes, rectangular and heart shaped. All shapes and sizes and prices. There were gift baskets with colored paper and plastic wrap, often arrayed near the stairs to the restaurants, and anywhere else you could put them. From the minute you opened the door, you were bombarded with the possibilities of candy. Schrafft’s made a pile of money on candy, but in the end, their restaurants were responsible for 75 percent of their revenue.

But, as we all know, times change. By the late 1960s, Schrafft’s was known as the place where the “LOLs” ate. Not laughing out loud, but “little old ladies.” In an effort to make their image more hip, the chain hired Andy Warhol to do a commercial for them. It shows a shiny red dot, then the camera pulls back to show it is a maraschino cherry, which turns into a psychedelic swirl of color. At the end, a credit line rolls across the screen saying, “The chocolate sundae was photographed for Schrafft’s by Andy Warhol.” They also changed their ad campaign to show hip mini-skirted girls at Schrafft’s, the new “ladies who lunch.” In New York City, their interiors were remodeled, ditching the soda fountain to feature a bar serving alcohol, in an effort to draw men in greater numbers to the restaurants.

Earlier, in 1959, Schrafft’s sponsored the first telecast of The Wizard of Oz, on CBS. Less than 10 years later, in 1967, the entire company was purchased by the PET Milk Company, which broke the ice cream, candy, and restaurant operations into three separate companies. The restaurant company was sold to the Riese Organization, which at the time was snapping up luncheon places in the New York area. They bought Chock Full-O-Nuts, Child’s, Longchamp’s, and 26 Schrafft’s restaurants. They would later buy Beefsteak Charlie’s and TGI Friday’s. By the end of the 1970s, most of the Schrafft’s were gone, the spaces sold to the highest takers.

Schrafft’s candy division was bought by the Helme Products Company, which manufactured their signature boxed candy until 1981, when that too fell by the wayside, perhaps helped along by more upscale and hip brands of chocolate, such as Godiva. Today, only the ice cream remains in production. At least for the moment. According to a January 2019 story in the New York Post, Schrafft’s Specialty Foods is planning on bringing the restaurants back. The company president, a godson of the Shattuck family, told Page Six that the old recipes would be back, but not the prices.

Back in Brooklyn, there were at least two Schrafft’s. One was here, at 1 Smith Street, at the corner of Fulton and Smith. You can still see the Schrafft’s logo on the walls. It is a handsome limestone-block building with neo-Gothic details, built in 1925 when downtown Brooklyn was a vital and upscale shopping neighborhood. This building would have been in the thick of it, as the big stores, such as Namm’s, Oppenheim & Collins, Abraham & Straus, and Loesser’s were expanding, bringing more and more shoppers to the area. The metal hoods in the statue niches on the Smith Street side have a wonderful patination and are still quite intact.

Schrafft’s never used the entire building; part of the ground floor, the mezzanine level, and the entire second floor were used by John David, a clothier. He used the ground floor and mezzanine space for furnishings and hats, and the second floor was devoted to the clothing department. Schrafft’s took up the rest of the ground floor and mezzanine on the Smith Street side. I couldn’t find when this Schrafft’s closed, but it was quite a while ago, perhaps even before most of the Manhattan branches. In the tax photo from the early 1980s, it was Stereo Palace, which shared the Fulton Street frontage with a going-out-of-business dry goods store called Major’s.

Duane Reade has been there since the 1980s. Upstairs is now rented to a health clinic and a nonprofit. The original stoops on the Smith Street side, which led to the candy shop/restaurant, are gone, and the ground and second floor facades on Fulton Street have been totally modernized. Some detail can still be seen on the top floor, facing Fulton Street. The other Schrafft’s that there are photos of was at 912 Flatbush Avenue, in Flatbush, across the street from Erasmus High School.

Photographs of both shops, as well as many of the Manhattan Schrafft’s, are in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. The Fulton Street store was a Gothic castle confectionary. In total contrast, the Flatbush store was an Art Deco wonder.

Take a look at the candied goodness that was Schrafft’s. To see many of the Schrafft’s stores in their heyday of the 1930s, check out this link to the Museum of New York. Here you can really see how the chain established their brand identity.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- A Whirling Web of Art Deco Pattern on Flatbush Avenue

- A Downtown Brooklyn Brownstone Turned Rathskeller

- 5 Gone-but-Not-Forgotten Brooklyn Shopping Emporiums

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment