Borough President Launches Plan for Tackling Inequality in Brooklyn via Land Use and Funding

Antonio Reynoso has unveiled a comprehensive plan for improving equity in communities across Brooklyn, particularly in housing and health.

Photo by Susan De Vries

By Isabel Song Beer, Brooklyn Paper

For the first time since the 1960s, a borough president has unveiled a comprehensive plan outlining a vision and goals for communities across Brooklyn — specifically regarding issues of inequality in housing and public health, and how those issues are addressed through zoning and development.

Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso released his 201-page “Comprehensive Plan for Brooklyn” last week after over a year of intensive data collection and studies conducted through his office.

According to Reynoso, the plan is not a mandate but rather a sort of guidebook “intended to inform the borough president’s land use decisions and recommendations and to provide shared data and information to all Brooklyn stakeholders.”

The plan is a drastic departure from New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ moves to tackle city planning through zoning regulations, which divvy up land to establish how that land is developed.

“This document is in direct response to our city’s failure to plan,” said Reynoso in a press conference on October 4. “Because in New York City, we zone but we do not plan. Whereas most major cities have a comprehensive plan to guide growth, we do not.”

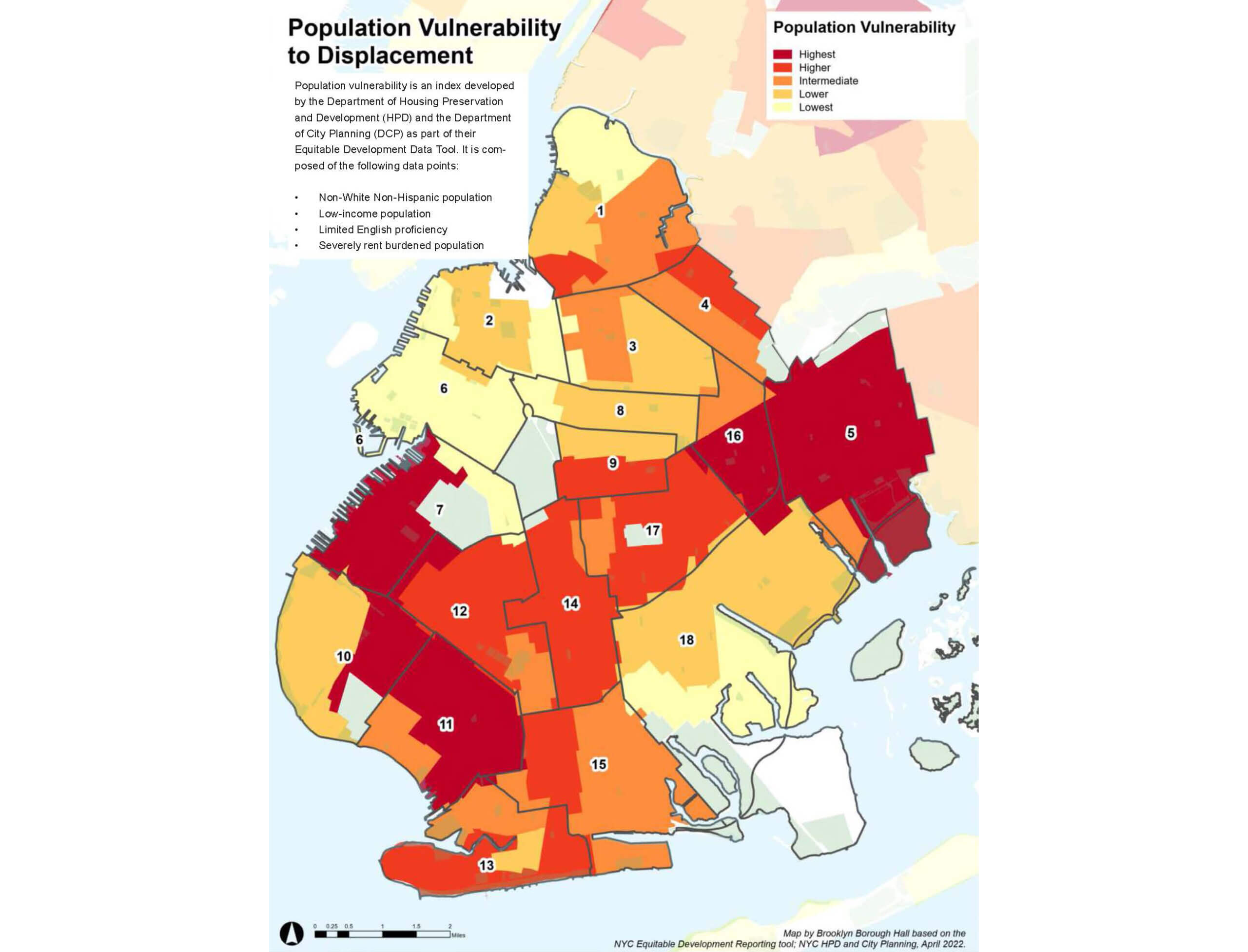

Reynoso’s office’s plan seeks to deploy the comprehensive plan to aid Brooklynites by addressing interconnected issues of housing and public health by suggesting Brooklyn communities make budgetary, policy, and land use choices that will benefit people who live in Brooklyn, rather than private land developers. Low-income neighborhoods of color are less likely to have access to quality healthcare, schools, transportation, and community services — all of which ties in to how development is planned and executed.

“Levels of homelessness not seen since the Great Depression, stormwaters flooding our streets and buildings, poor health outcomes in low-income communities — that is what a city that fails to plan looks like,” Reynoso said.

The plan diverges from the Adams administration’s zoning regulations, which Reynoso said are made up of arbitrary borders that have “nothing to do with connectivity, nothing to do with street safety, and everything to do with politics.”

Reynoso pointed to community boards across the borough which, due to zoning regulations and restrictions, are not equitably engaging in affordable housing development, which in turn harms marginalized communities borough-wide.

“Some neighborhoods got away with contributing no new affordable housing,” said Reynoso. “Between 2010 and 2020, Community Board 1 — which encompasses Greenpoint and Williamsburg — added 18,500 units of affordable housing, while Community District 18 — which encompasses Canarsie, Bergen Beach, Mill Basin, Flatlands, Marine Park, Georgetown, and Mill Island — only added 500 units.”

In the last decade or so, private developers have been eager to build apartment buildings in areas of Brooklyn where housing costs and demand are high, such as Community Board 1. If those developments take advantage of a rezoning or the now-expired 421-a tax break, as many do, owners are required to set aside a number of units as “affordable,” meaning income restricted and rent stabilized, although most of the units created under the programs are aimed at households earning well above the actual median. The city has concentrated its building of new apartments for formerly homeless, seniors, low and very low income families in areas such as Brownsville and East New York. Community District 18 has a high proportion of owner-occupied homes as well as the highest number of foreclosures in Brooklyn in the third quarter.

The comprehensive plan includes analyses of existing conditions throughout neighborhoods in the borough, and the data reveals a rather grim reality of intense inequities across different communities.

For example, in Community District 16 — which encompasses the neighborhood of Brownsville, a typically Black and Latino community — life expectancy is 76 years. In Community District 6 — Park Slope and Carroll Gardens — a predominantly white area, life expectancy is about 82 years.

Using data collected from all community districts throughout Brooklyn, Reynoso’s office developed the comprehensive plan to present recommendations to address the disparities across the borough concerning housing and public health.

“Disparities are not just seen in housing,” Reynoso said. “We see disparities in the fact that Black women are 9.4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than their white counterparts and the fact that 90 percent of all childhood lead poisoning cases involve children of color.”

The pattern of these inequities, Reynoso said, is no coincidence. The current model of city planning that relies on zoning regulations is disjointed across city agencies and disregards the realities of how people interact with and experience the city.

According to Reynoso, city agencies like the Department of City Planning and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development do not collaborate, leading to poor information sharing and little to no guiding principles.

Instead, these city agencies defer to community boards and council district boundaries to plan, even though these boundaries often have little to do with how Brooklynites actually move about or interact with their communities.

“The result is a city designed not for the good of the people, but for the gains of the private sector,” Reynoso said. “And because residential space is so much more lucrative than, say, manufacturing space, districts are eroded and career pathway jobs are limited for those without advanced degrees or who speak languages other than English.”

While the plan offers up recommendations, it is not a substitute for citywide comprehensive planning or ongoing local planning efforts, Reynoso said. The plan is intended to act as a “living document” used to inform the borough president’s office on land use decisions, and to provide exhaustive and comprehensive data to all Brooklyn residents and stakeholders.

“In cities around the world, comprehensive planning is the norm,” said Reynoso. “Comprehensive planning balances local and citywide needs so that all residents have equitable access to the resources that lead to healthy communities. My comprehensive plan for Brooklyn maps disparities across Brooklyn and puts forward a roadmap to solve these inequities.”

The report’s recommendations focus on areas within the powers of the Brooklyn borough president: Advocacy and outreach, land use, and budget.

Recommendations include funding, regulation, appointments, and more to improve healthcare, increase production of affordable housing, and reduce violence in Brooklyn. For housing development requiring public approval for a rezoning, Reynoso proposes asking developers to meet with the community ahead of the formal review and to offer deeper affordability than currently required.

Following the release of the comprehensive plan, Brooklyn leaders and various experts applauded the borough president for beginning the process of addressing and healing community disparities.

“This comprehensive plan for Brooklyn will put our borough on track to deliver much-needed housing, drive positive health outcomes, and improve the quality of life for the people that live and work here,” said Regina Myer, president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership. “By rethinking how Brooklyn works for everyone – starting with our infrastructure – we can create a healthier, more sustainable, and equitable city.”

This sentiment was echoed by Moses Gates, Vice President for Housing and Neighborhood Planning with the Regional Plan Association.

“The Comprehensive Plan for Brooklyn demonstrates how planning can be responsive and proactive in meeting the needs of communities across a wide range of issue areas,” Gates said. “Addressing high housing costs, improving health outcomes, adapting to climate change, enhancing transportation networks, and ensuring equitable economic development can only be done through a comprehensive and integrated approach.”

— Additional reporting by Cate Corcoran

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- Mayor Adams Outlines Plans to Make Way for More Housing and a ‘City of Yes’

- What Is Affordable Housing?

- NYC Has More Housing Than Ever Before Yet It’s Still Not Affordable

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment