Walkabout: Sidney Painter’s Funeral

Unfortunately our columnist’s computer problems are continuing today so we are republishing a Walkabout from a few years ago. Photo: First AME Zion Church, McDonough at Tompkins. Bedford Stuyvesant. Home of this congregation since 1947. Sidney L. Painter was a well-known Negro band leader in turn of the 20th century Brooklyn. He hailed from the…

Unfortunately our columnist’s computer problems are continuing today so we are republishing a Walkabout from a few years ago.

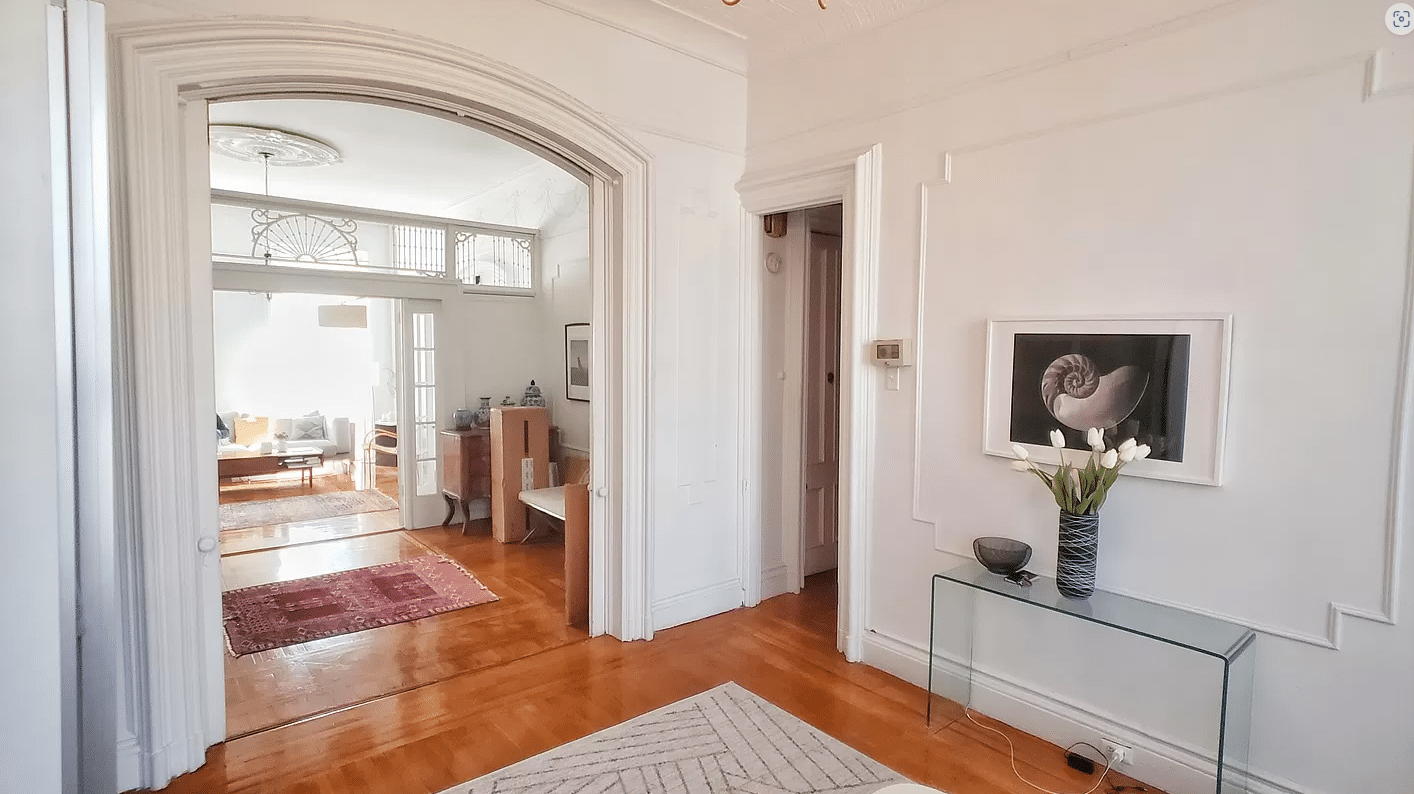

Photo: First AME Zion Church, McDonough at Tompkins. Bedford Stuyvesant. Home of this congregation since 1947.

Sidney L. Painter was a well-known Negro band leader in turn of the 20th century Brooklyn. He hailed from the Wichita, Kansas area, but when he died in February of 1905; his funeral took place at the First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on Fleet Street, in downtown Brooklyn. Brooklyn’s had several large African-American communities, as Brooklyn has always had African-American residents, and at this time, one of the largest communities was centered in the area of downtown Brooklyn near Fleet and Concord Streets, near Hudson and Myrtle Avenues, in the area now occupied by Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute and the northern part of MetroTech. The black community there had a long history of religious participation, and several of modern day Brooklyn’s largest black churches got their start in this community.

The First AME Zion Church on Fleet Street had originally been built as the Fleet Street Methodist Episcopal Church, in 1849. It was a large two story wooden structure with a gabled roof, but no steeple. Inside, it had a large open downstairs room that was used for Sunday school classes and church events, and upstairs was the church sanctuary, with two aisles, and three rows of benches. In order to get upstairs, people had to go up one of two stairways on the left and right of a hallway. These stairs were narrow, and about halfway up, turned on themselves, before continuing upstairs. The church had been sold to the black congregation about twenty years before, and was one of the more important houses of worship in this downtown black community. A celebrity like Sidney Painter would bring out a large crowd for his funeral. Unfortunately, death would be there to claim more than Mr. Painter that day.

The old church was a rather badly built and rickety structure, and was one of the oldest buildings in the area. In the fall of 1904, city building inspectors had deemed it dangerously unstable and condemned it. The pastor, the Reverend F. M. Jacobs, had pleaded with the building department to give them enough time to relocate. The inspector relented, under the condition that large gatherings not be held in the space. The pastor agreed, as not all that many people were ever in the building at one time, and the congregation was relatively small. But he didn’t count on the 8pm funeral of Sidney Painter.

Painter had been a popular band leader, and had conducted an orchestra and choir, all of whom had turned out for his funeral, and were in the front of the church, ready to participate in the service. He was also a member of the local (colored) chapter of the Elks, and his entire lodge was gathered downstairs in the Sunday school, in full regalia, with banners and flags, waiting for the casket to arrive, which they would escort into the church. In the pews and benches were hundreds of mourners, over 500 people, in total. Because of the large crowd, a policeman named McCree had been ordered to stand in at the church. He was on the second floor when the Reverend Jacobs realized that there were far too many people in the church. He called out to Officer McCree to have him help clear the aisles, but his cries were either not heard or ignored.

Rev. Jacobs left the pulpit, and went into the crowd to get them to sit down. At the same time, the undertaker entered the church with assistants bearing large floral arrangements and wreaths. They headed up the western aisle of the church, causing two thirds of the people to crowd onto one section of the floor. The floor of the sanctuary consisted of one inch planks resting on three inch cross beams. Those, in turn, rested on two one foot thick string beams that ran the length of the building. Each one of these beams had extra support from two iron columns of only three inches in diameter. All of the people crowded into a weak area of the floor caused one of the stringers to snap like a twig, and with a loud crack, dust began to rise up from the floorboards below. Someone yelled “Fire!”, and a panic ensued. People began crowding each other and moving heavily across the floor. In a matter of seconds, the center of the floor collapsed, taking the pews and the people on them, into a maelstrom.

As the screams and cries rose up into the church, people were hanging onto pews that were lurching downward into the huge hole in the center of the building. As soon as the collapse happened, the gas lines were damaged, and the lights went out. This saved the building from fire, but the darkness caused even more panic. The collapsed materials missed the wood stove that heated the Sunday school room by only a couple of feet. Had it fallen over, a disastrous fire would have killed far more people. The Elks, who were gathered to march in behind the casket, were all lined up under the part of the floor that did not collapse, and they were able to escape unharmed. Outside, a large crowd had gathered for the funeral, estimated to be over a thousand people. When the cry of “Fire” came, and then the collapse happened, many of these people turned and ran from the scene. In the melee, Officer McCree was able to get to the street and run to the nearest fire box and call in the alarm. Three engines and two trucks responded, and as soon as they saw their hoses were not needed, the firemen began removing the rubble and pulling the victims out, throwing benches and pews out of the windows picking through the injured and dead.

In spite of the panic, one man, a church Trustee named Alexander Rhone, kept his head and became a hero. He had been downstairs in the Sunday school room when the collapse happened, and was able to jump out of a window to safety. He then got two tall ladders from the alley and put them up to the upper windows on the eastern side of the church. He was able to assist scores of people out of the building safely. Reverend Jacobs had gone down with the floor, and was actually standing at the spot where the beam broke. Although he wrenched his leg, he was helped out of the hole, and out of a window. He somehow walked home, where he was unable to recall anything after the floor collapsed beneath his feet.

The police and ambulances began to gather the wounded and the dead. Eleven bodies were pulled out of the wreckage, and many more people were seriously wounded. All of the people had died as a result of being suffocated under the massive weight of the debris and the crush of other people. Most of the dead were women; one was a two year old child. In the aftermath of the disaster, it was found that the stairwells between the two floors were responsible for saving many more lives, as the double backed stairwells supported the floors long enough to allow people to escape. Also instrumental was the presence of a back exit, built as a condition of keeping the building open, after it had been cited and condemned. This exit also saved many lives that day.

Borough Superintendent Littleton and Superintendent Collins of the Building Department inspected the site the day after the collapse. Collins said that a “violation” had been issued against the building. He also said that the white pine beam that broke must have been very brittle, but that was impossible to ascertain in an inspection. He didn’t think anyone could have predicted the accident, and that no one of authority was responsible. Several members of the congregation thought differently. In the months that followed, eight separate law suits were filed for damages, totaling $150,000. They were filed in Brooklyn Supreme Court, all against Superintendent Collins, personally, on the grounds that he had neglected his duty.

There are no records of these suits being won and more than likely, the lawsuits by eight “colored” people against a prominent city official were either tossed out, or quietly taken care of. Peter J. Collins was only Superintendent of Buildings for a year, between 1904 and 1905. Perhaps this case caused the end of that career. It didn’t stop him in his other career, that of successful architect and developer. Collins and his brother, Frank, also an architect, would be among the major developers of Prospect Lefferts Gardens. Between 1915 and 1919, their company, the Brighton Building Company, would build several rows of buildings in that neighborhood, among them two streets of unique Tudor style attached cottages. Collins would also build one family and flats buildings in Park Slope and Prospect Heights. He lived in a house designed by his brother Frank, in Prospect Park South.

The First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church also prospered. Like many of downtown’s black churches, including Concord Baptist, Bridge St. AME, and Siloam Baptist, in the 1920’s and ‘30’s, they moved to Bedford Stuyvesant, as that neighborhood became the new heart of Brooklyn’s African-American community. In 1947, they bought the large church on the corner of MacDonough Street and Tompkins Avenue, once belonging to the Tompkins Avenue Congregational Church. Today they are one of Brooklyn’s largest churches. Its cornerstone bears a plaque honoring the Fleet Street church.

Photo via Facebook

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment