The Red Hook Houses: Housing Brooklynites During the Great Depression

When NYCHA was founded in 1934, one of their first proposals for Brooklyn was a housing project in Red Hook.

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

Housing projects were originally built as a great experiment to house lower income people, one of many to come from the unprecedented poverty and needs of the Great Depression. The economic conditions that brought nationwide misery to this country beginning in 1929 and continuing throughout the 1930s were so bad it would take a world war to break the nation out of their grip.

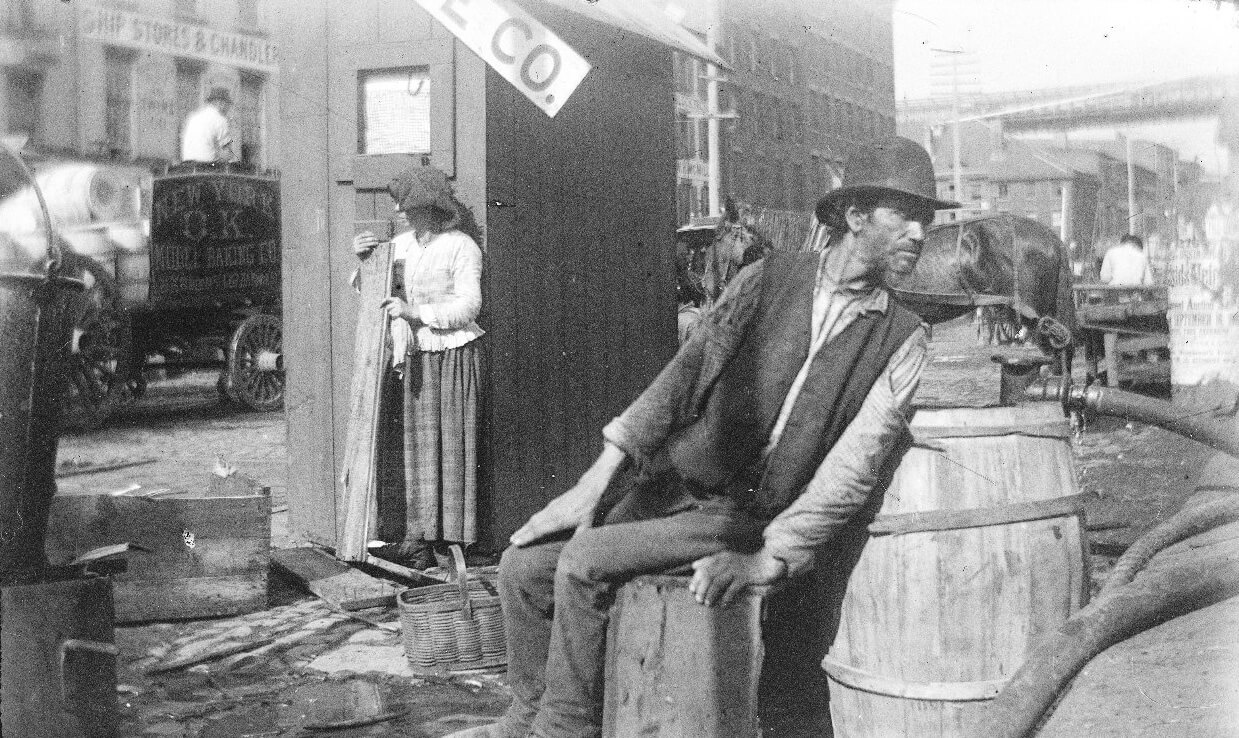

Between the turn of the 20th century until about the early 1960s, Brooklyn was a manufacturing town. Red Hook, and the piers along the East River were important economic centers. Ships came into Brooklyn’s harbors and docked at her many piers, with goods from all over the world. At the same time, goods from Brooklyn’s many factories and warehouses needed to be shipped out.

These goods could be raw materials for manufacturing, as well as any imaginable combination of imports, foodstuffs, commodities or products. All of it had one thing in common — it all needed to be offloaded, loaded or stored.

Red Hook’s piers had come a long way since their early days. Sailing ships became merchant steamships while horse-drawn carts became trucks. But people were still needed to move the goods, creating a world of longshoremen, dock workers, truckers and stevedores.

The 19th century dockworkers were mostly immigrants or the children of immigrants. The earliest were Irish, German and Norwegian. By the 1890s, they were joined by Italians and some African Americans. The early 20th century brought Puerto Ricans.

Working on the docks was backbreaking work, and often dangerous. Added to this was Red Hook’s growing reputation for hooliganism, rowdy sailors, gangs and organized crime. The most infamous gangster of all, Al Capone, grew up on these docks.

Housing Red Hook’s Workforce

Red Hook, which still retains some of Brooklyn’s oldest housing stock, started out with frame houses. They were followed by brick rowhouses, and later multi-family tenements. But the area’s residential housing stock could never satisfy the ever-growing number of people and families that came there to work and live. The existing single-family housing stock was soon subdivided into apartments and rooms.

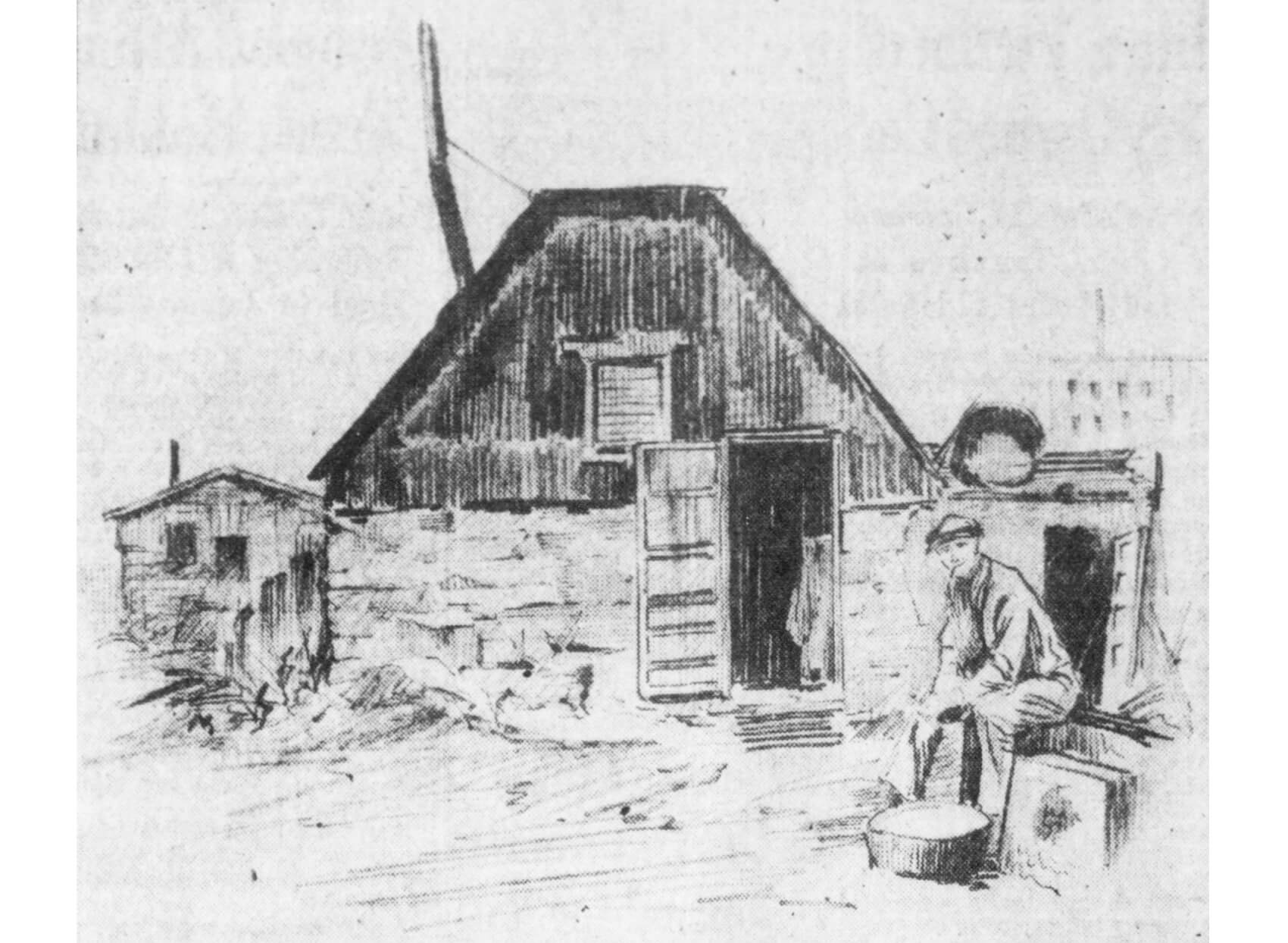

Vacant land not being used for anything was appropriated by shanty towns that seemed to spring up overnight. One such shanty town in the 1880s was called “Slab City.” More than 2,000 people squatted there, in scrap wood shacks, along with their livestock. It was disgraceful. Reporters from the Brooklyn Eagle came down to look at the people and how they lived, and came back with tales of dire poverty and misery.

The city of New York tried on several occasions to make conditions better. They purchased some land for a park and a baseball fields — part of it where today’s Red Hook Play Center stands today. But there were no programs at the time to provide housing for people. Any relief efforts were arranged through private charities. “Slab City” and its like were cleared, but a desperate need for Red Hook housing remained.

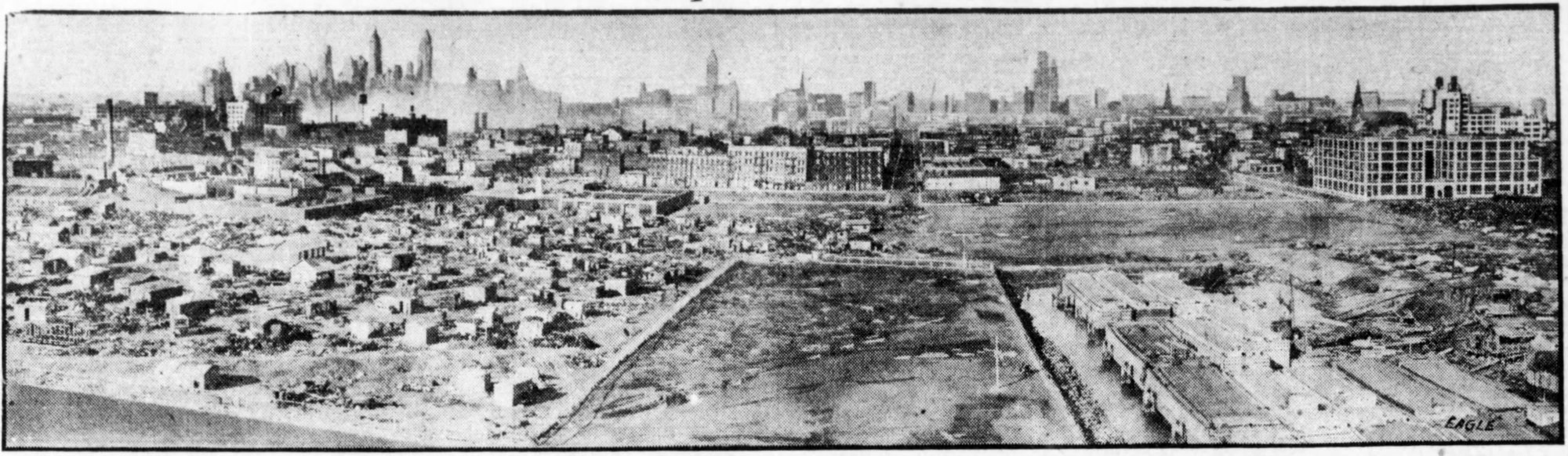

By the time the Depression was in full swing in the early 1930s, conditions in Red Hook still looked like the 1880s. Red Hook became the location of one of the city’s “Hoovervilles.” These were corrugated tin shacks and tent cities created by homeless and displaced people, named for the country’s president, Herbert Hoover. More than 400 people lived in this camp surrounded by rusting automobiles and trash, nicknamed “Tin Can Mountain.” Most of them were dockworkers and their families.

The idea of building public housing for these people was floated in City Hall, with a man named Lewis H. Pink, of the New York State Housing Board, advocating for its creation. Pink wanted to build a mixed community on a large city parcel consisting of a mixture of row houses, apartment buildings of varying heights, stores, a movie theater and a park.

This was in 1933, before the creation of the New York City Housing Authority. Unfortunately, Robert Moses also wanted the land for a Red Hook Park and recreation center. He won. Tin Can Mountain was torn down, the people told to go somewhere else, and the site was cleared for the Red Hook pool and recreation center.

But Pink’s idea of public housing in Red Hook stayed with the committee. When NYCHA was founded in 1934, one of their first proposals for Brooklyn was a housing project in Red Hook. The Williamsburg Houses ended up being first, but Red Hook wasn’t far behind it.

The Architect: Alfred Easton Poor

Franklin D. Roosevelt was now president. The Red Hook Houses were part of his federal Works Progress Administration, designed to put people back to work, as well as provide housing and other public projects. The chief architect for the project was Alfred Easton Poor. He was born in Baltimore in 1899, and grew up in New York City. Poor was educated at Harvard and got his masters in architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His early claim to fame was in winning the commission to design the Wright Brothers National Memorial at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1932.

Poor worked primarily in the New York City area, and was also responsible for several important projects in Washington, D.C. When the Depression hit, his firm was making a handy living designing country homes on Long Island. He worked on other housing projects, but is credited for the entire design of the Red Hook Houses.

After World War II, Poor’s firm, Walker & Poor, began designing bank branches for National City Bank, (now Citibank), along with Chemical Bank and Marine Midland Bank. He was also responsible for the design of the New York Customs House in Foley Square in Manhattan as well as the Jacob Javits Federal Building, also in Lower Manhattan.

Other Poor buildings include the Library of Congress’ James Madison Memorial Building, the Queens County Criminal Court and jail in Kew Gardens, and the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. Most of these were built in the 1960s, before his retirement in the 1970s. Poor died in New York City in 1988, at the age of 88.

Constructing the Red Hook Houses

The original Red Hook projects are now known as the Red Hook East buildings. They consist of 27 buildings of two and six stories. Ground was broken on the 40-acre site on July 17, 1938. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia laid the first cornerstone in a grand ceremony. The buildings were completed about a year later, with the first tenants moving in on June 30, 1939.

Unlike later NYCHA housing, the early housing projects were not the now-familiar double-digit storied towers arranged in a park setting. These houses had a lower scale and density, and were built as rambling rectangular shapes on their lots, with long hallways allowing for apartments with lots of windows for fresh air and ventilation. Most of the buildings had six stories.

Later additions to the houses, called the Red Hook West buildings, were built in 1955. They consist of a combination of taller 14-story towers and three-story buildings. Today, the East buildings house over 2,500 people, the West buildings house around 350.

Life in the Red Hook Houses

The buildings had self-operating elevators, incinerator chutes in the hallways, and basement laundry rooms. Each apartment had a full kitchen with a gas range and a refrigerator. The buildings were well built, but corners were cut to save money. The closets did not have doors, a feature noticed by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt when she visited four apartments in the complex in 1940.

The tenants were all Irish and Italian dockworkers and their families. While the buildings were being constructed, the new Housing Authority received more than 1,000 applications a day from would-be tenants. There were only 2,800 apartments.

The tenants who were chosen had to go through a rigorous application and interview process. The Brooklyn Eagle noted in 1939 that the cap on family income was $1,399 a year, a number many, including the mayor, thought was too high. The would-be tenants also had to come from housing that was “injurious to health, safety and morals.”

A panel of prominent psychological and social experts visited the homes of those who were in serious contention. Investigators wanted to see if the applicant were truly living in poverty, and if their current living conditions had falling plaster or other damage. They were also interested in seeing if the living conditions were otherwise clean and neat.

They also looked at family life, church attendance, school performance and other “moral” standards. City officials wanted to be able to show that the people who moved into the Red Hook Houses were the best of the “deserving poor,” as there was a lot of public blowback to project housing then, as there is today. Those who were chosen were beyond pleased. The first rents in the Houses were as low as $6 month.

Moving In

On a sunny July 4th of 1939, Independence Day, the first 114 families were welcomed by Mayor LaGuardia as they settled into their new homes. A grand assembly was held in the central courtyard. The event was marred by labor disputes which were holding up the completion of all the buildings. Hecklers were also in the crowd, said to be sent there by unscrupulous slumlords who didn’t want people to leave their squalid apartments for the new projects.

But Mayor LaGuardia was his usual upbeat self, and noted that he had experienced a “real thrill” in seeing the project being completed, and the first families moving in. Other housing officials also reported how pleased they were to be able to offer new apartments, as they worked diligently to close down slumlords and substandard housing for the working poor. Architect Poor announced that the project had saved money in construction and represented a judicious and careful spending of federal money. Before the ceremonies, a new park was dedicated amid the Houses. All was well in Red Hook that day.

Much would change in the Red Hook Houses over the next 60 years. But that is a story for another time.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment