Taking a Risk During a Building Boom in 19th Century Crown Heights

A developer, eager to capitalize on a building boom, a robust economy, and a hot neighborhood, takes a chance to build what he feels will be hugely successful and lucrative housing.

Hampton Place. Photo by Susan De Vries

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2010. Read the original here.

A developer, eager to capitalize on a building boom, a robust economy, and a hot neighborhood, takes a chance to build what he feels will be hugely successful and lucrative housing. But while everything seems to be in his favor, something happens, and the bottom falls out and bankruptcy looms. Will he succeed? Will the housing be built? More importantly, will it sell? What happens? Here on Brownstoner, we read about these situations every day, it seems. But this tale is not about Williamsburg or Park Slope in 2014. It’s about the St. Marks District, now called Crown Heights North, and the year is 1898.

At the end of the 19th century, the St. Marks District was one of the most fashionable areas of Brooklyn. As the mansions of the rich were going up on St. Marks Avenue, and adjacent streets, new blocks of more modest housing was going up all around the area. Most of this was speculative housing, and the developers of yesterday were doing much of what today’s developers are doing — trying to build in a popular neighborhood for those who could afford it. Sometimes this involved taking an innovative approach with a marketing hook. In this case, developing an exclusive enclave of two short blocks tucked in between two popular streets, and in between two busy avenues, all a block or two from a beautiful new park.

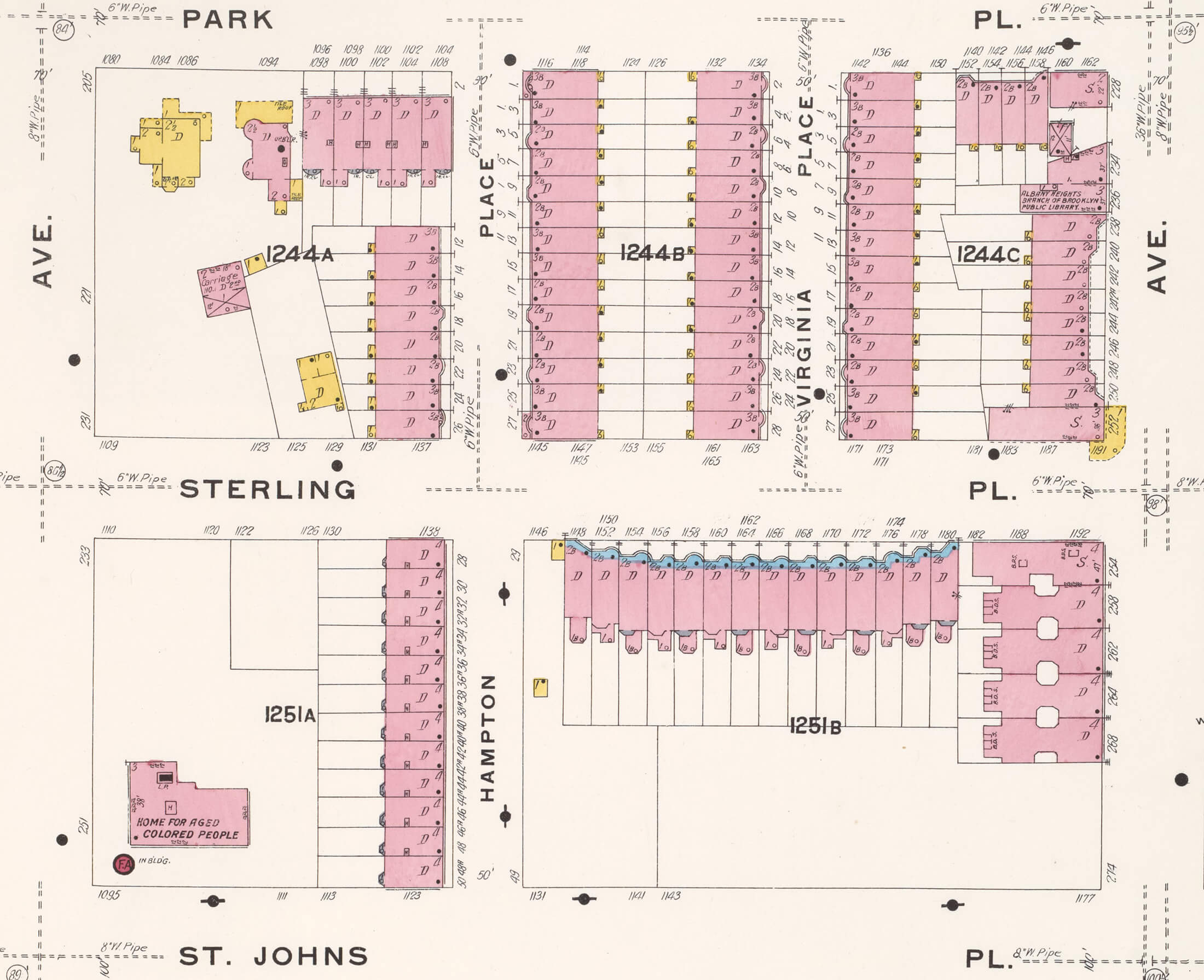

Hampton Place and Virginia Place are both only two blocks long, and are parallel to each other, and to busy Albany and Kingston Avenues. The blocks in question are between Park and Sterling Places. By the 1890s, the street grid had been laid out, but Hampton and Virginia Place were not included. The land was originally owned by Ellis G. Porter, who traded it to a Howard R. Deacon for an extensive hotel property in Virginia Beach, Va., along with a building loan of $225,000. This may be where the Virginia and Hampton names originated.

Deacon sold the land to fellow Philadelphians, Charles C. Haines and Hames A. Campbell, who were experienced developers in that city. Deacon also took back a mortgage for $20K. The first thing Haines and Campbell did was to cut through the property and lay out Hampton and Virginia Places. The idea was to create an exclusive enclave, tucked away from the city grid.

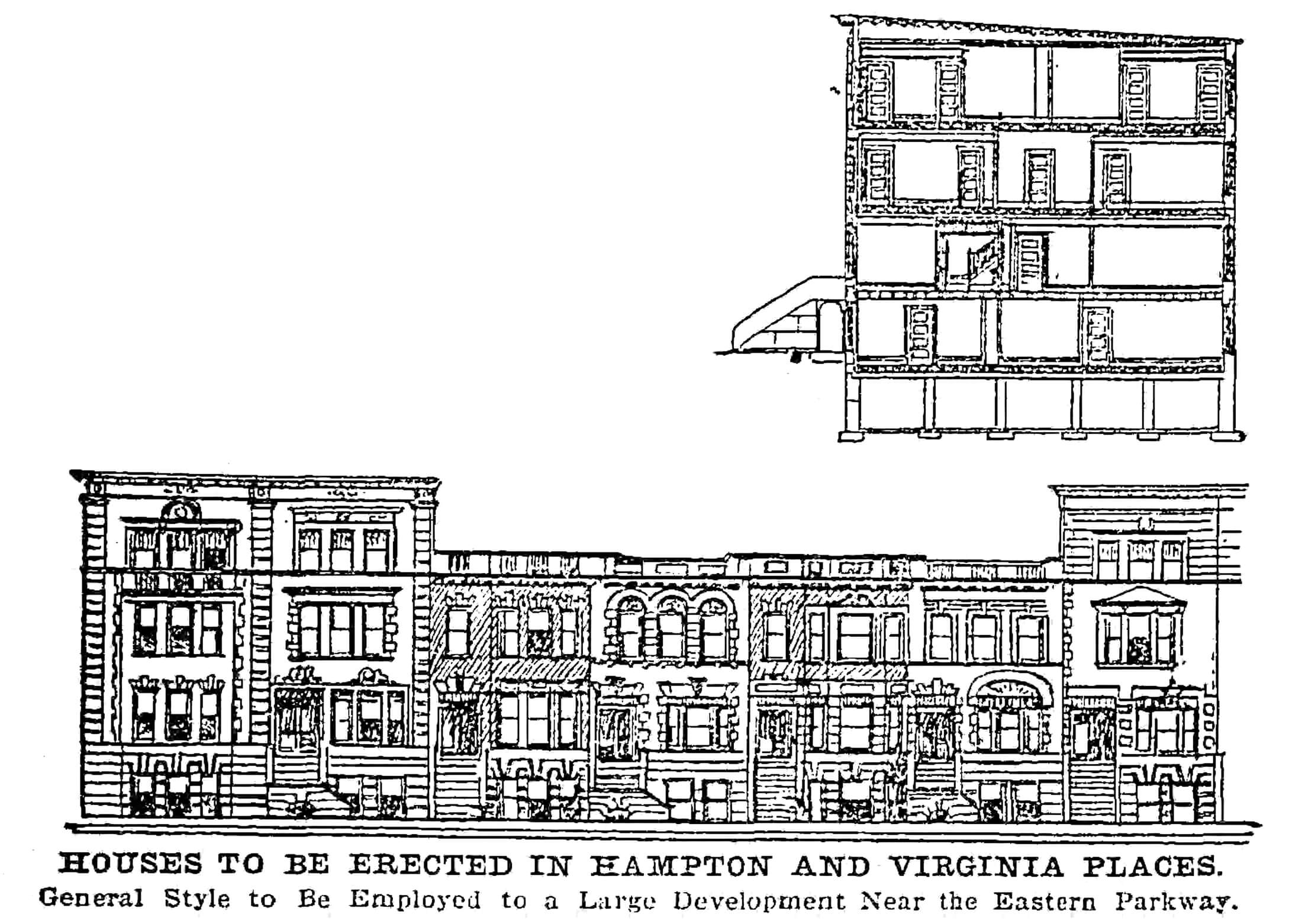

The design of the houses would be a unique mixture of 50 houses, 23 three-story and basement houses, along with 28 two-story and basement homes, all designed by the same architect, all joining harmoniously in a two block cohesive unit. Each block would contain fourteen houses, two three-story houses on each corner, and two in the center of the block, with the west side of Hampton Place only having eight houses. The houses were designed by Charles Betts. Construction started and by mid-year, 1900, the houses were enclosed and some had their exterior trim. Then the trouble started.

Charles Haines began advertising the unfinished houses for sale in groups in ads in the Brooklyn Eagle, in July of 1899, offering 12 two story houses on Virginia place for $78k, and 8 on Hampton Place for $68K, and 16 houses on both streets for $114K. There must have been no takers. In November of 1900, Howard Deacon filed suit against Haines and Campbell, alleging that they had defaulted in their interest payments, and were unable to finish the project. Deacon demanded his $20K be paid immediately. In court, it was learned that Haines and Campbell had a builder’s loan of $225K, of which $185,835 had been advanced, and liens of $21,564.92, plus $328.33 were drawn on the properties, along with taxes and expenses of $2,342.79. Needless to say, they didn’t have it, and the judge foreclosed.

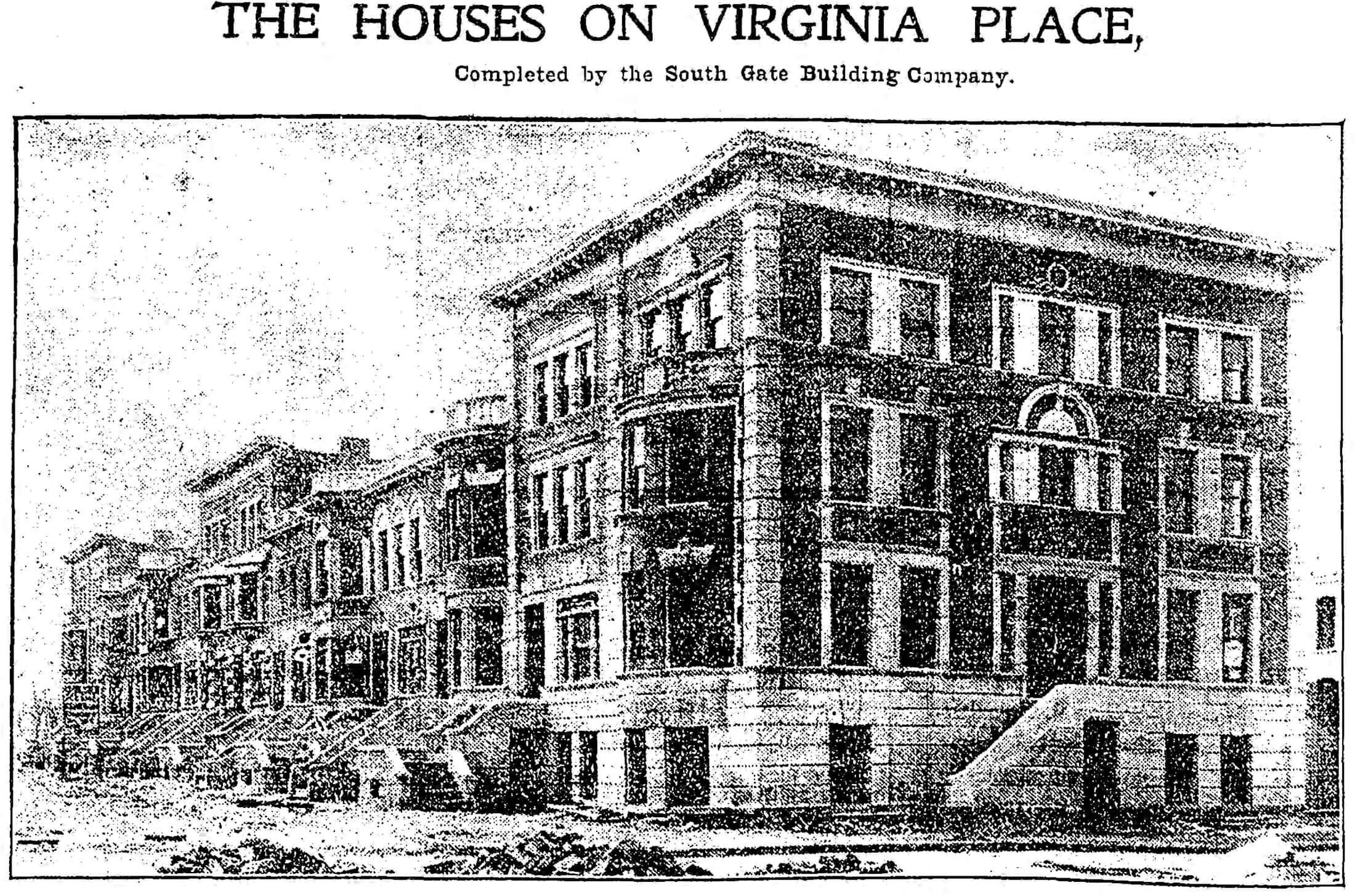

A month later, the properties were auctioned, and sold back to Howard Deacon for $191,000. In 1902, the Hampton-Virginia development is again in the news, announcing that the houses were almost done. The company of record is the South Gate Building Company. I could not ascertain if this was Deacon’s business, or if he had sold it, or partnered in order to finish. The article, published in March 1902, is accompanied by a photograph showing the new row of houses, with unfinished streets and sidewalks.

The article says that, “the 50 houses on Virginia and Hampton Place in the St. Marks section, upon which work was long delayed, are practically completed. The streets are not yet laid, but they will be asphalted and curbed within a few weeks. These houses, built on a street one block long, make a very exclusive neighborhood and their architectural style add to the beauty of the locality. The South Gate Building Company is the contractor who finished the houses.”

Ads for the houses start to appear in the Eagle in April, offering the smaller two stories plus basement houses for rent at $45/month, or greater, or for sale at reasonable terms. On May 10th, the Eagle announced that the first house had been sold to a Mr. Arthur S.R. Smith for $6,500, and that the streets and sidewalks were being laid. Hampton and Virginia Places were finally finished.

Today, the streets remain an isolated enclave, quiet and peaceful. The houses are all Renaissance Revival in design, made of gold or red brick with white limestone trim, featuring swags, garlands, columns and other classical details. Over the years, some have fared better than others, but the streets remain remarkably intact, especially Hampton Place. The interiors of the houses reflect their Renaissance Revival/Edwardian-era details: fine oak parquet floors, oak trim in restrained and simpler woodwork and fireplace surrounds, classical columns as parlor dividers, and very simple stained glass.

Most have been owned for generations by the same families, and new owners have also found these homes to be quite desirable and have put both stamp on them, with both period restorations and modern gut rehabs. This area also boasts one of the strongest block associations in Crown Heights North, advocating for historic district designation, as well as improvements to nearby Brower Park. The streets were included in the Crown Heights North III Historic District, landmarked in 2015.

Charles Haines and Hames Campbell may not have been able to finish their grand project, but one over one hundred years later, their exclusive enclave still stands as a testament to some bad business practices, but excellent real estate development planning.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Building a Borough: The Brick Buildings of Brooklyn

- Adding the Final Flourish: Ornamenting With Ironwork

- This Exuberantly Colorful Terra Cotta Building in Crown Heights Housed Bowling and Billiards

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment