Medallion Matters: The History and Care of Plaster Ceiling Medallions

Popular in 19th century homes, plaster ceiling medallions offer a visual transition and seat for a light fixture in important rooms.

A Neo-Grec-style medallion from a house in Bed Stuy. Photo by Susan De Vries

Popular in 19th century homes, plaster ceiling medallions offer a visual transition and seat for a light fixture in important rooms. Their elaborate bas-relief designs also helped hide soot from oil and gas lamps.

They were de rigueur in the main entrance hall, parlors, dining room, and large bedrooms. In Brooklyn, you will not find them in small side bedrooms, halls, or bathrooms, where wall sconces would be used, nor in kitchens, where a J-hook might hang over the sink.

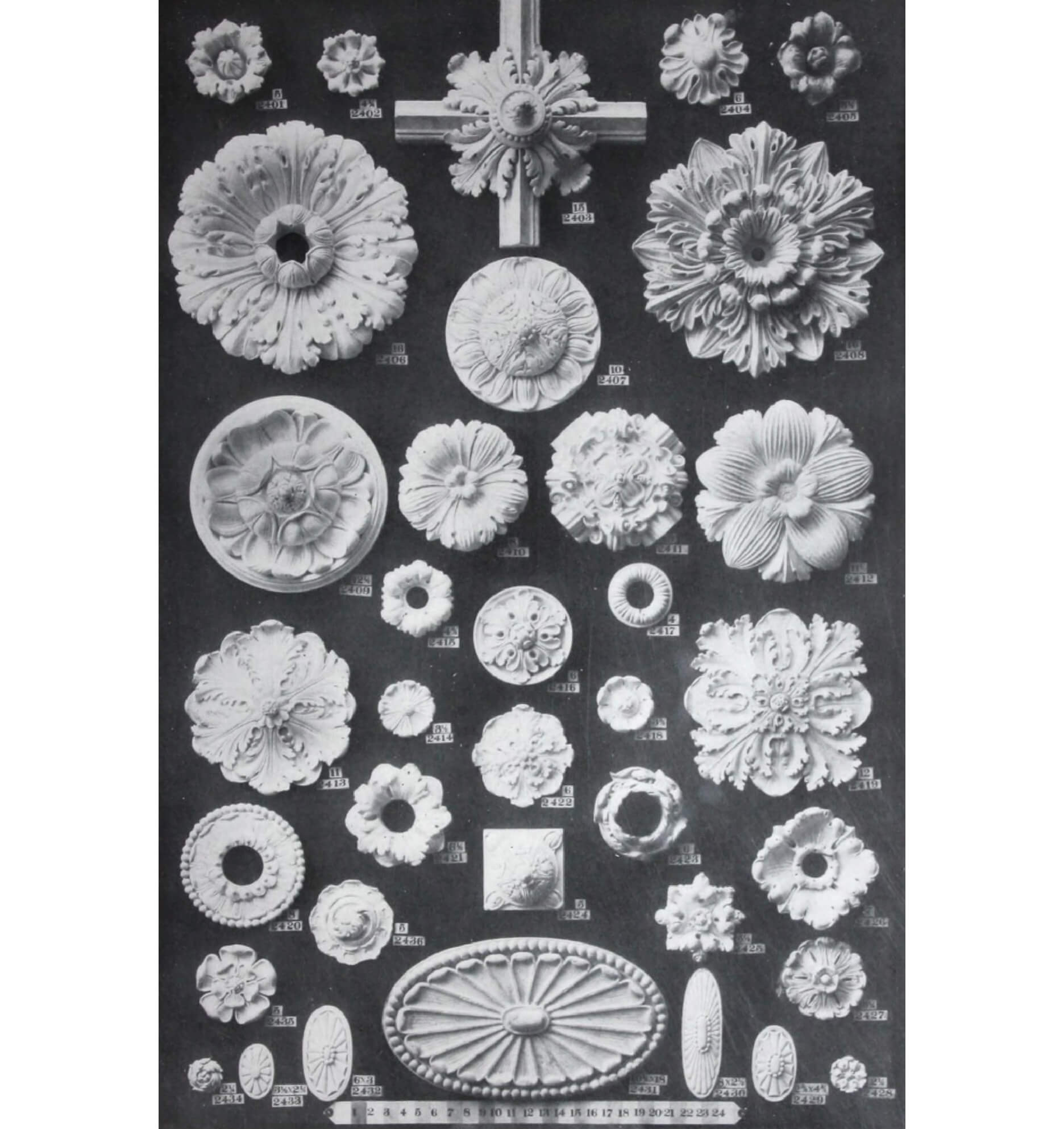

As one might expect, styles of medallions changed along with other interior fashions and are one of several clues to the age of a building. Greek Revival and Italianate medallions often employ leaf motifs. At their most simple, such a medallion might consist of leaves attached directly to the ceiling and radiating out from a rosette in the center. Plain-run moldings or beads might encircle the fanciful center decoration. Elaborate variations in homes of the well to do might be layered over bits of trellis or other background patterns and studded with blossoms. A medallion could be made entirely by hand on site, cast off site in a mold, or built up using a combination of methods.

In the late 19th century in Brooklyn, Neo-Grec medallions were typically made from molds in angular and asymmetric shapes, such as two stars superimposed on each other or a diamond fused with an oval. Ornamentation might include a mix of foliate and neoclassical motifs.

Subsequent Queen Anne-style medallions were somewhat more subdued and less exotic. Shapes could be round or square. Stylized and flattened leaf, flower, and vine patterns not unlike William Morris wallpapers were popular. A medallion for a smaller middle parlor might have a simpler all-over geometric pattern such as basketweave.

A return to neoclassical style toward the end of the century brought back Adams-style medallions in round and oval shapes with dentils, swags, stripes, and scrolls.

Whatever the era, typically medallions are centered in a room. They do not necessarily align with other elements, such as fireplaces, windows, doors, or the placement of medallions in other rooms. The meandering of medallions from room to room can be obscured by fretwork screens and pocket doors.

It is worth noting that parlors in grand Italianate brownstones of the 1860s and 1870s frequently feature elaborate plasterwork ceilings of which the medallion is an integral part. A pronounced cornice with heavy brackets typically anchors the ceiling. The ceiling is divided by panels surrounding an elaborate medallion, much like a fountain among planting beds in a formal parterre garden.

Medallions could be painted white or cream or polychromed. Similar to painted crown moldings, medallion colors were pale and soft, so as not to compete with the darker and weightier walls. Examples with original paint include survivors at the Linley Sambourne house in London and the Frank G. Edwards house in San Francisco. A round medallion in the parlor of the latter, designed in 1883 for a wallpaper and carpet importer, is painted primarily in shades of cream and deep cream, with delicate washes of melon and dots of terra-cotta that pick up stronger hues elsewhere in the room.

Broken, damaged, or missing plaster medallions can be repaired or replicated by a master plasterer. Stock medallions are available off the shelf in a variety of materials, although style options are limited. Before beginning any construction whose vibrations could damage existing plaster, such as cutting into walls for electrical rewiring, secure medallions and other ornamental plasterwork in place, ideally in consultation with a master plasterer. Later 19th century medallions often have openings big enough to admit a new electrical box without cracking or breaking, but earlier or delicate medallions may need expert handling to be successfully rewired to code.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- How to Get the Look: Victorian Bathroom Tile

- A Brief History of Decorative Painting in Brooklyn and Beyond/li>

- 10 Tips for Restoring a Wood Frame House in Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment