A Brief History of Decorative Painting in Brooklyn and Beyond

When the historic homes we live in and admire in Brooklyn today were spanking new, they were often enhanced with decorative painting.

A detail of an intricately painted door at Olana. Photo by Susan De Vries

When the historic homes we live in and admire in Brooklyn today were spanking new, they were often enhanced with decorative painting.

Special paint effects have a long history in the U.S., going back at least to the beginning of the 18th century, and continue to be popular today. Contrary to stereotypes, houses before and after independence were bursting with color and pattern. Dots and circles enlivened halls and kitchens, and painted scenes and trompe-l’œil vignettes covered paneling surrounding fireplaces in New England parlors, as Nina Fletcher Little’s “American Decorative Wall Painting” documents so well.

In the Victorian era, decorative painting moved away from scenes and freehand abstraction. During the Federal and Greek Revival periods in the first half of the 19th century, doors even in fine woods such as mahogany were faux grained, and floor cloths were painted to resemble marble. When Neo-Grec architecture came into fashion in the 1870s, stenciling, polychrome, geometric patterns and other decorative paint effects were popular, historic photographs and illustrations of interiors show. Entry halls, parlors and dining rooms were the most likely places to receive decorative paint treatments — often on plaster ceilings and wood ceiling beams.

In the late 19th century, paint effects were frequently designed to enhance the existing architecture by emphasizing panels on walls and ceilings or trim on cornices. Ceilings were divided into geometric shapes, sometimes around an oval center. Moldings and trims could be picked out in a variety of colors; geometric embellishments dotted beams; and vines, ribbons or abstract flourishes filled corners and panels.

Photographs, illustrations and written accounts of the day show decorative painting was common in upper- and middle-class homes — even in rental apartments. In a brownstone on the corner of Lee Avenue and Hewes Street in what is now south Williamsburg in 1888, a front bedroom was decorated in shades of blue, “with the ceiling frescoed to represent knotwork, in a mellow tone of blue, with a deep frieze of Japoniens” — probably a type of flower — an article, “Building Up Brooklyn: And Also Making the City Beautiful,” in the February 26, 1888 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle relates. In another house at 174 South 9th Street, the ceiling in the rear parlor was “frescoed to represent the four seasons, and the walls covered with silk plush extended over an ornamental molding.” Next door to 512 Bedford Avenue, a house had Lincrusta wainscotting in the hall, with side walls “in terra cotta, painted in fine stencil work. The ceilings are exquisitely frescoed in straw color to match.” Far away in a cottage at Mt. Vernon in Virginia, in a parlor “finished in old rose and silver,” the ceiling was “decorated with Colonial festoons, fuschias and a flight of swallows,” we read in the March 1895 issue of Scientific American.

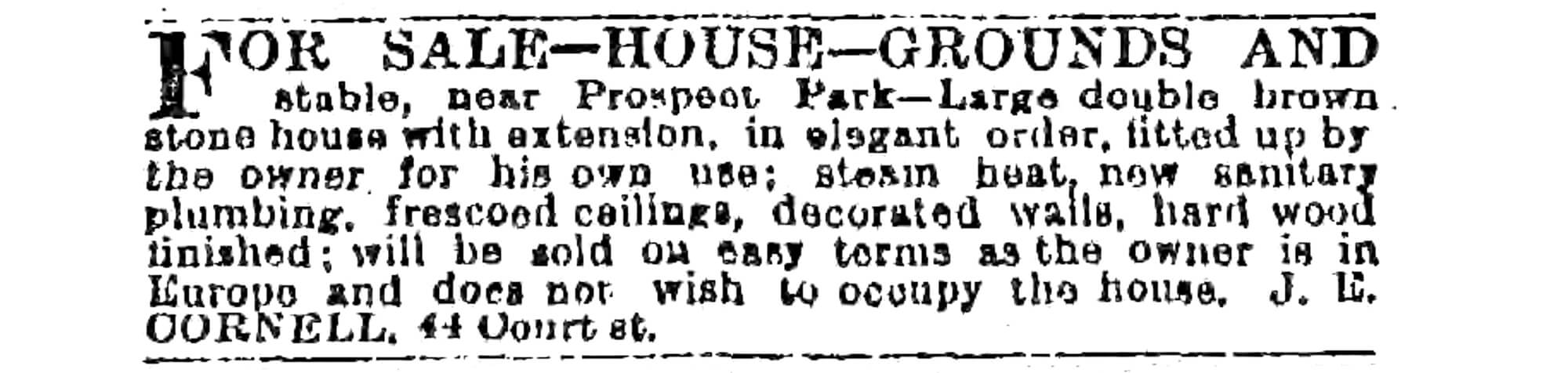

Ads for rentals frequently mention the apartments are “decorated.” An ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on October 25, 1895 went further and specified a flat at 308 Hicks Street in Brooklyn Heights had “frescoed ceilings” in addition to seven rooms, “cabinet mantels” and a dumbwaiter.

An elaborate but inexpensive wooden painted lady in what is now Bed Stuy had a colorful and highly patterned interior, traces of the original finishes show. Built as a two-family without central heating in 1895, it boasted a robin’s egg blue dining room with sugar pine woodwork faux painted to resemble oak. The rope-pattern picture-frame railings on the parlor floor were gilded and polychromed. The slate mantels of the coal fireplaces were ornamented with gilded incised decorations and painted to resemble marble.

Striking examples of original 19th century painted finishes can be found at Olana near Hudson, N.Y., Acorn Hall in Morristown, N.J., the Ebenezer Maxwell house in Philadelphia and, further afield, at the Linley Sambourne house in London and Wightwick Manor in Wolverhampton in England.

Designs on plaster were often executed in water-based paints such as calcimine and distemper; oil paints were favored for woodwork. Stenciling was useful for ceilings, which in the late 19th century were lighter than walls but seldom white, according to Roger W. Moss and Gail Caskey Winkler in “Victorian Interior Decoration.”

The cornice and trim could be picked out in a variety of soft colors, and paint manufacturers published many examples. Some decorating books proposed painting door panels and shutters with motifs such as vines and foliage; examples abound at the Linley Sambourne house.

The owner and creator of Olana, Hudson River School landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, favored oil paint on both woodwork and plaster. “Not a surprise for a master of the medium who made very little use of watercolor,” said William Coleman, Director of Collections and Exhibitions at The Olana Partnership.

Church hired sign and carriage painters to realize his complex designs, and colors were mixed under his direction from pigment, oil and turpentine.

Decorative paint styles changed over the years but remained popular well into the 20th century. In the 1980s and ‘90s, decorative paint effects from sponging to trompe l’oeil experienced a revival, spurred by Jocasta Innes’ book “Paint Magic” and the continuing influence of the late decorator John Fowler of Colefax and Fowler.

“While Olana and the interior ornament that defines its main house are certainly spectacular, Church was not alone in making use of patterned interior paint to evoke a mood,” said Coleman.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Brownstoner magazine. It was completed before the pandemic.

Related Stories

- Woodwork Restoration Secrets Revealed: How to Get That Nineteenth Century Glow

- Brownstone Bible Redux: Charles Lockwood’s Seminal New York Row House Book Gets an Update

- Lighting in the 19th Century Row House

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment