Schoolteacher’s Coup: Seeking an Integrated Neighborhood, a Couple Restores an 1899 House

Prospect-Lefferts Gardens was unusual when the duo first visited in 1974 and it remains unusual today because it is racially integrated.

Antiques and vibrant color set the tone in the parlor. Photo by Lesley Unruh

Prospect-Lefferts Gardens was unusual when Elaine and Bob first visited in 1974 and it remains unusual today because it is racially integrated. “Saul Alinksy said integration is the brief period between when the first Black people move to a neighborhood and the last white people move out,” said Bob, quoting the famous activist. “That didn’t happen here.”

They were looking for just such a neighborhood and an old house to live in when they accidentally stumbled on the area. One weekend they had been planning to go on a drive in the country but it rained so they went on a house tour in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens instead. They were pleasantly surprised to find marvelously intact homes with historic details and appealing layouts as well as a stable, integrated community.

“We had never seen a brownstone that didn’t have a long hallway,” said Elaine. (The couple asked that only their first names be used.) “These were the first modern homes that took advantage of central heating and didn’t have to close off rooms,” added Bob. The tour was in June, and by October they had closed on a house.

Made of brick and stone with a bay and round-arched windows, the 1899 Romanesque Revival/Neo-Renaissance home was neglected but intact when they bought it from an out-of-town relative of the previous occupants, who’d lived there since the 1920s. Although unoccupied, it was completely furnished.

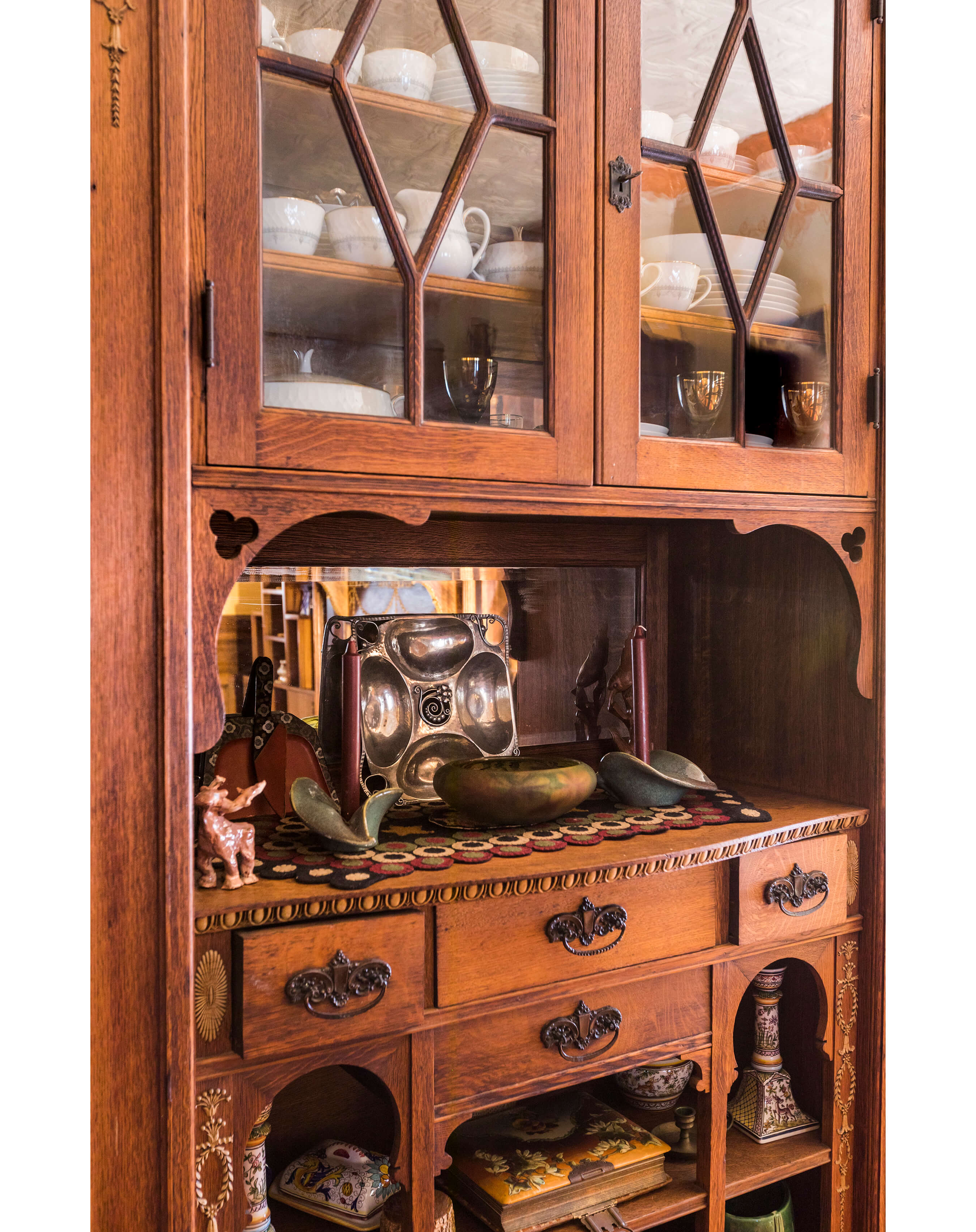

“We crossed out ‘broom swept’ on the contract of sale and told them they could leave anything they wanted, so there was a lot of junk and papers but they left a lot of nice pieces,” said Bob. Finds included a sideboard in the dining room, a library table in the middle parlor, light fixtures and even some jewelry.

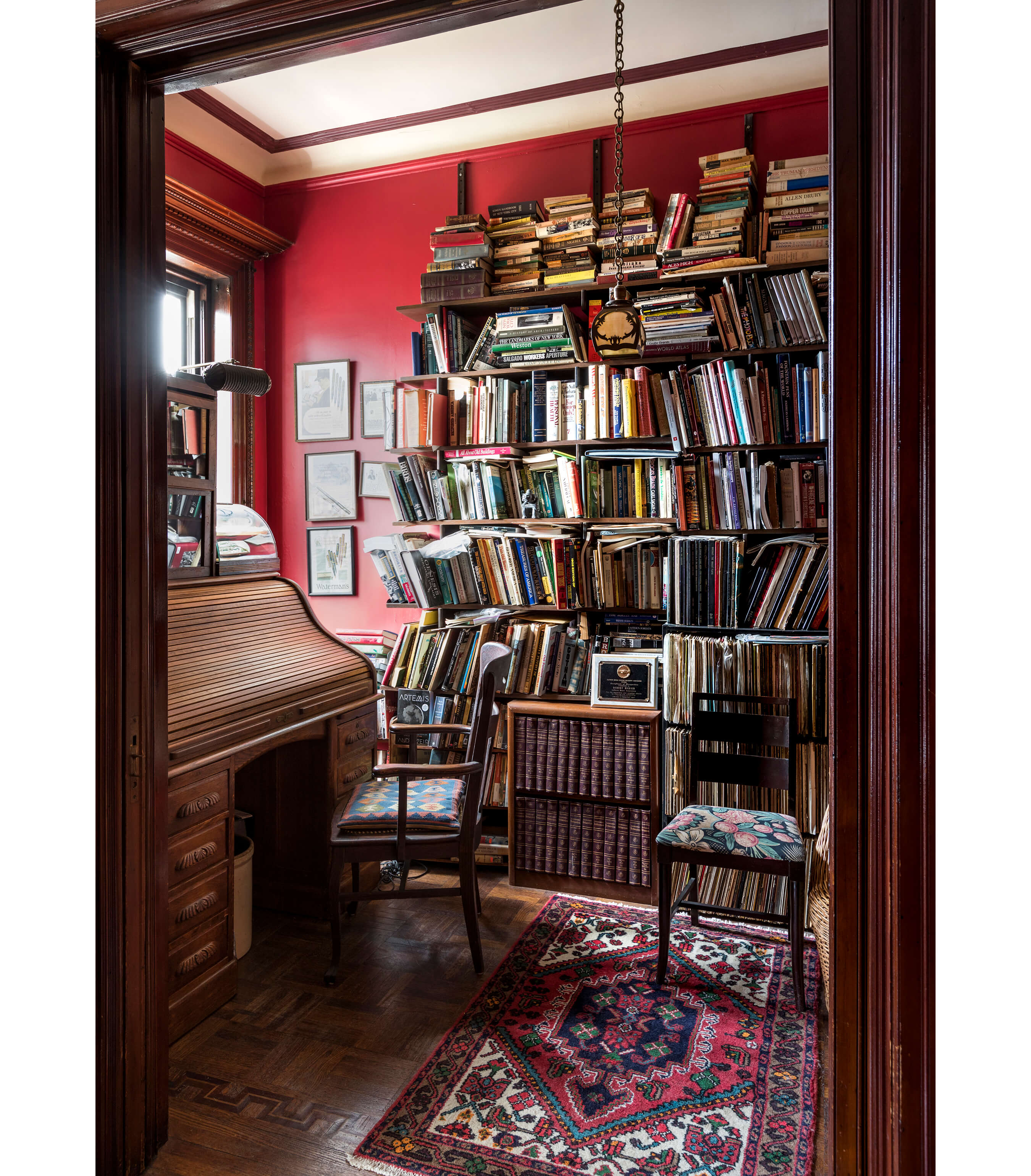

The three-story, single-family house has an expansive parlor floor with all manner of woodwork, including a coffered ceiling, and fireplaces with colorful tile spread over its three parlors and library. Upstairs among the bedrooms is a well-preserved bathroom with a skylight, original tile, claw-foot tub and handsome 1910 pedestal sink.

On the garden floor is a well-appointed dining room with paneling and a built-in sideboard. The kitchen, in the rear overlooking the garden, was little changed when they first saw it, with a built-in dish cupboard and a row of deep soapstone laundry sinks. As most Brooklyn row houses of its era have, out back was a shed with a dubious foundation and a tiny room with a toilet but no sink. “It was really literally a dirty hole,” Elaine said.

They put in new wiring and plumbing, painted and gently updated the kitchen. The wallpaper in the parlor had turned brown and had to be removed, and “all the appliances were in the dining room” while the work went on, Elaine recalled. The three soapstone tubs were repurposed as steps in the garden.

One day while stripping paint, Elaine accidentally got paint remover in her eye — and the plumber had turned off the water. Luckily, there was an eye doctor close by, a remnant from when the stretch was known as “doctor’s row.” She ran down the street with a neighbor’s help, and the doctor was able to save Elaine’s vision.

They decorated with antiques. “Obviously we represent an earlier generation of brownstoner,” explained Bob. “But people furnished with antiques” — not mid-century modern — “partly because they were less expensive than other options. Prices were low, and we didn’t have to worry about fakes.”

Said Elaine: “We wanted to be true of the spirit of the house.”

The plan was the house should look like it had been owned by the same family for generations “and we kind of stopped in the 1930s,” Bob said.

What did their parents think of the new place? They both laughed.

“They thought it was terrible,” said Bob. “Our first apartment, remember what my mother called it? ‘That filthy basement slum.’” When the couple bought the Victorian loveseat now in their parlor during a vacation in Vermont, “my mother said, ‘it’s so old fashioned,’” he remembered.

At the time, it was conventional to aspire to move to a new house in the suburbs, and lending encouraged whites to do exactly that. Prices of townhouses in Brooklyn were low but it was difficult to get a mortgage. Lenders were few and most of Brooklyn was redlined. The couple had to put down 40 percent, and the resulting monthly mortgage payments were about the same as their rent on a floor-through apartment in a brownstone in south Park Slope.

This is what the late preservationist Everett Ortner called the “schoolteacher’s coup” — the idea that “two schoolteachers could buy an old house and live almost like millionaires on almost no money,” said Bob. Elaine was working as a schoolteacher and Bob, who studied political science, was working for the city in personnel.

Soon after they moved to Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, Bob took a class at the New School with Ortner, a cofounder of the Brownstoner Revival Coalition, which defended historic townhouses and neighborhoods from the threats of neglect and demolition. Ortner urged attendees to promote their neighborhoods and not to “hide their light under a bushel,” as Bob recalled.

Bob, originally from Forest Hills in Queens, and Elaine, who is from East Flatbush, met at a theater party organized by a friend in 1968 and married in 1970. White and Jewish, they were turned off by the racist and anti-semitic attitudes they encountered in south Park Slope, where they were living in the brownstone apartment.

When they happened on Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, it was about 20 or 25 percent white. They liked that the neighborhood was integrated and whites were not moving out as Blacks arrived. It had been integrated decades earlier as Black professionals such as doctors, lawyers and university presidents moved in. In 1968, locals formed a neighborhood group, the Prospect-Lefferts Garden Neighborhood Association, or PLGNA, whose purpose was to attract people of all races to the area.

Taking Ortner’s suggestion to heart, over the years Bob has been active with a variety of neighborhood groups (including PLGNA, Lefferts Manor Association, Community Board 9 and PLG Arts), helping to put on the yearly house tours, landmark the neighborhood, and promote community cohesion through events such as exhibits and concerts.

The 1979 designation report noted “Prospect Lefferts Gardens always has been a well cared for and stable community…Today the district is one of the few successfully integrated middle-class communities in New York City. The row houses of the neighborhood did not see the post-war decline of many of Brooklyn’s brownstone areas.”

It’s a great source of neighborhood pride that residents intentionally fought for integration and it has lasted, Bob recently noted in Voices of Lefferts, a neighborhood journal.

“Racism is detrimental to everyone, including white people,” said Bob. “Most white people who have racist attitudes do so out of ignorance and fear and I think the only way to counter that is to live with other people who are different than you.”

He rues the high prices and displacement that what he terms “corporate hyper gentrification” has brought in recent years and said he hopes the neighborhood will be able to stay racially and economically diverse.

The couple traveled widely before they had their son, and both enjoy collecting antiques. Skiing, camping, visiting Vermont and trying new restaurants are some of their interests. Bob, a passionate preservationist, belonged to a Prospect Park running group until recently, and is a photographer.

The house has a ghost story. “I don’t believe in ghosts,” said Bob. The neighborhood had been “ultra safe” but after the 1977 blackout, “there was a big increase in crime city wide. So we got an alarm. It was a real pain to use,” and lightning storms would set it off. One night the alarm sounded, and when Bob and Elaine went downstairs to investigate, they discovered their beer steins on the rear parlor mantel were not in their usual places. The family that had lived there before was German, so “we figured it was one of the sisters moving the steins around,” said Bob.

When muggings increased in the area in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, one of the neighborhood associations formed a private security service funded by subscriptions to drive people to and from the subway. It was effective and disbanded in the early ‘90s when it was no longer needed.

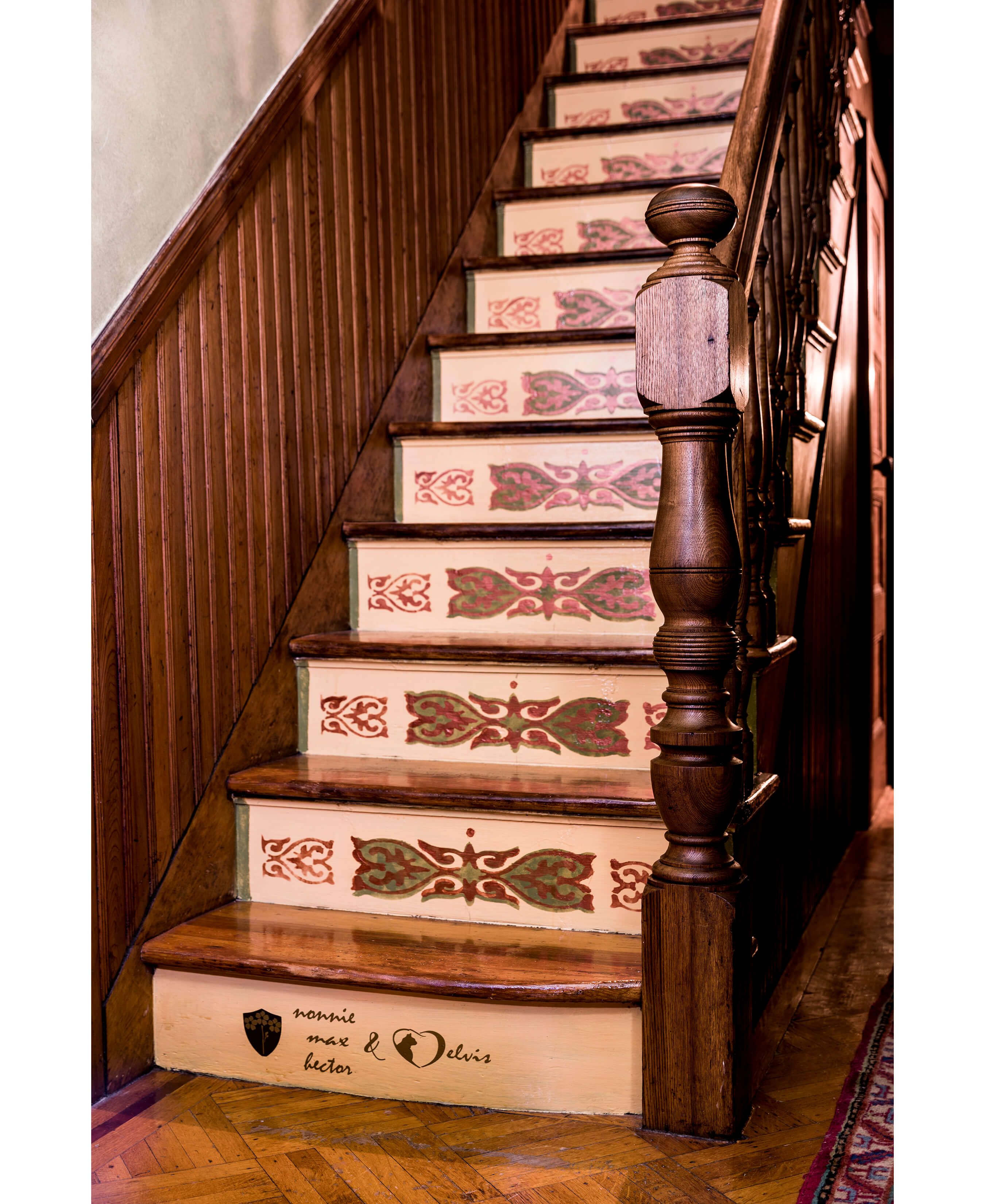

The couple has been slowly renovating over almost 50 years. Recent updates include skim coating plaster, updating the kitchen with a new floor and stove hood and, lately, decorative painting.

When one of the early electric etched glass acorn shades for the coffered ceiling in the middle parlor broke, they found a glassblower in Prague via Etsy to reproduce early 20th century art glass shades.

The house’s coved ceilings lend themselves to decorative painting, which was something they had seen and admired in mansions and on house tours over the years. “The spirit is similar to what would have been done in Victorian times but it’s not quite the same,” said Elaine. They started with a sky and hummingbird in the front parlor. For decades, the staircase had an unstripped patch and no runner, and decorative painter Ingrid Van Shipley came up with the idea to cover it with a painted design and add the names of all their cats.

Throughout the house, splashes of color connect objects, architectural features such as mantels, and painted surfaces. The house has been on the local tour five times.

They have asked Van Shipley, whom they met on the Bed Stuy house tour, to come back and add birds. “She just added a blue jay. She doesn’t know it yet, but she’s coming back to do a robin. We’re doing all the local birds,” said Elaine.

[Photos by Lesley Unruh | Styling by Heather Greene]

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Brownstoner magazine. It was completed before the pandemic.

Related Stories

- Going Back Home: Artist Paul Sue-Pat Brings Life to a Bed Stuy Townhouse

- Creative Life: Family and Community Inspire Bed Stuy’s Kai Avent-deLeon

- Fun and Games: Wall-to-Wall Art, Vibrant Color Set Brooklyn Heights Townhouse Apart From the Rest

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment