Going Back Home: Artist Paul Sue-Pat Brings Life to a Bed Stuy Townhouse

In art and life, a painter and sculptor looks to the past to inform the present in Bed Stuy.

A Confluences modular sofa by Philippe Nigro for Ligne Roset and bright red Olivetti typewriter by Ettore Sottsass lend a pop art luster to the den

When Paul Sue-Pat first came to Bed Stuy, he wasn’t sure he liked the neighborhood. Born in Kingston, Jamaica, he had arrived in New York after stops in London, Miami, and Connecticut with dreams of becoming an artist. His small studio was located on the first floor of a building on West 4th Street in Manhattan; the rent was $200 a month. He was struggling but happy, scraping out a living. But when the building was sold, the new owners wanted him and the other artists who had studio space there to move out. When the landlord came with what Sue-Pat calls a “bag of cash,” he decided to follow the advice of some artist friends and move to Brooklyn. “I took the money and ran,” he said with a laugh.

Dumbo was a consideration and, later, Williamsburg. But Sue-Pat found the prices too high. Bed Stuy was suggested, but when he went there he found it too recognizable. “It reminded me a little of Kingston,” he remembers. “It felt like home.” This wasn’t something he necessarily wanted. He left home for a reason. But something kept drawing him back to Bed Stuy. Eventually, he found a space on a quiet cul-de-sac, which he still uses both as a studio and exhibition space, and later a brick row house a few blocks away where he and his partner, an emergency medicine physician, would settle.

Moving to Bed Stuy helped solidify his artistic practice. “For a long time, I thought, ‘Am I a painter? Am I a sculptor?’ It turns out I’m everything,” he said. “I learned to embrace it all. I don’t want to fight it. I just want to create.”

In both work and life, creativity is at the forefront for Sue-Pat. And to bring that creativity forward, he needed to find a place that matched his new conception of home. When he first looked at the row house, a fire had destroyed large parts of the interior. A lot of work needed to be done. “It was empty; there was nothing here,” Sue-Pat said. “I had the feeling that it needed somebody to love it.” He immediately began to see it like a canvas, where his creative impulses could run free. And when he peered through the boarded-up back windows, he noticed the lush backyard. It had elements of the natural world, which reminded him of his childhood and also presented new opportunities to express himself. Home was not just something new but the accumulation of life’s experiences up to that point.

It was a long journey to this moment. Sue-Pat first became interested in art as a child in Jamaica. His mother tells a story about how he once, at around the age of 10, removed all the furniture from his bedroom and replaced it with rocks. It was his first sculptural installation. Later, inspired by his grandmother, he started making little objects and selling them at a local market with his grandmother, who made flowers. But the atmosphere in Jamaica at that time made the possibility of exploring an artistic life nearly impossible. “I stood out, I was an odd fit,” Sue-Pat said. “I was lighter skinned, and was considered very rich even though I wasn’t. It was difficult to go anywhere.” After getting in fights at the public school he was attending, Sue-Pat was shipped off to a “posh school,” he said, which opened his mind to possibilities away from home.

He later attended the Edna Manley School of Art in Jamaica, which, he said, finally solidified in his mind that making art was what he wanted to do. Where that was going to happen, though, was still up in the air. That is, until he was forced to leave his home. “I had to run,” Sue-Pat said about his sudden departure from the place where he had grown up. “I had some issues in Jamaica that made me flee literally in the middle of the night.” He tried to get to London, where he would later briefly live, but couldn’t afford the ticket. Because one of his sisters lived in Miami, he decided to go there and stay with her for a while. “But I really wanted to go to New York,” he adds.

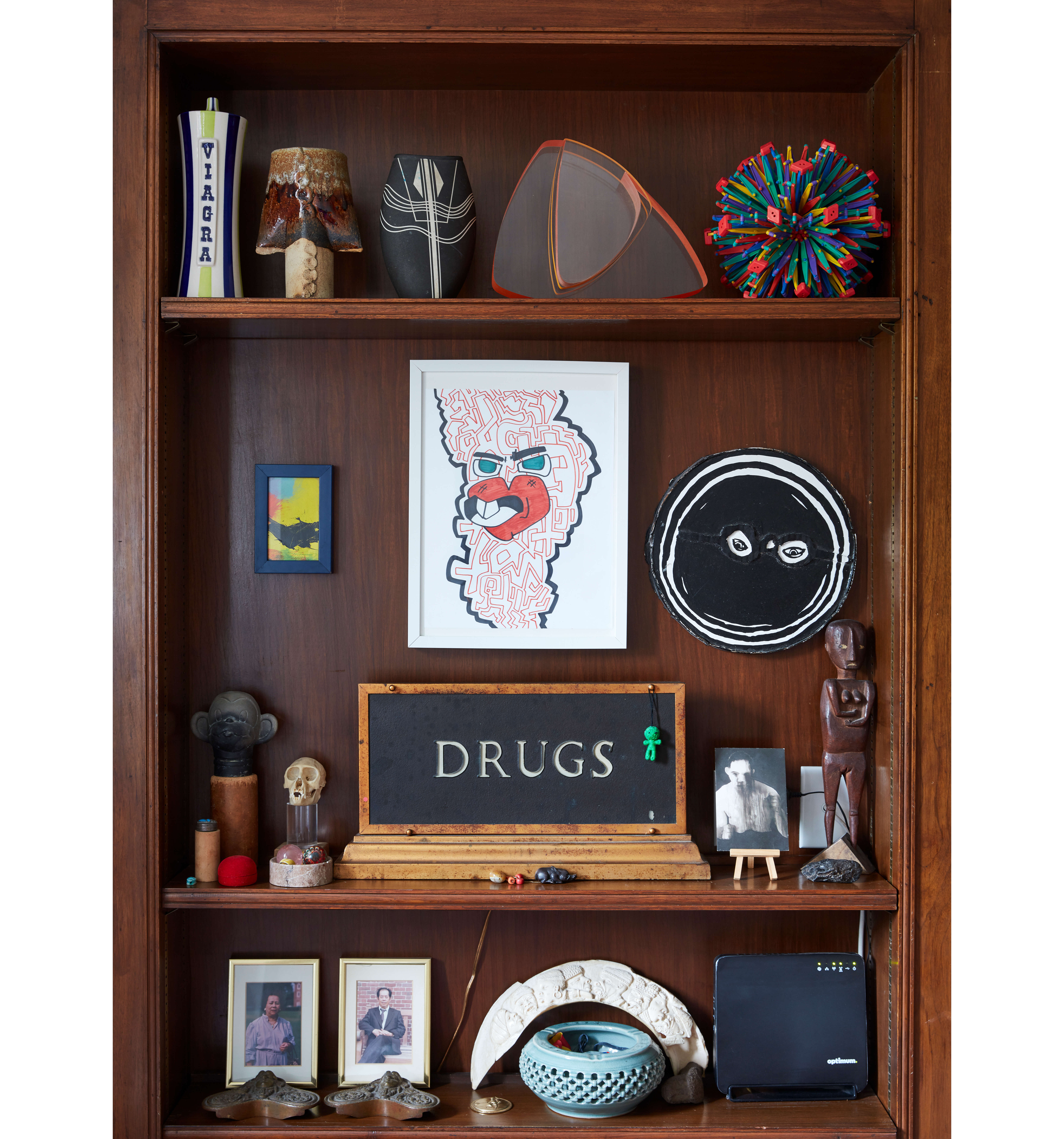

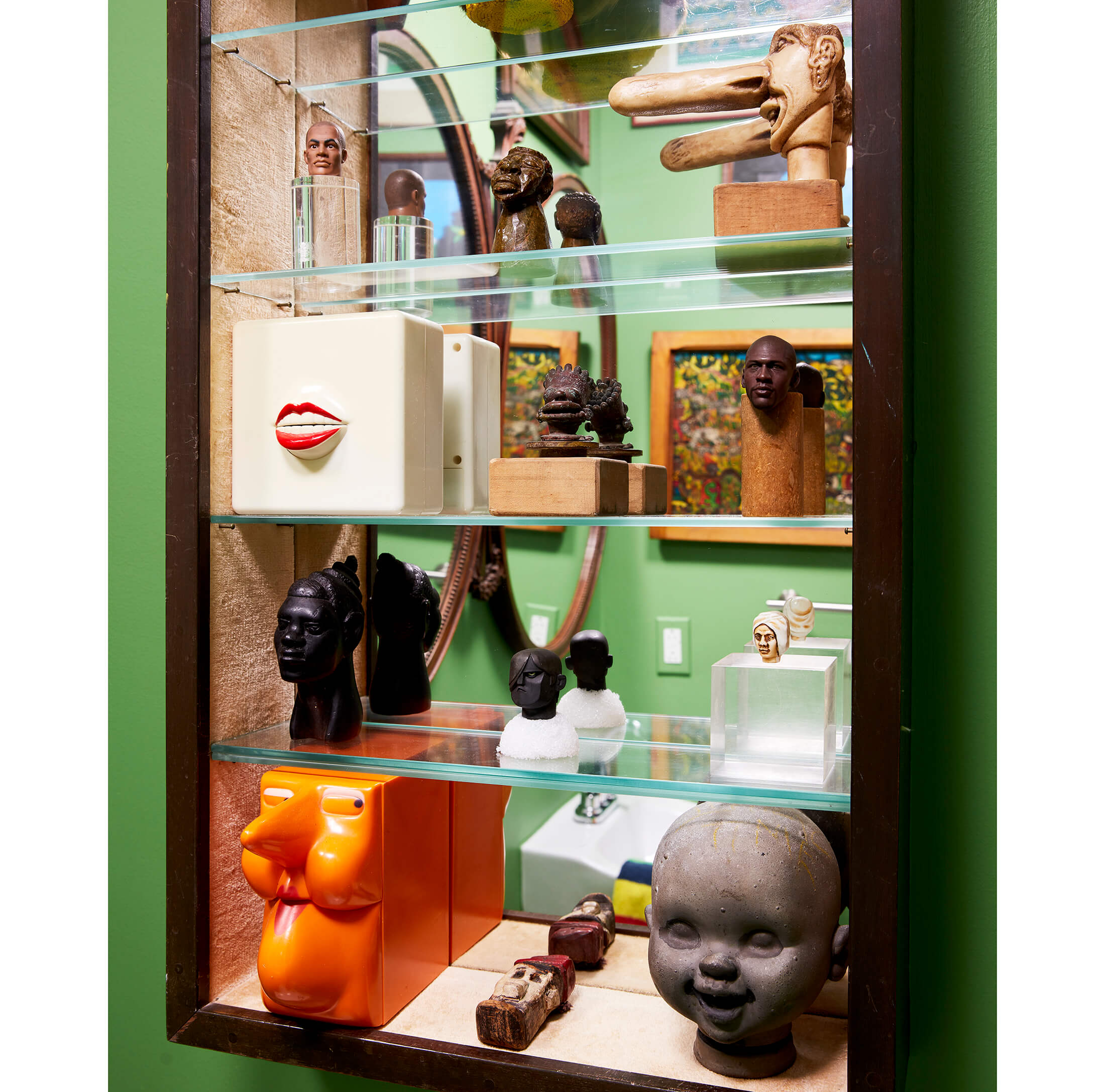

Soon enough he would get here. Crashing with his godparents — who happened to be connoisseurs of Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, and WPA art and own a gallery in the West Village — was his introduction to the city’s art world. He ended up living with them for almost six years. Their influence can be seen directly in one of the house’s rooms, which serves, in a way, as a tribute to their interests. Many of the objects from their home that Sue-Pat inherited after they passed away reside here. “They were gracious to take me in and show me a different world,” Sue-Pat said of his godparents. “That was my first real New York experience.”

That experience would go on to influence his renovation. Most of the initial work on the house was on the parlor floor, where the most damage existed. “I try not to think of problems as problems. I think problems create creativity,” Sue-Pat said. He had been collecting both furniture and design objects for years, often picking them up for cheap at flea markets and estate sales, and also random items he sometimes incorporated into his sculptures. So when considering pocket doors at the entrance of the parlor during the initial renovation, for instance, Sue-Pat decided to put two giant columns painted sky blue that were stored in his studio in the open space instead. His interest in texture, a major component of his paintings and sculptures, led him to leave much of the original banister in the house intact, even the parts that had sustained fire damage. “We thought it would be nice to remember part of what was here before,” he said.

One of his favorite parts of the house is the outdoor area that sparked his imagination during his first visit. He was interested in the ways he could make it feel like the Blue Mountains, a cooler, lush part of Jamaica and a place from his childhood he remembers fondly. “I knew it had to be something I could escape into,” he said. So, in addition to filling the yard with opulent plants and a variety of sculptures, he turned the windows in the back of the house into doors and created an enclosed deck off the parlor floor. “I’ve always been in love with having a British solarium,” he said. “This was a cheaper version of that.”

“I wanted it to look effortless,” he added. “I didn’t want things to look forced. People come and think I’ve lived here for many, many years.”

There is a certain lived-in quality to the work Sue-Pat makes in the studio as well. When he has an idea, he said, he is “open to the idea changing.” Sculptures that look one way will change form once they have been placed in a certain context. Nothing is static. Sometimes an idea for a sculpture will become a painting or vice versa. Many of his recent pieces, which were exhibited in his studio-gallery space last year, also find Sue-Pat reinvestigating memories from his childhood. There are sculptures, he said, modeled after his grandmother. A giant shoe filled with insects came from his boyhood fear of ants in Jamaica. “I’ve never done this kind of work, that presents nature and where I grew up,” he said. “I’ve always run away from that. I think of it as a rebirth, going back to my roots.”

To go back home, he needed to discover what that meant to him in Bed Stuy. “I was always trying to find home, my space, my people,” Sue-Pat said. “In New York, you can come from anywhere, find your own space, and reinvent yourself. I wanted to become what I wanted to be.”

[Photos by David A. Land | Styling by Liz MacLennan]

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 issue of Brownstoner magazine. It was completed before the pandemic.

Related Stories

- Creative Life: Family and Community Inspire Bed Stuy’s Kai Avent-deLeon

- Fun and Games: Wall-to-Wall Art, Vibrant Color Set Brooklyn Heights Townhouse Apart From the Rest

- Designer Malene Barnett Goes Full Spectrum With Color in Her Bed Stuy House

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment