Walkabout: Professor Friend and the Electric Sugar Factory, Part 3

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story. The dawn of 1889 began with a small financial panic as hundreds; perhaps thousands of investors, both in New York and in England began to realize that they had been taken for fools. Whether through basic greed, misinformation or just blind faith, they had…

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story.

The dawn of 1889 began with a small financial panic as hundreds; perhaps thousands of investors, both in New York and in England began to realize that they had been taken for fools.

Whether through basic greed, misinformation or just blind faith, they had invested their money in a company that was a complete scam.

The Electric Sugar Refinery Company, through its owners and managers, boasted that it could take raw sugar and turn it into pure refined sugar, bypassing all of the time consuming and expensive methods used at that time by every sugar refiner in the world.

Through the use of a super-secret electric method of refining sugar, invented by an eccentric inventor named Professor Friend, the company told its investors that they would make themselves and everyone connected with them very rich.

In truth, they had only made the owners of the company rich – namely the inventor, his wife, her step-father and his wife. When the death of the Professor meant they couldn’t sustain the con game anymore, the remaining people took the money and headed for parts unknown, leaving behind an empty factory and emptier wallets.

Parts One and Part Two our story give more details of Professor Friend, his wife Olive, and her step-father and mother, the Reverend William Howard and his wife, Emily.

We also learn about the president of the Electric Sugar Refining Company; an Englishman named Cotterill, and the Secretary/Treasurer, another Englishman named Robertson. They were responsible for getting the ESRC in the British press, and gathering hundreds of people in England to invest, both rich and poor.

We also learned about the machine whose use prompted so many to open their wallets and donate, as if they had seen a miracle in the making. Perhaps that was the worst of it. Many of the investors, especially in England, were pious religious people who had followed men of faith, and been duped.

In New York, it wasn’t so much God that moved investors, it was money. Faith and money, a dangerous combination sometimes, and in this case a faith shattered when the inventor of the machine, Professor Friend, suddenly died, in 1888. His passing shattered the carefully crafted operation, and exposed the empty core within.

Professor Friend died in the winter of 1888, during the Great Blizzard. His death shattered the trust of investors, and caused them to finally open their eyes.

By the first week of January, 1889, Olive Friend and her parents had packed up and taken off for parts unknown, leaving a large empty factory building and a company president and secretary-treasurer to face angry investors.

Were they in on the scam too? Investigators, reporters and investors wanted to know. They also wanted someone to pay dearly. It seemed highly unlikely that the two of them didn’t have a clue.

William H. Cotterill, the president of the ESRC, looked like a biblical patriarch. He was sixty years old, about six feet tall, and balding, with only fringe of hair around the back and sides of his head.

But he had a very full grey beard that fell a foot onto his ample chest, and a thick mustache that grew from his upper lip to join the beard. He also had a pair of piercing eyes that gleamed below thick grey eyebrows, accompanied by a prominent nose.

When he gave his first press conference after the scandal broke, on January 11, 1889, those eyes flashed at the reporters and investigators waiting to hear what he had to say.

When the conspirators had disappeared, he had disappeared for a while as well. Naturally, everyone assumed that he had taken off with them.

But he was back, telling reporters that he had been as fooled as everyone else. He stood before them in a modestly priced suit, and spoke with his soothing English accent and the manner of a pious and sorrowful grandfather who had to tell his loving grandchildren some bad news. And the news was bad, really bad.

“As you can see,” he told the crowd, “I am back. I came to face the music.” He stood next to Mr. Robinson, who didn’t look quite as calm, or as ready to face anyone.

They were all in the empty factory in Red Hook, where the sugar was to be refined. He went on to tell them that he had gone to Michigan, where it was believed Mrs. Friend and her parents were staying.

When reporters asked if he had seen Olive, and more importantly, did he have the secret formula, he sadly shook his head, and said that the three were no longer in Ann Arbor, but had fled to Canada, beyond his reach.

There were still those who clung to the hope that the secret formula really existed, even now, and apparently Cotterill was one of them. Or so he acted.

One of the reporters asked him about recent allegations that he had cheated clients out of money before, in his former business as a maritime lawyer and go-between for English ex-pats in Manhattan.

Cotterill dismissed those queries, called the allegations lies, and pointed to a group of barrels packed into a corner of the room.

“See those?” he said. “Those barrels contain some of the finest refined sugar in the world, and they came from the Professor and his invention.” “So what is the process?” asked a reporter, “Where is the machine?”

Cotterill turned and smiled at them, “I’ve said too much,” he said, “I’ll be making other statements later.” He then dismissed the crowd. A very distraught Mr. Robinson trailed after him.

A day or two later, Secretary-Treasurer Robinson faced the press himself. He told reporters that Mr. Cotterill had just told him about the case against Professor Friend in Chicago, back in the 1870s.

At that time, an investor had alleged that he had been swindled by the professor into investing heavily in an invention that did not exist. The case had been thrown out on a technicality, but was alarmingly familiar. Robinson was shocked and dismayed.

He also told reporters that he had also learned of Cotterill’s old case, where he had been accused to mishandling his client’s funds. He was equally shocked and dismayed that he had been surrounded by people who kept important secrets. As a godly man, he found himself surrounded by those who were not who they said they were.

When asked if he thought the secret formula was really a scam, Robinson skated. He told them that he had seen boxes of equipment and machine parts being delivered to the factory.

He said that the company had collected over $450,000, but a lot of that went into buying the factory and hiring workers, the architect and for salaries and equipment. When asked if he had actually seen this equipment out of the crates and set up, he said no.

The nature of his agreement with the Professor was that he would not be privy to the secret formula or the machine, so he never looked in the crates or boxes.

As he spoke, the realization of his gullibility and trust overwhelmed him. He began to choke up, realizing that he had been one of the company’s largest investors, and he had talked his wealthy relatives into investing, as well as his church.

He was a high ranking member of a British religious sect called the Christadelphians, and they had trusted him and invested heavily. Many of the poorest members had pooled together to buy some stock, and they too, were going to lose everything.

Reporters asked if he thought the Queen’s Bench would be instigating an investigation on behalf of British investors, and whether or not the Crown would be coming after him.

He did not know. He did know that warrants had been issued for Olive Friend and Rev. and Mrs. Howard. He hoped the entire thing would be over soon, and the truth of the machine, the money, and the company would be out in the open once and for all.

The police arrested Olive and the Howards in February of 1889. New York investigators came out and searched Olive’s house looking for the formula. The trio was brought into court in Ann Arbor to face charges of obtaining money under false pretenses.

They also faced charges for having accepted money from local Michigan investors through mortgages on properties purchased by ill-gotten gains.

The police and district attorneys in Michigan had been very secretive and careful about approaching the trio. They did not announce that they were conducting an investigation, even though the story of the fraud had followed them to the Midwest.

They had people watching them, and eventually Olive and her mother relaxed and began spending money. Rev. Howard was much more cautious, and was staying in Canada. There was a civil case pending, regarding the mortgages, but he wasn’t worried, because he stayed out of reach.

There was no talk of a criminal charge. When nothing happened, and no police came to the door, Howard was sure that they had forgotten about him.

He came back across the border to Milan, Michigan, near Ann Arbor, where they were living. When the police were sure he was there, they swooped in and made the arrests.

Two other people were arrested with them, charged as accessories after the fact. They stayed in jail in Michigan. After charges were filed in Michigan, the trio was extradited back to New York.

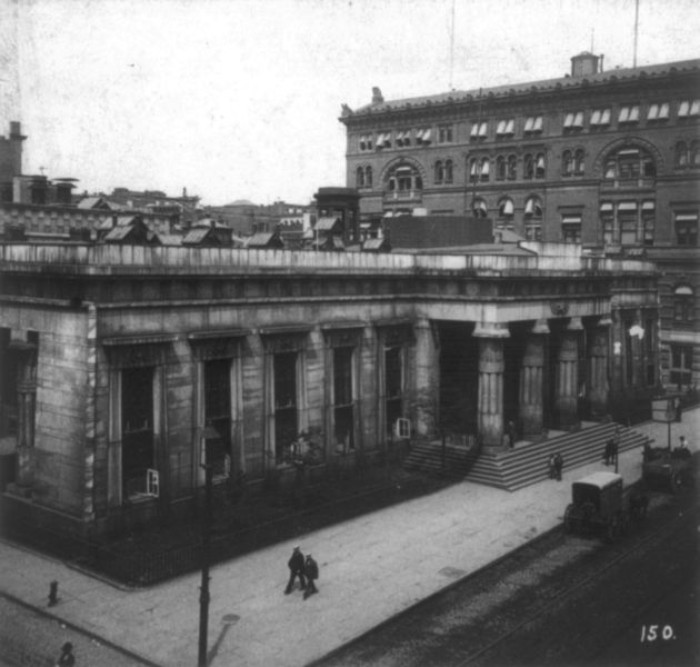

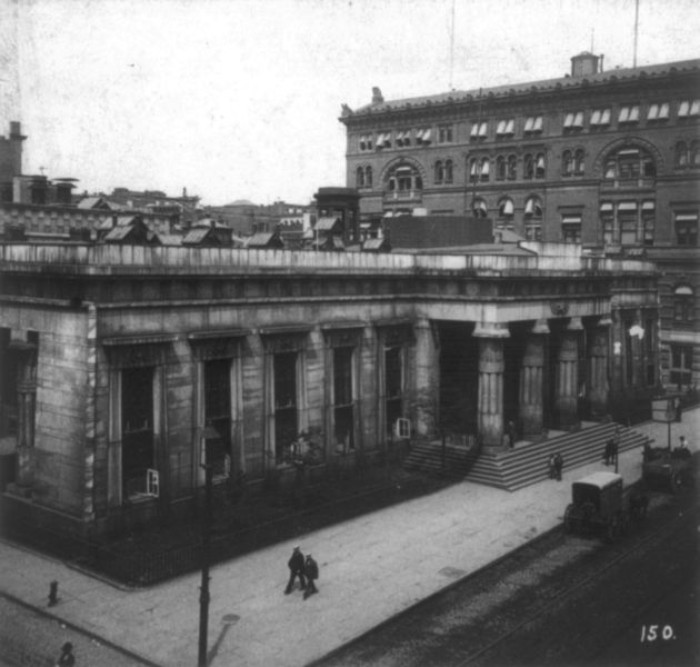

Olive was in the Tombs prison in lower Manhattan. She vigorously proclaimed her innocence to reporters, but was unable to raise the $7,000 bail, and stayed in jail for some time.

She also sued the Sheriff in Michigan for invading her privacy and removing a trunk from her home when she was arrested. That trunk had been turned over to investigators. Court papers show that she insisted that the secret formula for sugar refining had been in the trunk.

The formula had been in a notebook, written with a cypher that her late husband had only shared with her and with her step-father. No one else could decode it.

The courts sided with her, and ordered the trunk and its contents to be returned. There was no mention in the press as to whether or not there really was a notebook, or what it contained.

Olive Friend, Emily and Rev. Howard were all in jail, with a trial coming up. The entire financial community, and probably half of England were waiting to see what would happen next. The truth would finally have to come out. Was there a secret formula? (They still couldn’t let go of that.) How did the machine work, and was the Electric Sugar Refinery the rip-off of the century? Most importantly, would anyone get their money back? It looked especially bad for the small, foreign investors who had to stand in line behind the big money men. If little or no money could be recovered, what kind of harsh sentences could be imposed if they were found guilty? We’ll find out next time, as the trial begins.

(Photo:Tombs Prison in Manhattan (first of four Tombs buildings, btw) Source:nyc-architecture.com)

As good old Teddy Havemeyer said: “Never buy a pig in a bag.”