Bridging Nature With New Technology: The Cleft Ridge Span of Prospect Park

At first glance, casual strollers may not realize they are walking underneath something quite unusual in Prospect Park.

The bridge circa 1894. Photo via Prospect Park Archives

At first glance, casual strollers may not realize they are walking underneath something quite unusual in Prospect Park. Perhaps they notice a distinct character in the Cleft Ridge Span but assume the softly colored decorative detail arching gracefully above them is the result of delicate tile work or terra cotta ornamentation.

That would be incorrect — the bridge, nestled just south of the boathouse, was actually a technological experiment by the park’s designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, an effort to keep costs low without sacrificing artistic vision.

Like the other bridges in the park, the Cleft Ridge Span was designed to allow pedestrians to safely amble along the scenic walkways, out of the path of the carriages which passed on the route overhead.

The bridge was intended to be built of brick or granite but, according to Olmsted and Vaux’s 1872 report to the Commissioners of Prospect Park, before work was begun it was decided that using a new material “would allow of a considerable increase of artistic character in the details of the design without additional cost.”

That new material was cast concrete, or artificial stone, known as Béton Coignet and named after the French inventor Francois Coignet who experimented with the material and patented his own formulas. His particular recipe called for a carefully measured mix of lime, sand, gravel, cement and water to be layered into molds.

Olmsted and Vaux collaborated with John C. Goodridge of the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company to adapt the original bridge design for the new material. Construction on the span began in the fall of 1871 and was completed early in 1872.

The stone company, founded in 1869, would complete their own impressive project in 1872 — construction of their all-concrete showroom and office at 360 3rd Avenue in Gowanus.

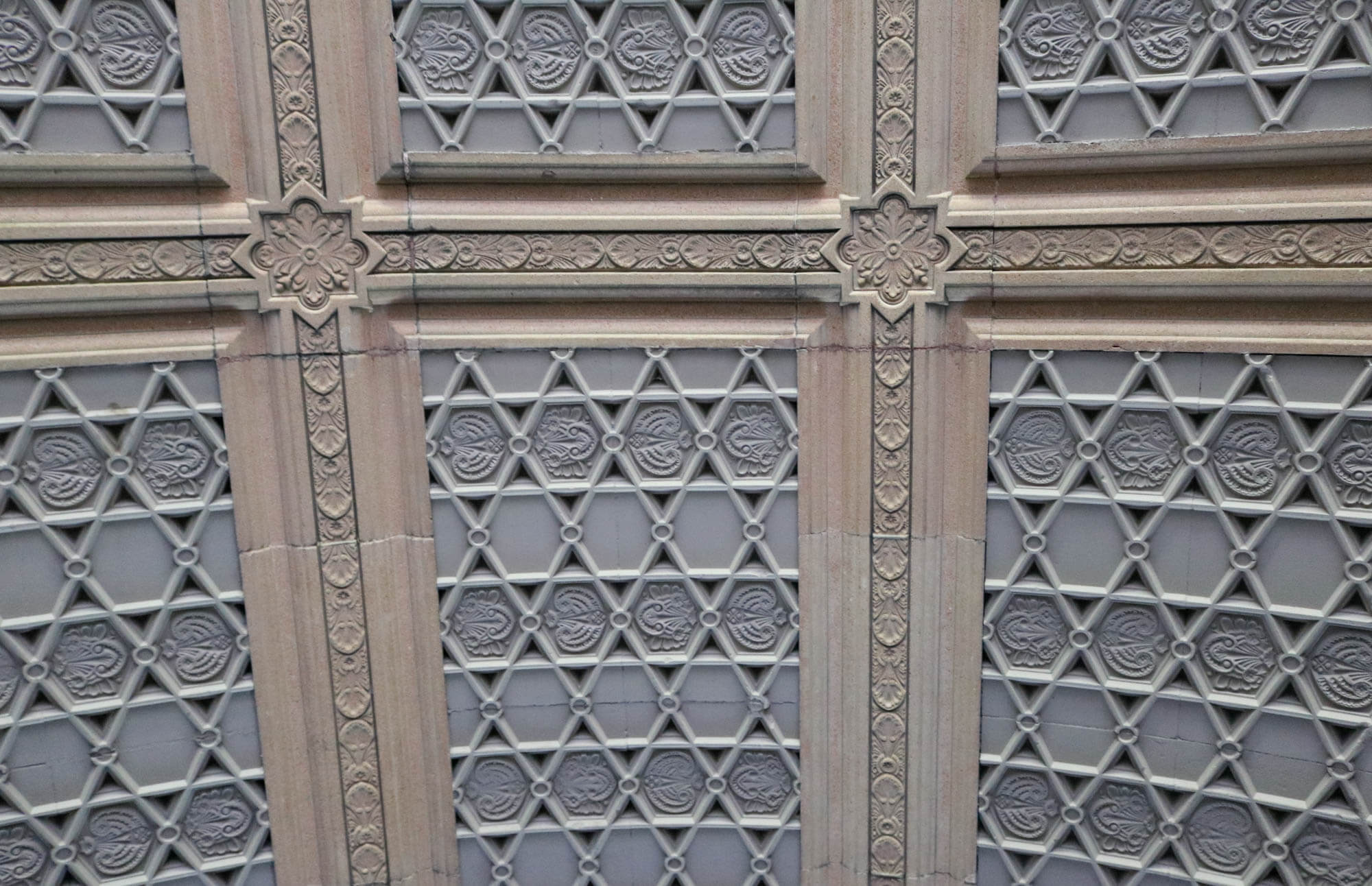

The cost-saving feature that appealed to the park commissioners was that a higher level of ornamentation could be produced in the new material with less time and labor than if rendered in traditional stone. Because the concrete could be cast in molds it meant that a repeating pattern — such as the span’s ceiling — would need a limited number of molds prepared to produce the finished design.

The commissioners also anticipated that the ability to color the pale gray of the Coignet stone before the hardening process would allow for a variety of colors in the finished design.

According to an 1878 article in the The Manufacturer and Builder, the span was completed at a cost of $20,000, versus an estimated cost of $250,000 if it had been built of stone. If accurate, the numbers would imply that the cost effectiveness should have satisfied the commissioners, but what about the design and durability?

Of the building process, Prospect Park’s engineer Joyn Y. Culyer wrote in an 1873 letter to John C. Goodridge that the bridge was built during the winter of 1871-1872 “under the most trying circumstances” and, after surviving two winters, he had “no doubt as to its continued durability.”

The experiments in color were apparently less satisfactory. On the exterior, the natural color of the Béton Coignet and a rougher finish were used. Across the ceiling of the span, smoothly finished panels were installed and bold shades of red, yellow and blue were attempted on the geometric and abstract floral patterns. Ultimately, the impact of the color was “much less decided than originally proposed,” according to an 1872 report by the landscape architects to the Brooklyn park commissioners.

However, they concluded, the experiment was “in the main satisfactory” and plans were made to use the material for a fountain basin at the entrance plaza to the park. (The fountain at Grand Army Plaza was replaced in the 1890s.)

While Olmsted and Vaux, along with a team of engineers, landscapers and builders, worked to create a bucolic landscape, they smartly used new technology to realize that vision. Whether it was creating the Wellhouse and an elaborate pumping system to keep water flowing in the man-made waterways or figuring out an engineering solution to move and plant large trees, technology helped them transform an expanse of forest and swamp into Brooklyn’s iconic park.

One can be forgiven for not noticing some of the technology in the park, designed as it was to be unobtrusive. Early sketches and photographs of the Cleft Ridge Span show it quickly embraced with foliage as if being overtaken by the natural world around it.

But, the easily missed structure should be added to a must-see list for a visit to the green oasis. The span is still considered a technical marvel. The superlative often assigned to it is that it was the first, and therefore oldest still standing, concrete arch built in the United States.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Prospect Park Transformed (Photos)

- Prospect Park’s Splendid Victorian Wellhouse Restored, Goes Green With Compostable Toilet

- How Many People Did it Take to Plant a Tree in Prospect Park in 1867?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment