Past and Present: The Henry Maxwell Memorial

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Of all of the places and buildings in Brooklyn that once were, and are now gone, I have to admit, nothing intrigues me more than the Mount Prospect Reservoir. It just amazes me that a large pool of water, which supplied most of Brooklyn with potable drinking water…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Of all of the places and buildings in Brooklyn that once were, and are now gone, I have to admit, nothing intrigues me more than the Mount Prospect Reservoir. It just amazes me that a large pool of water, which supplied most of Brooklyn with potable drinking water for almost a hundred years, was just sitting up on a hill behind and adjacent to the Brooklyn Museum. Of course, the Reservoir was there before the museum, but most of the photographs we have were taken when the museum was being constructed, or just after, just at the turn of the 20th century.

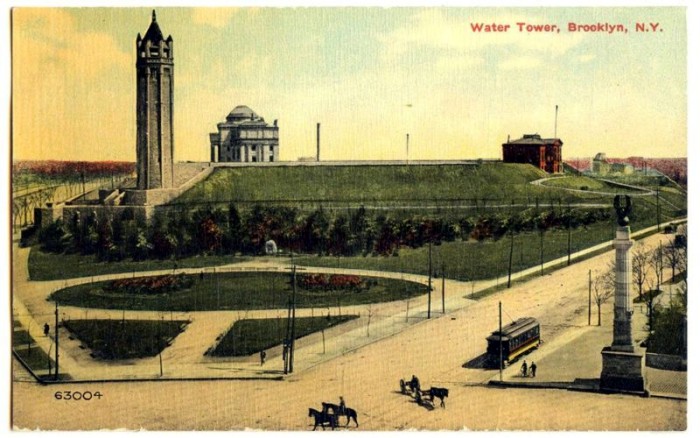

In addition to the lake, there were buildings connected to the waterworks, including a testing lab, a control building and a tall tower. All of those buildings were pretty cool, but I just love that tower. It’s simply elegant and very beautiful. I wish they could have somehow preserved it, or moved it somewhere else. I’ll be writing more about the tower and the reservoir at another time, because this post is not about the tower. The tower, in this case, served as a marker and a backdrop to a very special monument.

Brooklyn has always been filled with colorful characters who made it big and amassed great fortunes. Bankers have always been well represented in that group, and I’ve written often about these men, both the generous and the greedy. One of the good guys was a man named Henry Maxwell. His love of Brooklyn, where he was born, raised, and lived, was manifested in what he did with his considerable fortune. He made a lot of money, and he gave away a great deal of it to the people and the city he loved.

Henry Maxwell was born in Brooklyn in 1850. He grew up here and attended PS 15 as a boy. Later, he went into finance, and was a partner in the brokerage firm of Maxwell and Graves, with offices at 30 Broad Street. Maxwell was extremely successful and became a millionaire several times over. In addition to his brokerage, he was a director at several banks, vice president of a couple more banks, a trustee in even more, and sat on the boards of several large corporations. He also was in the insurance business, and was a director of the Long Island Railroad. He was also the President of the Long Island College Hospital and the Treasurer of the Polhemus Clinic in Brooklyn, which was part of the LICH.

Mr. Maxwell was also a strong advocate for education. He was a long time member of the Brooklyn School Board, and in 1898, when the city consolidated; he was one of six delegates from Brooklyn to the new Board of Education, where he served as the Director of Finance. He helped build Memorial Industrial School in Brooklyn, and dedicated it to his mother and wife. He received an honorary degree of Master of Arts for his educational work, bestowed on him by Columbia University. Henry Maxwell was also Brooklyn Parks Commissioner in 1884. A busy man, indeed.

Maxwell made a lot of money and gave quite a bit of it away, most of it without a lot of publicity or public knowledge. Much of his charity was health care related. He funded the Maxwell House, a clinic on Concord Street, on the Dumbo/Downtown border, once filled with tenements and the working poor. He gave LICH $60,000 to pay for the operating room in the hospital, and the same amount to build a nurse’s dormitory across the street from the Polhemus Clinic. He also donated $20,000 to the victims of the Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania, in 1889.

A lot of his charity was in the little things. Maxwell and his family lived at 72 First Place in Carroll Gardens. He knew every doctor, druggist and pharmacy in South Brooklyn. They all were under his instructions to treat anyone too poor to pay for care or drugs, no matter what the cost. The caregivers were told to just send him the bills, and he’d pay them. Maxwell didn’t want the recipients to know who was paying for their care. In addition, he also paid to send poor and sickly children from the tenements to the seashore and the mountains for the summer, as participants in programs run by various charities. They did not know the name of their benefactor either.

It was estimated that during his lifetime, he donated over $300,000 a year to charity. Someone that generous and giving is often too good for this world, and Henry Maxwell did not live a long life into old age. He died of a stroke at the age of 52 in 1902. The flags of all of Brooklyn’s schools were lowered to half-mast on the day of his funeral, out of respect. Soon afterwards, his friends and colleagues wanted to memorialize this good man with a public monument. They commissioned one of the most prominent sculptors of the day, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, to design a memorial plaque for Henry Maxwell.

Saint-Gaudens created a high-relief depiction of Maxwell framed by ribbon-like garlands. The bronze plaque was affixed to a huge boulder of pink granite weighing over 20 tons. The monument was placed prominently in the center of the intersection of Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Avenue, and was draped with an American flag for its dedication on December 26, 1903. The monument can be seen in the center of the postcard showing that part of Grand Army Plaza, below.

In 1912, plans were being made to construct a new Brooklyn library in that location, and the monument was moved to its present location, the little hillside berm nearby, at Plaza Street and St. Johns Place. It reportedly took a crew of men and ten horses a week to move the 20 ton rock across the street. The original library designed by Raymond Almirall was never completed, stalling by late teens, and it wouldn’t be until 1938 that construction was resumed, with new architects and a new design.

By that time, the reservoir was also doomed. Brooklyn was now getting its water from the same upstate reservoirs that supplied Manhattan and the rest of the city. The Mt. Prospect Reservoir was now obsolete, and was drained in 1940, and the land turned into a city park called Mount Prospect Park. The water tower and the other buildings connected to the reservoir were also destroyed. Today, the Brooklyn Central Library stands where the monument of Henry Maxwell once stood. From the photographs, it looks to be right about where the front door is.

Over the years, the Maxwell memorial was covered up by overgrown foliage, and the bronze plaque and the stone were tagged by vandals. The Parks Department decided to remove the original Saint-Gaudens plaque in the 1970s, and it sat in storage for another 20 years. In 1997, with the financial help of the David Schwartz Foundation, the plaque was cleaned, repaired and restored. Two copies were made. One was a replacement for the memorial stone; the other went to the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, in Cornish, New Hampshire. The original is now in the Brooklyn Museum. Today, effort is made to make sure the grounds around the memorial are kept trimmed, so that the plaque and stone are easily visible.

It’s a shame that the great people of our past are so quickly forgotten. No one knows today who Henry Maxwell was. I had never run across his name until doing research for this article. But only a little more than 100 years ago, he was a force for good in this city, quietly making the lives of the poor and disadvantaged better, without fanfare or accolades during his lifetime. Thousands of children and their parents, who were kept alive, or educated by him, may have made their way from poverty to a better life, because he gave them a chance. Perhaps that’s more than enough reward right there. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment