The Restful Beauty of the Cemetery of the Evergreens

The Cemetery of the Evergreens is one of our borough’s great park cemeteries, a place where people went to not only visit their departed loved ones, but enjoy the beauty of nature, take in the views and vistas, and relax in a restful glen or bower.

Photo by Susan De Vries

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2012. Read the original here.

Like the much larger and more famous Green-Wood Cemetery, The Cemetery of the Evergreens, as it is officially called, is one of our borough’s great park cemeteries; a place where people went to not only visit their departed loved ones, but enjoy the beauty of nature, take in the views and vistas, and relax in a restful glen or bower. For space-starved Victorians of all incomes, this free park was a restful place to experience nature and art, and it was a popular tourist attraction, just like Green-Wood.

The great park cemeteries of America had their birth at Mount Auburn Cemetery, near Boston, established in 1831. Before that time, cemeteries were most often in churchyards or on private land. Taking their cue from English landscape design, the American rural or park cemeteries were designed to be a carefully planned “domesticated landscape,” where natural features like hills, trees and lakes were augmented by winding roads and paths, and the planting of trees, flowers and shrubs. And, of course, tombstones, mausoleums and monuments.

The park cemetery was a popular success, fueled in part by the Romantic era in literature, music and art. Prose and poetry painted pictures of castle ruins on a rocky hill, and mourning maidens draped in wind-swept shawls and trailing gowns wept over their lost loves. This would not be the first time that popular culture has affected our physical environment, and you can see that imagery and imagination in some of the monuments.

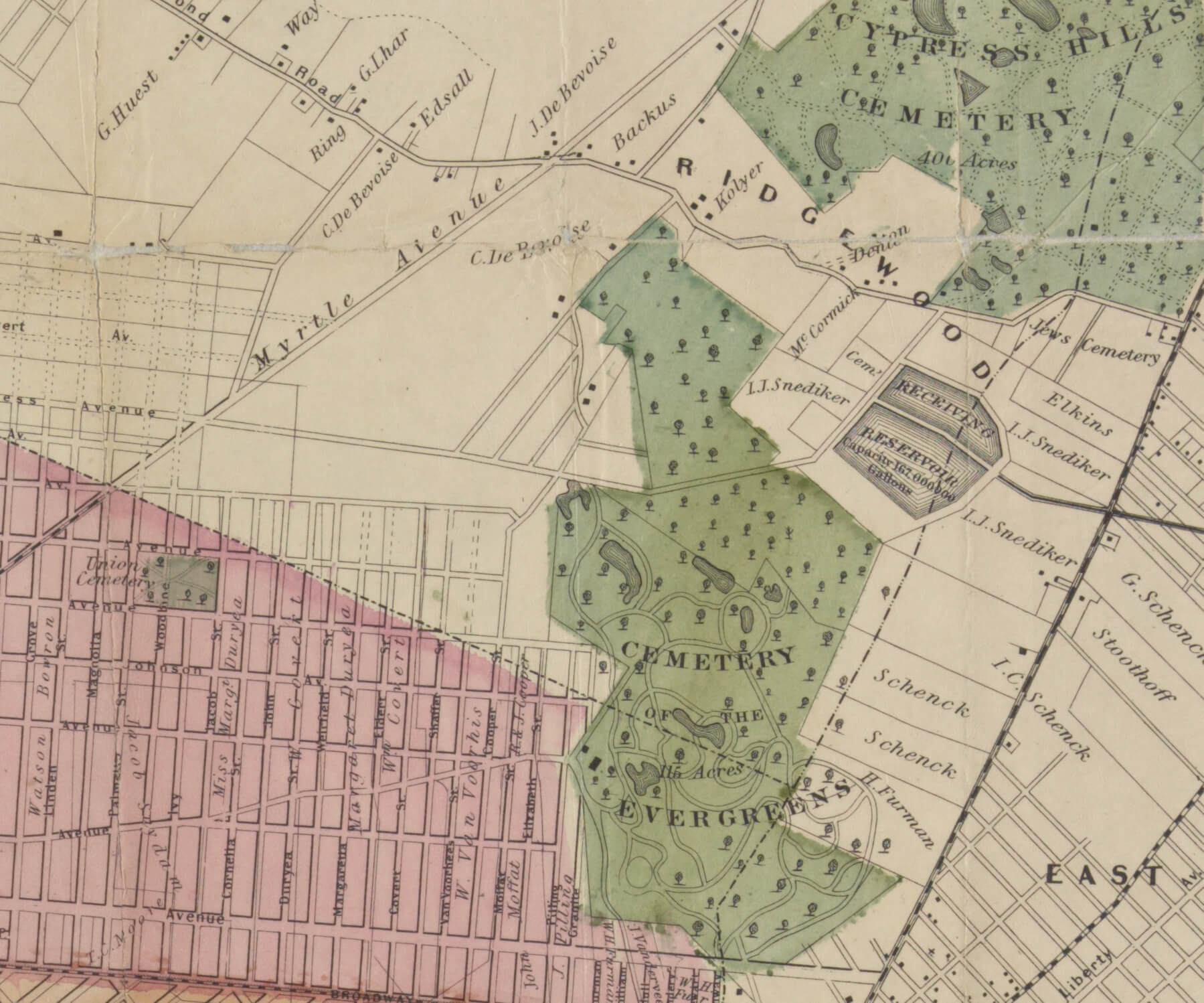

Five years after Mount Auburn opened, there were at least six other park cemeteries being developed across the country, including Green-Wood Cemetery here in Brooklyn, which opened in 1838. More soon followed. The Cemetery of the Evergreens was established here, on the Brooklyn-Queens border, in 1849, and nearby Cypress Hills Cemetery, which is actually more in Queens but often confused with Evergreens, opened a year earlier, in 1848. Both were established as nonsectarian cemeteries, which meant they accepted people of all faiths and persuasions.

Two years before Evergreens opened, the New York State Legislature had passed the Rural Cemetery Act, which was designed to authorize commercial burials in the state. That meant that people would no longer be buried in churchyards or in the backyard garden, but would have to be buried in tax-free land set aside for cemeteries, outside of cities.

The law was basically passed because Manhattan was running out of room to bury people, and public health advocates were also making the link between disease, water tables and graveyards. Manhattan had passed a law in 1852 prohibiting any more Manhattan burials. (This didn’t include far uptown.) Brooklyn had already passed a similar law in 1849. At the time, Brooklyn consisted of only the old town of Brooklyn, and this area was its outermost reaches, bordering New Lots. New Lots was itself a part of Flatbush, which was a separate and independent town.

Before you knew it, the outskirts of Brooklyn and Queens became the cemetery capitals of New York. To this day, Queens wins the race, having 29 cemeteries with over five million inhabitants, making more people in Queens under the ground than above it. Brooklyn and Queens have 17 cemeteries, including Evergreens, that straddle both boroughs. As Manhattan grew, more and more old cemeteries and churchyards dug up their dead and reinterred them in this area, especially in Cypress Hills Cemetery, although Manhattan’s dead also ended up in Green-Wood and Evergreen, as well as Woodlawn in the Bronx. When the Brooklyn Bridge was being built, beginning in 1870, the dead who were buried in the Sands Street Methodist Churchyard were taken to Evergreens, and laid to rest once again.

With all of the dead coming to rest in these new cemeteries, great planning was needed to make them efficient and beautiful. Two of the greatest landscape architects of the day had their hand in designing the Cemetery of the Evergreens: Andrew Jackson Downing and Alexander Jackson Davis. Downing is known as the “Father of American Landscape Architecture,” and was a prolific landscape designer, horticulturist and writer. Originally from Newburgh, N.Y., he wrote extensively on landscaping and horticulture, and was a prominent advocate for the Gothic Revival style.

It is easy to get him confused with Alexander Jackson Davis, as the names are so similar, but Downing was mainly a horticulturist, although he did dabble in architecture. It was he who persuaded Calvert Vaux to emigrate from England, and we also have Downing to thank for the popularity of the front porch, an idea he strongly approved of as a bridge between the indoors and nature. Since his writings and projects were so popular during his lifetime, he got an opportunity to be an advocate for many ideas. The most important may be his philosophy that architecture should fit into nature and be an organic part of the whole, a very modern concept for his day.

Alexander Jackson Davis was the architect. He was also a New Yorker, and one of the most important mid-19th century architects in America. He was a champion of the villa, those suburban mansions that he designed for his wealthy clients in the Hudson Valley and elsewhere. He is best known for Lyndhurst, a Gothic Revival masterpiece that would later become the home of financier Jay Gould, and was the architect of the first Italianate-style Tuscan villas in America. And of course, he designed the Litchfield Mansion, now part of Prospect Park.

He teamed up with Downing to illustrate some of Downing’s books on landscaping and architecture, and they worked together on the designs of the Cemetery of the Evergreens, as well as other projects. Downing was an artist. His canvas was the landscape, and his brushes were trees, shrubs and flowering plants. A look around Evergreens shows the hand of a master. His winding roads encircle old-growth trees as well as new. Anyone who knows their trees knows that most of the species would never have come here naturally, but Downing had them planted where they would look the best.

As the eye wanders, you have the textures, shapes and colors of the different species; straight, gnarled, branching, tall and slender, bright green leaves, fir trees, with purples, reds, hunter green; with large leaves and small; every variety possible for this climate, arranged with beauty in mind. Flowering shrubs and planted beds complement the trees, and in the grassy fields, and under spreading branches, the dead rest in beauty. And off in the distance, the skyscrapers of Manhattan and Jamaica Bay both can be seen.

Today we regard death much differently than the early Victorians who built these cemeteries. Life was hard for most people, life expectancies were much shorter in general, and for rich and poor alike, death could easily come from childbirth, disease, accident or war. Unlike today, when modern medicine and better living conditions have pushed death as far away as possible, the Victorians embraced it as a part of life. Funerals generally took place in the home, and burial in a beautiful park where one could visit, and even make a day of it, proved extremely popular.

Green-Wood and Evergreens have much in common. Both are built on the same terminal moraine, high ground left by the progress of the glaciers millennia ago. Both sites also played a much later role in the Revolutionary War. The first great battle of that war was fought in Brooklyn in 1776, when the British and their Hessian allies landed at Gravesend Bay and pushed forward to Flatbush, intending to defeat George Washington’s newly formed American army, and put a quick end to the American rebellion.

As the British troops progressed through Brooklyn, the army of over 10,000 men stretched for miles. When they reached New Lots, they forced William Howard and his son, local tavern keepers, to lead them on the old Rockaway Footpath, an Indian trail that today runs directly through the Cemetery of the Evergreens. The British marched to the town of Bedford and then on to Gowanus, where the bloody battle between the forces took place. This includes the high ground, now part of Green-Wood Cemetery. Both cemetery sites are important memorials to the first major battle in the war of American independence.

One can certainly see why this Rockaway trail would be important to both the native people who created it and later colonists. The view from the top of the cemetery is impressive. Situated almost in the center of Brooklyn, one can see the towers of Manhattan rising on one side and the lowlands of East New York going towards Gravesend Bay in the other, both much farther away than they look. What a change in only 200 years, from wilderness and small towns to an entire view now of a city of millions of people and thousands of buildings.

When Downing and Davis laid out the Cemetery of the Evergreens, they did so with the intention of maximizing the park-like features of the natural rolling hills and that great view. The entrance to the cemetery on Bushwick Avenue leads a visitor up the hill on a winding road that leads to the chapel at the highest point on the hill. It’s a beautiful Gothic Revival country church, which was designed by Davis and later modified by Calvert Vaux. Across the street is a circa 1880s rustic shelter called the Summer House. It was designed to be a gathering place for mourners.

And who were those who came to mourn? Evergreens is non-sectarian, not dedicated to any one denomination, faith or following. A look at the older and more impressive monuments shows that the cemetery was very much used by a wealthy German-American population in the latter part of the 19th century. Most of the names on the rows of mausoleums are German, as are many of the largest monuments, some with German inscriptions. There are brewmeisters, industrialists and ministers, as well as ordinary folk. Interestingly enough, many seemed to order the same monument, a tall obelisk on a pedestal with Neo-Grec patterns. It shows up a lot in the German part of the cemetery. It would be interesting to see if there’s a story there.

There is now a very large Chinese section of the cemetery, dating from the last half of the 20th century into the present. And of course, there are the famous and infamous buried here. Some of Evergreen’s more notable residents include cartoonist Walt Kelly, jazz saxophonist Lester Young, Amy Vanderbilt (the manners columnist), entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and actor William Hickey, as well as several early major league baseball players, several chess champions, late 19th- and early 20th-century actors and entertainers, and artists.

Two more recent residents, who made the news in the last 20 years, are murder victim Yusef Hawkins, who was killed while walking through Bensonhurst, and City Councilman James E. Davis, who was murdered in the City Council chambers. He was originally interred in Green-Wood Cemetery, but when it was discovered that his murderer was also buried there, his body was brought to Evergreens. His monument is right on the main road to the chapel.

The cemetery also is the final resting place for some of the people in the worst tragedies in New York City’s history. Eight of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory disaster are buried here, interred under a large monument. It was only recently that researchers were able to identify the bodies and give names to six of the victims.

Also buried here are victims of the Brooklyn Theater fire of 1876, in which over 200 people lost their lives. Over two dozen of the named victims are here in various parts of the cemetery. The Walkabout story of this horrific fire can be found here and here. In 1904, a large group of German-American churchgoers from the Lower East Side crowded on the General Slocum ferry in Manhattan to enjoy an outing to Long Island. The boat caught fire in the harbor, and the resulting conflagration would kill over 1,000 people, most of whom were drowned, trampled or burned to death. The dead were buried all over New York City, with more than 50 interred in Evergreens, all identified and individually buried by their families.

The Cemetery of the Evergreens has a large section of plots reserved by the New York Actors Guild. Bill Robinson and others are buried there. Actors and entertainers were not always as highly admired as they are today; in fact, in the Middle Ages in Europe, they could not be buried in sacred ground. It was important for the Guild to be able to have plots available, especially for those in the profession who were not household names, ensuring that these people could rest in peace with their peers in a place where they were welcomed.

Also welcomed were sailors who died in New York City. The grassy knoll at the front near the Bushwick entrance has markers showing the countries where these sailors originally hailed from. There are markers noting lands all over the world. There are Civil War veterans, all but one from the Union side, buried across the cemetery. This includes two Medal of Honor recipients. Included among the Civil War dead are members of New York’s 20th Regiment, an all-Black regiment, one of the segregated units of United States Colored Troops that marched into war in 1864. Many are buried in the plot belonging to the Frederick Douglass G.A.R. Post, the veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic.

The Cemetery of the Evergreens is not as crowded as Green-Wood. Most of the sections, even in the oldest parts, do not have the headstones packed next to each other as tightly as in some parts of Green-Wood. Personally, I like old cemeteries. As they were designed to be, I find them beautiful, peaceful and artistic. The artistry of the stone carvers can be just amazing, with some real works of art in place. Many of the mausoleums have beautiful stained glass panels visible through the gates, and many of those gates are impressive examples of metalwork and sculpture. The landscaping is beautiful, and while Green-Wood is certainly more impressive, with lakes and more hills, Evergreens allows you to see the manmade play of horticulture and environment with a bit more perspective, keeping with the idea of a park. I highly recommend a trip, to see for yourself.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- The Gothic Inspired Chapel of Green-Wood Cemetery and Its Well Connected Designers

- Monumental Conservation: Green-Wood Cemetery Gains a Conservator

- Saving the Tiny Cemetery of Bay Ridge

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment