George and Susan Elkins, Their House, and the Really Big Meadow

Restored after years of neglect, Crown Heights’ oldest house recalls a time when farms and country villas dotted the area.

Photo by Susan De Vries

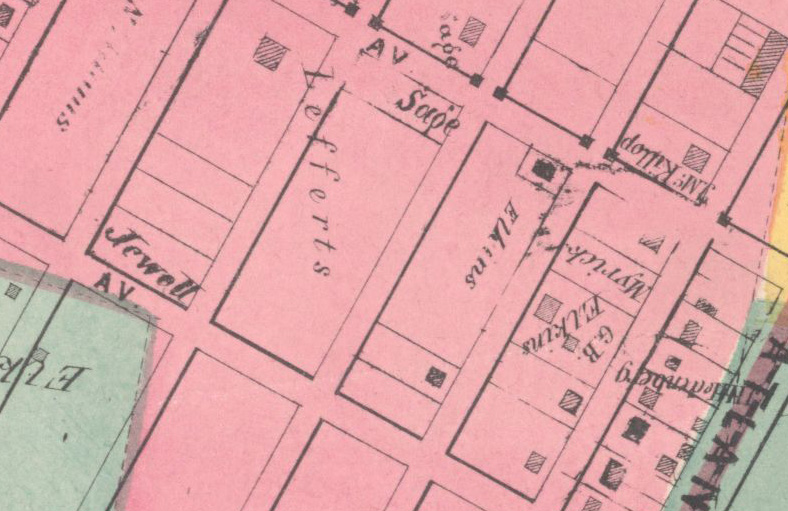

Imagine Central Brooklyn as it looked in the decades before the Civil War. The neighborhoods we call Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights North were part of the town of Bedford. Most of it belonged to various members of the Lefferts family, whose family seat at today’s Fulton Street and Arlington Place was smack in the middle of the crossroads making up the village of Bedford Corners.

Brooklyn, which included Bedford, was incorporated as a city in 1834, and the street grid was laid out by 1839. The grid was aspirational, extending far past what was already a growing city, through hill and dale, farms, and woodlands that wouldn’t be urbanized until 50 or more years later.

Landowners knew that sooner or later their grazing and crop land would be much more valuable as buildable lots than it was for farming. The Lefferts family, in particular, had a LOT of land. So little by little, and sometimes acres upon acres, they began selling off parcels to aspiring developers and land speculators. Some of this land consisted of small farms with tenant farmers; other land was simply left alone and used for grazing. Much of it was hilly and entire tracts were wooded, the trees used for fuel and lumber by more than just family members.

Well before his death in 1847, patriarch “Judge” Lefferts Lefferts Jr. began chipping away at his holdings. Since his family’s land stretched from today’s neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant all the way east to East New York, he wasn’t going to miss losing any acreage. Included in those sales was the land that in 1838 became the African American town of Weeksville.

After the judge’s estate was finally settled in 1854, his heirs cashed in big time, selling off his Bedford farm, advertising it as “1,600 desirable lots situated in the level, beautiful, and most desirable part of the 9th Ward.” Public transportation was developing throughout Brooklyn, and the section benefited from its proximity to the Long Island Railroad (which began operations to Jamaica, Queens, and beyond in 1834) as well as established stagecoach and, later, trolley lines along Fulton Street and Atlantic and Bedford Avenues.

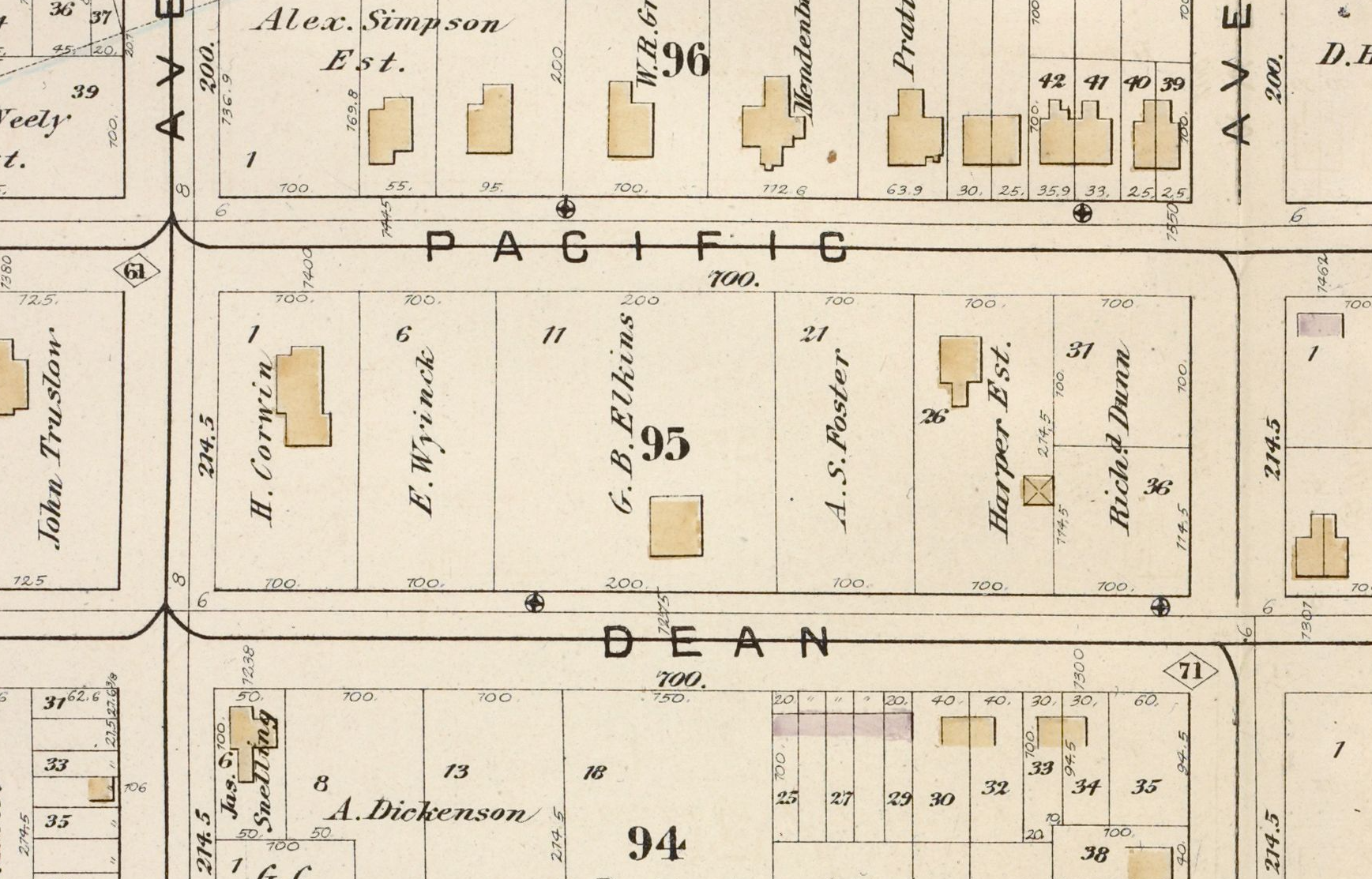

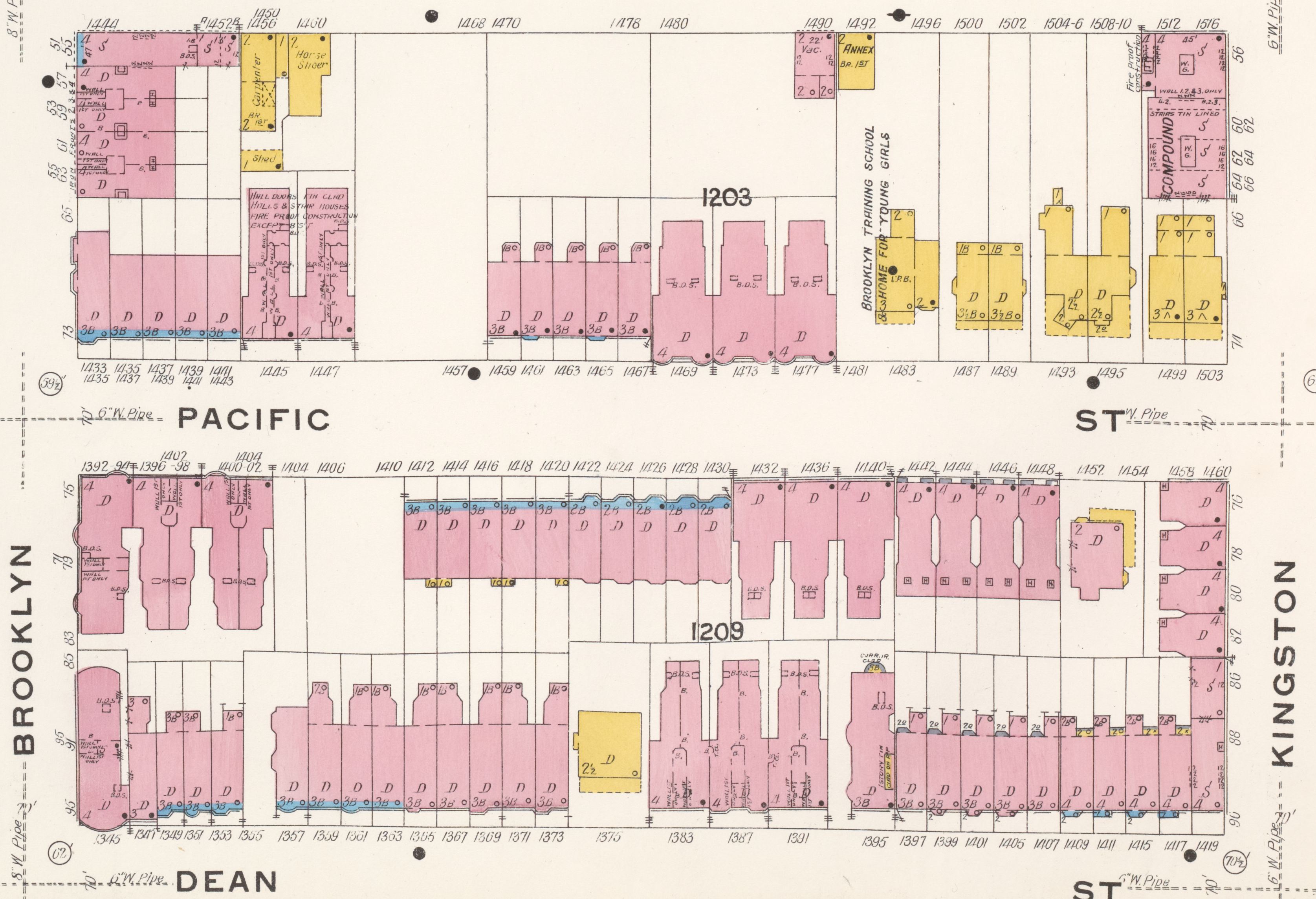

Various land speculators were interested in these lots. A Manhattan merchant named George W. Folsom saw the possibilities of the development of suburban retreats for wealthy Manhattan merchants and businessmen. He purchased two entire blocks, which were bordered by Brooklyn Avenue, Hudson Avenue (now Kingston Avenue), Pacific Street, and Bergen, with Dean Street running through the middle. Of course, none of these streets existed anywhere except on maps at this point; his land was a very large open field or meadow with hillocks and berms and a view of the woods south of it.

Somewhere around 1855 or 1856, he built a villa on a small hill in the center of his property, facing a newly created Dean Street. It was surrounded by generous grounds, with enough space to raise a few farm animals and build a barn and stable on the Pacific Street side. In 1857, he listed his address in the Brooklyn Directory as “Dean near Brooklyn Avenue.” There were no house numbers at that point.

Folsom and his family didn’t get to enjoy the property for very long: He died two years later, in 1858, and his widow, Elizabeth, put the house and surrounding land up for sale. The ad for the house published in the Brooklyn Eagle in April of 1858 read:

“For sale – a large and commodious Dwelling House, the late residence of Geo. W. Folsom, deceased, on Dean Street, between Brooklyn and Hudson ave., 9th Ward, Brooklyn, together with 16 lots of land, carriage house, etc. Also, a number of vacant lots, eligibly situated. The Fulton Avenue cars run very near the premises. Terms easy. Enquire on the premises of Mrs. Folsom, or of Hagner & Smith, 9 Court st. Brooklyn.”

The property was snapped up by John and Mary McKillop in 1859. He was a merchant familiar with Folsom, and the property was purchased in Mary’s name. Historians speculate that they saw the opportunity to buy the land and flip it for a nice profit. Into the picture steps George B. Elkins and family.

George was born in Massachusetts in either 1808 or 1809. While still in that state, he married Susan Easton in 1839, and they had their daughters, Mary, Georgianna, and Fanny in subsequent years. The family moved to Brooklyn and lived on Willow Street in Brooklyn Heights by 1845, when youngest daughter Ida was born. At the time, George was listed as a merchant, with his business headquarters in lower Manhattan. Ads in the local papers show that among the goods he sold were imported hides and wool. He owned a couple of barks, small sailing vessels that he used to transport his goods.

The Elkins family purchased the estate from McKillop, who only owned the parcel for a fast five days. Records show the property was purchased by Susan Elkins. The family moved to the 9th Ward and were living at Pacific near Kingston Street by 1861, and by 1865 were listed as living on “Dean near Brooklyn.” It remains unclear if the family moved into the house built by George Folsom, or if a new home was constructed for them after they purchased the property.

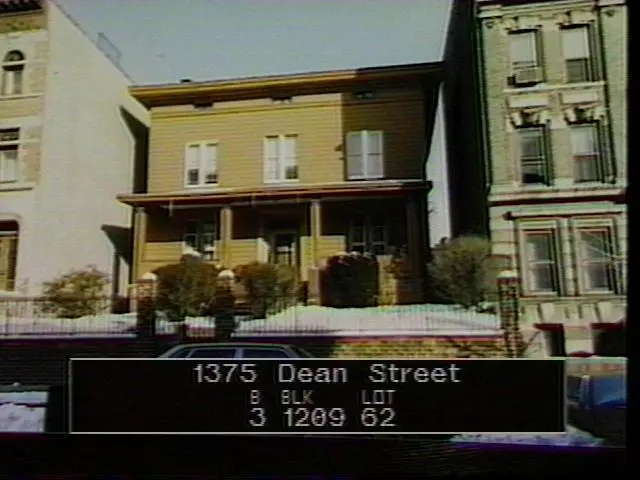

By 1870, the address for the property was listed as 1275 Dean Street. It remained 1275 Dean until the 1890s, when the street was renumbered and it became 1375 Dean Street, the current address. Whether it was built in 1855 or a bit later, it is still the oldest standing house in Crown Heights North.

The house is a large two-and-a-half story Greek Revival/Italianate wood-frame building with a large porch supported by four columns. The style of the house was in keeping with the villa designs that were very popular at the time, especially those of Andrew Jackson Downing. The front facade is three bays wide, with a center doorway, a flat roof, and delicate details in the attic window frames. It still sits on a rise, well above the lower street grade established in the 1870s.

George’s new home was the catalyst for him to branch into a new line of work. By 1861, the Brooklyn City Directory lists him as being in real estate. He opened an office on the corner of Fulton and Clermont Street in Fort Greene and began selling, mostly in his new neighborhood. For the next few years his ads ran in the Brooklyn Eagle. Bedford was slowly developing during the Civil War years, and he sold both houses and undeveloped lots.

One ad posted in the Eagle in 1864 reads, “For Sale—very desirable residences at Bedford—on New York Avenue and Pacific Street, with four, eight, 16, or 24 lots, with stable and all modern improvements, fine forest, ornamental, shade and fruit trees, shrubs and vines, greenhouse, flower and kitchen garden, well stocked with choice flowers, fruits, vegetables, etc., etc., near two lines of cars, running to all the ferries every five minutes. Also, very desirable villa sites on Atlantic, New York, Brooklyn, Hudson, and Albany Avenues and Pacific, Dean, Bergen, Warren and Baltic streets and St. Mark’s Place, in parcels of four to 24 lots…. Now is the time while lots are low and houses are selling at almost fabulous prices. Apply to G.B. Elkins, 338 Fulton Street, Brooklyn.”

Potential buyers wanted to see what they were buying, of course, and since George and Susan’s house was right in the middle of it all, it’s easy to imagine George bringing his clients to his house, a feature he offered in his ads. Standing on his high porch, looking down in all directions, his clients could see for miles as George painted a picture of stately villas on ample land like his, their object of privacy, space, and elegance laid before them. If that was too expensive, he also offered lesser priced properties and houses.

Buying and holding properties, often in Susan’s name, George became a speculator as well as a realtor. Brooklyn city records show that in the 1860s and ‘70s, more than 190 transactions took place under their names, all between Atlantic Avenue and Butler Street (now Sterling Place) and from Albany to Brooklyn avenues.

One would think that with that kind of record, there would be a street named after them. After all, there are roads named for developers such as Charles Hoyt and Russell Nevins. While George may have been a great salesman, he was not a great property owner. He and Susan spent a lot of time in court, and seemed to have lost as much property to foreclosure as they were able to successfully sell.

The Victorians in the years during and after the Civil War thought it unseemly and ungentlemanly to drag a woman into court for foreclosure and other financial cases. That was one reason many men registered their property and businesses with their wives or other female relatives. It also shielded the men from the courts seizing property for their mistakes or debt. But as the decades progressed and more and more women were listed as owners, the courts got over their squeamishness and treated women more equally, at least in terms of foreclosure and other civil liability.

Frequent foreclosures for both continued over the years. Research turned up hundreds of mentions of Elkins in the local papers, but 80 percent pertained to foreclosure sales of various properties they owned. Even after both George and Susan were dead, their daughters were still being foreclosed on for their parents’ (mostly his) debt. What happened?

By 1870 George had expanded his business to include contracting. He won a bid to build and pave parts of Eastern Parkway. Four years later, he won another contract for the extension and pavement of a 5,000-foot stretch of Brooklyn Avenue. Both were within his general sales area.

Between his property acquisitions, his developed properties, his real estate sales, and his contracting business, George was now a wealthy man. Not a millionaire, but on his way, and referred to as a “gentleman pretty well known in this city.” He began dabbling in local Republican politics, an activity many wealthy men took to eagerly. He had some minor appointments in his district and hosted political soirees in his home. His new political connections led to a partnership with lawyer William M. Evarts.

Andrew Johnson became president after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. Evarts was President Andrew Johnson’s third attorney general and his attorney during his impeachment trial in 1868. He later became President Rutherford B. Hayes’s secretary of state — and much later became a New York State senator.

Elkins and Evart joined forces in 1872 to buy plots of land in what is today Crown Heights South. Their holdings were near the Kings County Penitentiary, the large and forbidding county prison located between the towns of Bedford and Flatbush. The institution took up a square of land between Nostrand and Rogers and President and Crown streets.

They bought their plots from Kings County for around $20,000, a large sum at the time. They probably thought it would be prime land for the development of housing, but they miscalculated the negative connotations of being near the prison as well as one of the periodic financial downturns called the Panic of 1873. It was a costly mistake.

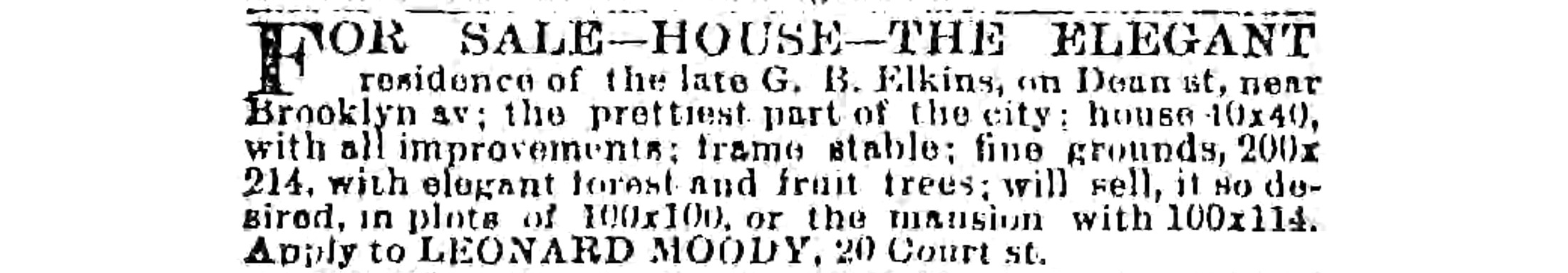

George and Susan’s foreclosures were coming fast and furious in the 1870s. Susan died in 1883, and George’s financial state was so bad that he lost title to 1275 Dean Street in yet another foreclosure. Fortunately, his daughter Mary was able to pay the debt and became the owner of the property.

But the property near the prison continued to plague him. He paid $20,000 for it, but with the interest accruing over the decade, by 1884, he still owed the same amount, couldn’t pay it, and a foreclosure was issued. Thanks no doubt to the influence of his partner William Everts who was about to be in Congress, and a friendly court supervisor who advocated for him, the courts and the city had mercy on him, and just took the land back without further penalties.

By this time, George was an old man, a widower, and pretty much penniless. Fortunately for him, his three daughters had their own occupations and a decent amount of land surrounding the house, and George still had a roof over his head at 1275 Dean. He died on March 15, 1886, at home at the age of 77. The cause of death was listed as heart disease. The newspapers said he “died poor.” His funeral was held at 8 p.m. in the house two days later. George left his daughters, especially Mary, as the eldest and legal heir, with a sizable portion of debt. More property would be forfeited to wipe clean his slate.

The sisters were resourceful and talented. Fanny and Ida were artists. Fanny was making a living producing anatomical and other drawings and lecture preparation materials, and Ida was listed as an artist in an 1882 guidebook for “artists, art students, and travelers.” The two sisters were also inventors and had several patents under their names for creations such as a type of desk fan and an automatic fly swatter. All four sisters remained single, and all lived in the house most of their lives.

By the 1890s, they began selling the land surrounding their home. They stipulated that the land could contain only private dwellings or first-class flats. Their first sale was to the developer John Bliss, who purchased lots facing Pacific Street. He flipped the lots to George Phillips, upon which were built five first-class row houses designed by noted architect George P. Chappell, all of which are still standing. (There are a lot of Georges in this story!)

In 1897, more Pacific-facing lots were sold, and more townhouses built — this time, in 1898, elegant Renaissance Revival two-family homes. The lots immediately east and west of the family house were sold and developed, sandwiching 1375 Dean Street tightly in between them. George P. Chappell designed five single-family townhouses just west of the house for Arthur Stone in 1892. In 1905, Axel Hedman designed three flats buildings on the site east of the house, for developer Edward J. Maguire. The Elkins house was now the only pre-Civil War house in the neighborhood.

The early 20th century saw Fanny Elkins teaching at Public School 116 in Bushwick. Ida died in 1904, leaving the remaining three sisters, who appear in the 1910 census. Georgianna died in 1915, and a year later, the eldest sister Mary passed away. Fanny was now the last of the Elkins, rattling around in a big empty house. Between the memories, expenses, and effort of holding onto the house, Fanny, who was now 73, decided to sell. In 1918, the house was bought by Joseph Cohn, the first non-family member to own the property since 1860. The Elkins family lived there for almost 60 years. Fanny moved to Queens, where she died in 1923 at the age of 81. She and her entire family now rest in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Joseph Cohn and the owners who followed have their own unique stories to tell, some of them quite fascinating, and deserving of their own piece. The story of this house and its owners throughout the 20th century is a microcosm of the history of the neighborhood. But by 2006, the house was boarded up and scheduled to be demolished. It was saved only by an emergency individual landmarking that stopped the demo as the bulldozers and backhoe were headed for the site.

The owner disgustedly put the house up for sale, rejected real offers, and then walked away. Several owners and subsequent deterioration of the house continued a downward spiral. Deliberate property damage and looting followed, accompanied by absurdly high asking prices. In 2014 the house was finally purchased by a developer who cared about it and worked diligently with the Landmarks Preservation Commission to restore it and put it back on the tax rolls. Today it is one of the highlights of the block and of the Crown Heights North Historic District, established in 2007.

The dwelling at 1275 Dean Street has a 170-year history as the property of a host of families and individuals. This is the most storied house in Crown Heights North, saved and safe at last. The George and Susan Elkins house will always be remembered for the early family who made their home there.

Standing on his porch, George saw a vista of farmland, woods, and hills stretching for miles around him. He saw his own property taking up two square blocks of valuable land. He brought his clients there and showed them the possibilities. Money was made on that porch and with that view. The Brooklyn he worked so hard to sell and develop is even more valuable today than ever. George would be pleased.

Related Stories

- After Long Struggle, Crown Heights Antebellum Jewel Susan B. Elkins House Restored at Last

- New Owner of Crown Heights’ Oldest House Plans Condos

- Oldest House in Crown Heights North Now More Ruined and Expensive Than Ever

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment