Here's What You Should Know About 421-a and Its Incredible Impact on Development in NYC (Updated)

Editor’s note: A new deal was struck in November of 2016. Click here for all the details. Hated by many, beloved by some and misunderstood by most, the 421-a tax abatement expired on Friday after the Real Estate Board of New York and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York failed to come…

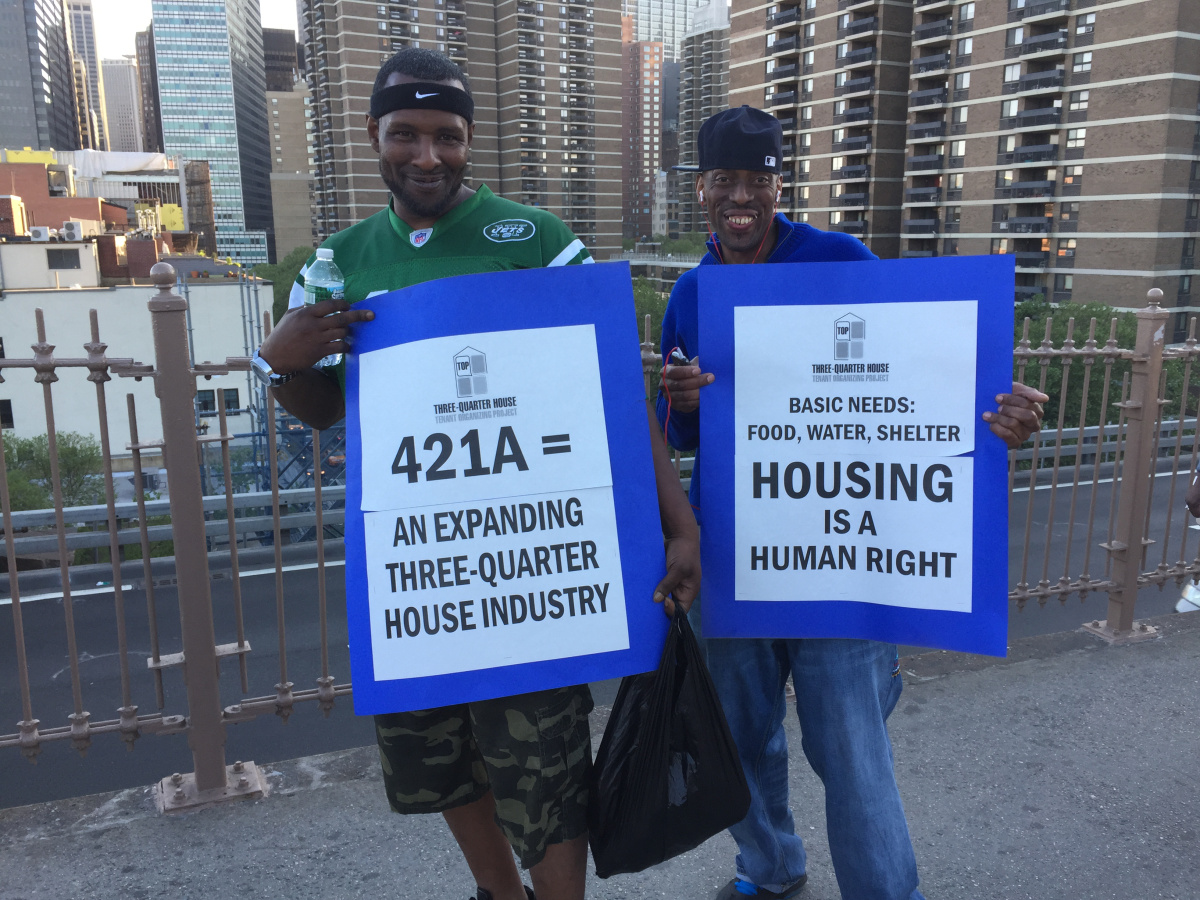

Construction workers at a rally demanding prevailing wages in a 421-a renewal. Photo via The We Party

Editor’s note: A new deal was struck in November of 2016. Click here for all the details.

Hated by many, beloved by some and misunderstood by most, the 421-a tax abatement expired on Friday after the Real Estate Board of New York and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York failed to come to an agreement regarding its extension.

But what was the 421-a tax break? And why should you care?

The 421-a tax break has a huge influence on construction and affordable housing.

It’s basically a 10-year tax exemption for certain developments that include affordable housing. This can save developers millions of dollars a year and convince them to make affordable units.

“We think stopping 421-a will halt supply like crazy,” said developer David Schwartz of Slate Property Group at a recent gathering of real estate pros.

421-a saved development in NYC.

The program was created in the early 1970s — a time when the city was not a desirable location — to get more developers building.

Albany renewed the profoundly effective abatement in 1977 after data found that 421-a was responsible for 90 percent of the city’s new residential construction.

By 1985, the city was doing great on development. But after a certain Donald Trump was awarded a $50 million tax exemption for the Trump Tower using 421-a, the city decided to rethink its strategy.

The 421-a abatement was rewritten so that only developments within a certain area — now all of Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx — would qualify, and only if they had a certain number of units of affordable housing, according to a timeline by the Municipal Art Society.

Over the past 30-odd years, it has created more than 10,000 units of affordable housing, according to the NYU Furman Center.

But recent investigations have found that developers don’t always play nice — with some taking the tax break but keeping their units market rate.

Who hates 421-a? Tenants and tax payers.

Like many of the other arcane tax abatements built into New York’s complex development world, 421-a gives the city leverage and bargaining power with the private sector when it comes to convincing developers to create affordable housing, pay non-union workers higher salaries, and other nuances of construction.

Those who hate it (be them activists, tenants or the general public) complain that private developers don’t hold up their end of the bargain — overcharging tenants in units they are required to keep affordable among other deceitful practices, and that the city is losing valuable tax money that could be used for much-needed infrastructural improvements.

Furthermore, they contest that the abatement is archaic, and the city no longer needs to incentivize developers like they did in the ’70s. In 2014 alone, the city forfeited $1.1 billion in tax revenue from the 421-a program. That same year, 60 percent of the buildings the abatement subsidized were in Manhattan.

Who loves 421-a? Developers and affordable housing advocates.

Developers reap the majority benefits of the tax break, which enables them to save money on taxes while meeting (or skirting) the abatement’s light requirements.

Mayor de Blasio is also a strong proponent of the abatement continuing, as 421-a enables him to more easily achieve his affordable housing goals, if at a high cost.

Will 421-a turn into a pumpkin at midnight?

The abatement was renewed in June of 2015 with a slightly higher percentage requirements for affordable units (25-30 percent, as opposed to the former 20 percent) and the condition that the Building and Construction Trades Council — representing the city’s unions — and the Real Estate Board of New York, would come to an agreement by January 15 about whether or not workers at 421-a developments will get a prevailing wage.

The construction unions want subsidized buildings to pay union-level wages to workers. But the Real Estate Board argues that doing so would increase construction costs by 20-30 percent, according to the New York Times.

Update: the 421-a tax break officially expired on January 15, 2016.

The Real Estate Board of New York and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York did not come to an agreement about construction workers’ wages at 421-a developments.

The expiration of this tax credit represents the end of an incentive program that allowed the city significant leverage in private development, including mandating affordable housing and non-condominium construction.

Reports from the NYU Furman Center are corroborated by REBNY officials who predict the incentive’s expiration will be detrimental to the creation of multi-family residential development in the city.

Still, REBNY and BCTCGNY have both issued statements noting they are open to continuing the discussion regarding 421-a. Indeed, this is not the first time the tax credit has expired, and if an agreement is reached in the future the program could potentially be resurrected.

What does expiration mean?

No new developments will be able to qualify for the tax break. Not-yet-built developments that qualify for 421-a and have already done their paperwork will maintain the conditions of their agreement with the city, and developments which are currently enjoying tax-freezes under the exemption will be able to continue do so for however many years they were slated upon qualification.

No development that has reaped the benefits of 421-a is going to have to pay back taxes.

But new developments would not be able to receive the lucrative tax breaks that have helped boost building over the past few years — and many believe that development overall will slow dramatically, perhaps catastrophically.

The expiration could be a significant hurdle to the mayor’s ambition of building tens of thousands more affordable units over the next decade — eight percent of the more than 40,000 affordable apartments created or preserved by Mayor de Blasio in the past two years were generated by the 421-a program.

But what do you think? Is the 421-a expiration a good thing for the city? Or will it put the kibosh on development?

Related Stories

Brooklyn Landlords Dodge 421-a Requirements

Extending 421-a: Does It Matter?

As Condo Sales Languish, Builders Slam 421-a Reform

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

[sc:daily-email-signup ]

If the Real Estate Tax assessment process of building new construction, or just improving existing buildings was more transparent and workable without the need for the tax abatement s it would make it much easier to work out the real cost of building.

But giving away millions of tax revenue in order to create so little “affordable” housing seems to me to be an easy sound bite for Politicians to say they are doing something without actually doing much to remedy the bigger issue of outdated Real Estate Tax assessments.