Brooklyn Mental Health Advocates Speak Out About Involuntary Hospitalization Policy

Two months after Mayor Eric Adams announced a new policy expanding involuntary hospitalizations of homeless and mentally ill New Yorkers, Brooklyn-based mental health advocates are hoping a more comprehensive and compassionate approach is possible.

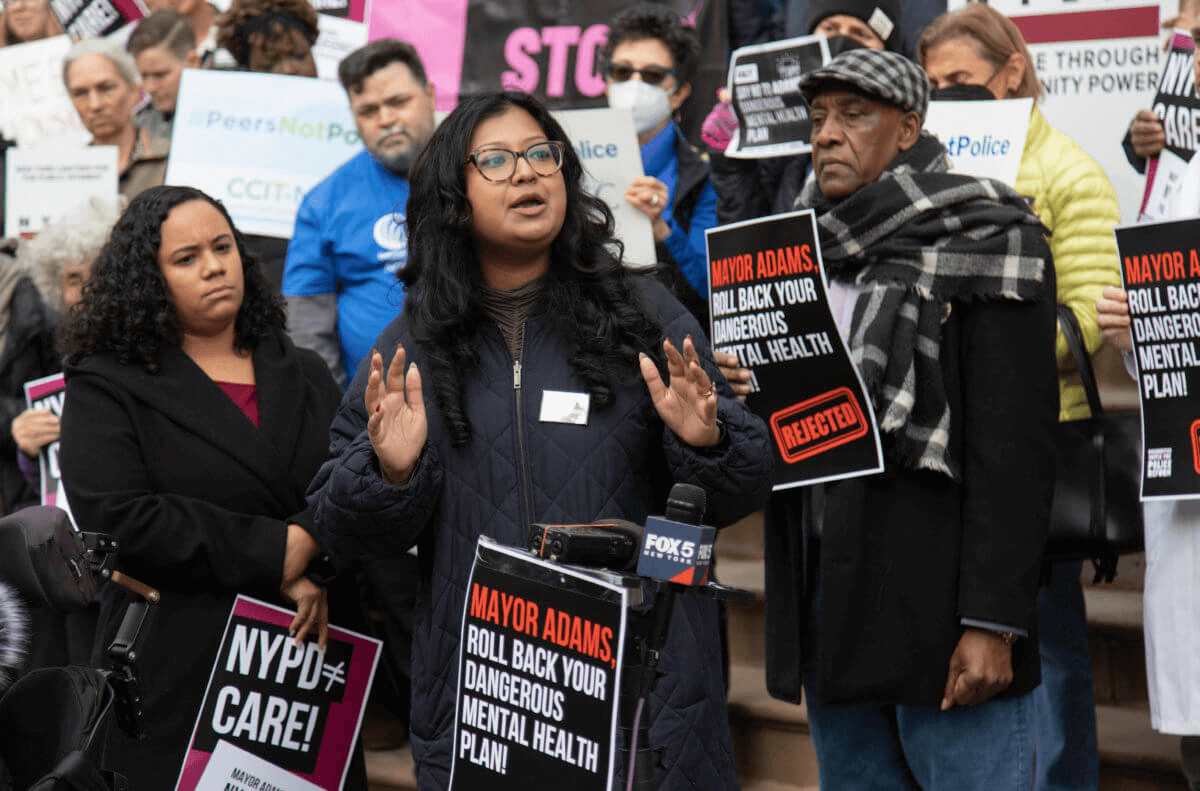

Advocates and people who have been involuntary hospitalized said they feel the policy is a “band-aid” solution for a much larger and more complicated issue. Photo by John McCarten/NYC Council Media Unit

Two months after Mayor Eric Adams announced a new policy expanding involuntary hospitalizations of homeless and mentally ill New Yorkers, Brooklyn-based mental health advocates are hoping a more comprehensive and compassionate approach is possible.

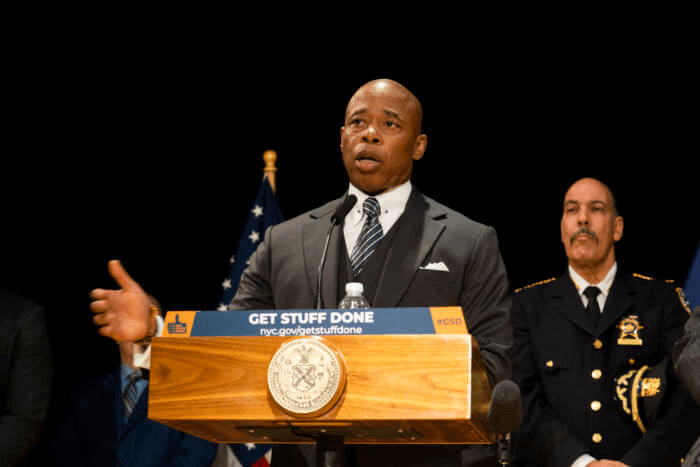

In late November, Adams announced that first responders and members of the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene would have the authority to commit someone who “appears to be mentally ill and displays an inability to meet basic living needs, even when no recent dangerous act has been observed” to the hospital. Previous policies authorized police or licensed medical professionals to involuntarily hospitalize someone only if they were acting in a way that presented a threat to themselves or others.

The announcement immediately garnered criticism from advocates and elected officials, who said the directive was dangerous and ineffective. Many in Brooklyn and the rest of the city agree that there needs to be more of a focus on the mental health and homelessness crises — but that focus must be guided by those who would be affected by the policy and their supporters. Ahead of a February 6 oversight hearing examining the policy, advocates and elected officials rallied against the policy.

‘It’s all about out of sight, out of mind’

“It adds to a stereotype; it adds to the criminalization of people who may have a mental health diagnosis,” said Tim Clune, executive director of Disability Rights New York. “And when you look at what he’s talking about, what this policy will do and these directives, it’s to remove people. It’s all about out of sight, out of mind, they don’t want to see people who have mental health diagnoses on the streets.”

In a statement released in December by the NYC Progressive Caucus, three Brooklyn city council members — Shahana Hanif, Lincoln Restler, and Jennifer Gutiérrez — said the initiative is one of many “band-aid solutions to chronic challenges” proposed by the mayor.

“He is focused on superficial efforts to get issues out of sight,” the statement reads. “But is failing to invest in expanded inpatient and outpatient behavioral healthcare capacity and supportive housing.”

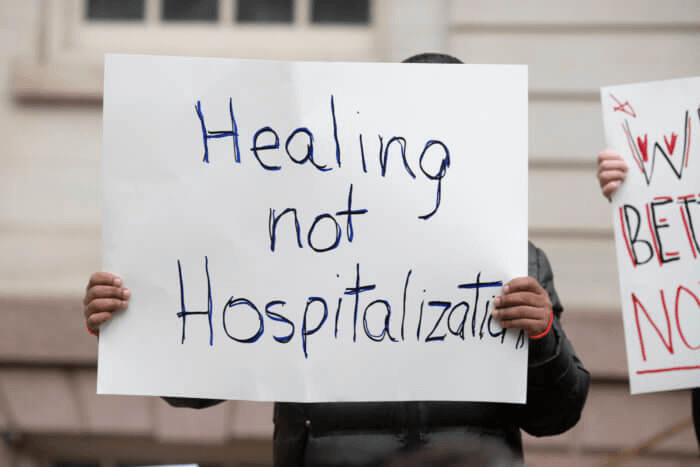

The council members said more funding and support is needed for supportive housing and long-term inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care — short-term emergency hospitalizations do little to address long-term mental health issues.

“This cannot be solved overnight or in one year,” said Janelle Farris, the CEO of Brooklyn Community Services, which provides mental health services, outreach, and temporary housing. “There needs to be increased funding and support for the entities that help that population. This is coming up with short-term band-aids when we need surgery.”

Matt Kudish, executive director at the New York City chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness chapter, said he was glad to see the mayor paying attention to mental health, but wasn’t sure the approach was correct.

“This plan is ill conceived and is not going to keep people safer,” he said.

What Kudish hopes to see is the mayor bring mental health advocates together to discuss this ongoing issue with a long-term solution.

“NAMI would be willing to meet with the mayor’s office,” he says. “We hope that they would initiate an opportunity for entities that are deeply rooted in these issues, who can bring years of knowledge and experience to bear to develop a comprehensive plan that can more meaningfully and more positively affect the lives of those living with mental illness.”

Judy B., a lifelong New Yorker and member of the Fountain House, a nonprofit social rehabilitative program for those with mental illness, which Adams visited in July, said she is most concerned about how city workers who are not specially trained in mental health and homelessness would treat those they feel should be hospitalized.

“Not everybody who has mental illnesses is homeless, and not everyone who is homeless is mentally ill,” she said. “How does this mayor take it upon himself to think that anybody [can be] a judge about who could take care of themselves or not on the street. If you sweep somebody off the street, and you then put them in a hospital to be evaluated, yeah, anybody who’s living on the street is going to be showing signs of trauma.”

Judy, who is being treated for depression and has some tendencies of bipolar disorder, was once involuntarily hospitalized and said the experience was traumatizing. One of her sons was also hospitalized only to be released without no place to go but the subway trains, which he rode for several days. She feels no one should experience being discharged with no place to go and no one to care for them.

“The whole root cause is to have more affordable housing, more supportive housing, and more resources for people who are going through trauma,” Judy says. “Trauma of being fired from a job or being evicted from their place, or not being able to afford to pay their bills.”

Pols speak out against involuntary hospitalization at oversight hearing

Following Monday’s hearing, some have hope that change is on the horizon. Brooklyn Council Member Charles Barron spoke during the rally while heading inside City Hall, addressing Adams as “Mayor Cop.”

“All the pressure that you are putting the city under, particularly Black and Brown neighborhoods,” Barron said. “If you had to deal with the poverty our people had to deal with, the unemployment that our people have to deal with, if you had to deal with everyday living that our people go through, you might be out there out of your mind as well.”

Barron also called out some of his colleagues who had spoken out against the directive, but indicated that they would vote for the upcoming city budget that is likely to cut funding for housing, education, and healthcare.

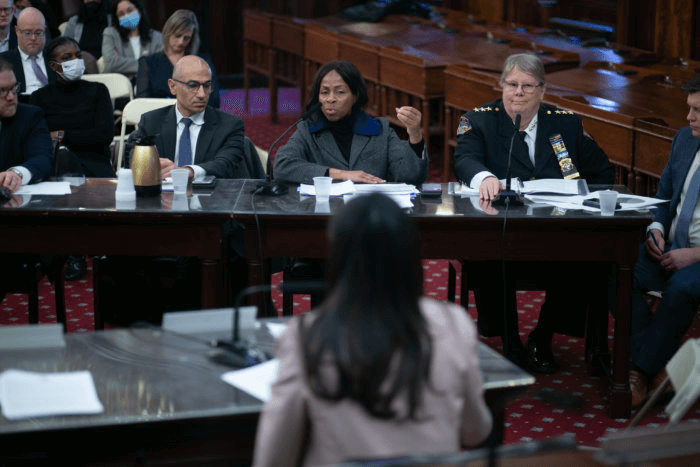

During the oversight hearing, which was held jointly with the Committee on Mental Health, Disabilities, and Addiction, the Committee on Fire and Emergency Management and the Committee on Hospitals, Hanif spoke of the City Council’s need to look into issues affecting many New Yorkers.

“I’m glad our council is fulfilling our oversight responsibility to investigate this legally dubious and inhumane directive,” she said during the hearing. “I, along with dozens of my progressive colleagues, have been clear since the first day of this announcement that this plan is far from the solution our city needs. We need investments in care, housing, and jobs – not committing people to hospitalization against their will.”

Two new bills were introduced during the hearing — one that would require additional training on engaging with people with autism for law enforcement, while the other creates a city-run online mental health services portal.

Adams defended the directive when asked about the hearing by NY1.

“This is a humane program that’s not being led by police officers, it’s being led by mental health professionals,” the Mayor said.”It is not something for anyone who’s dealing with a mental health issue, it is an individual who has reached a level that they cannot take care of their basic needs and they’re in danger to themselves.”

Even so, mental health advocates who are hoping he continues to focus on solving the problem will do so with more long-term plans involving teamwork.

“I think [the administration] won’t be able to come up with a plan to address the crisis and solve the problems by themselves,” Kudish says. “I think they need to lean on the breadth of experience that exists in the field of organizations that are providing mental health services and homeless services in the community. But I think it’s not going to be one initiative. It has to be comprehensive and it must recognize that there’s a continuum.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- Actor Gbenga Akinnagbe, Local Pols Ask Public to Help Save Bed Stuy’s Magnolia Tree Earth Center

- Crown Heights Tenants Launch Rent Strike Over Living Conditions

- Fearing Displacement, Coney Island NYCHA Tenants Protest Privatization Plan

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment