A Breath of Fresh Air: A Short History of the Sleeping Porch

The early twentieth century fresh-air movement spurred an architectural trend of sleeping porches as an essential domestic amenity.

A 1922 ad for Armstrong linoleum in Ladies Home Journal.shows a dressing room and adjacent sleeping porch with a continuous “modern linoleum” floor installed over sound-deadening felt. Collection of Susan De Vries

The early twentieth century fresh-air movement spurred an architectural trend of sleeping porches as an essential domestic amenity. Brooklynites embraced the fully windowed rooms, said to ensure healthy sleeping and prevent disease. In scientific journals and the latest home decorating and architecture magazines, writers explored the benefits of year-round fresh-air sleeping and the design of the rooms.

Part of the push behind the touted health benefits was the reality that fresh air and rest were, at the time, the modern treatments for tuberculosis, earlier known as consumption. In the late 19th century, the bacteria behind the disease was discovered and it was proved the disease was contagious but preventable. However, there was no medicinal treatment until the development of antibiotics in the mid 20th century. Until then, sanatoriums, like those that opened in the healthy climes of the Adirondacks in Saranac Lake, N.Y., or hospitals within the city such as the Brooklyn Home for Consumptives, offered fresh-air cures and charity organizations battled the unhealthy conditions that spread the disease. In 1908, the Committee on the Prevention of Tuberculosis of the Brooklyn Bureau of Charities estimated that one in every 10 deaths in the borough was due to the disease.

Domestically, the benefits of invigorating air for a germ-free sleeping experience led to the construction of sleeping porches for those who had the space or window sleeping tents, portable rooftop bedrooms, simple tents and other contraptions for those who didn’t. By 1909 a substantial article in the magazine Country Life in America declared “the practice of outdoor sleeping has become too general to be dismissed from consideration as a fad.” Enthusiasts declared that taking to their beds in the open air banished ailments from colds to insomnia and had to be an improvement over sleeping in artificially heated rooms.

Brooklynites who were purchasing newly built houses in neighborhoods carved out from farmland often had the option to include a sleeping porch in the plans. Local advertisements for new homes in the early 20th century frequently listed a sleeping porch as an up-to-date amenity alongside electric lights and sanitary plumbing. For existing homes, adding a sleeping porch to the rear or side was a popular update in the teens and 1920s.

Because the goal was to get as close to the healthy air as possible, upper-story sleeping porches were seen as most beneficial. In Brooklyn in the early twentieth century, this typically meant on the second floor of a two-story wing. The fully windowed room was typically reached via a bedroom, with French doors separating the two. The bedroom served as a warm area for dressing before stepping into the brisk sleeping space.

While magazines supplied all manner of plans for complicated folding and hanging beds, a simple iron cot was likely more common for most modest Brooklyn porches. Other furnishings would have been minimal and lightweight, making it easier to move beds about as needed. Floors would be hygienically covered in easily cleaned and relatively waterproof tile or linoleum. Ceilings were frequently made of varnished wooden bead board, a treatment typical for regular porches of the period as well as perhaps invoking a bit of a rustic cabin aesthetic. Windows could have screens for summer and storm sashes for winter, but the most important feature was that they be fully operable to let in the maximum amount of fresh air. Sliding and casement windows (some hinged at the top) were popular. Roll-up blinds, available in sunfast materials and weather-fast finishes from such stores as Brooklyn’s Frederick Loeser & Co., would provide a bit of sun protection during the day.

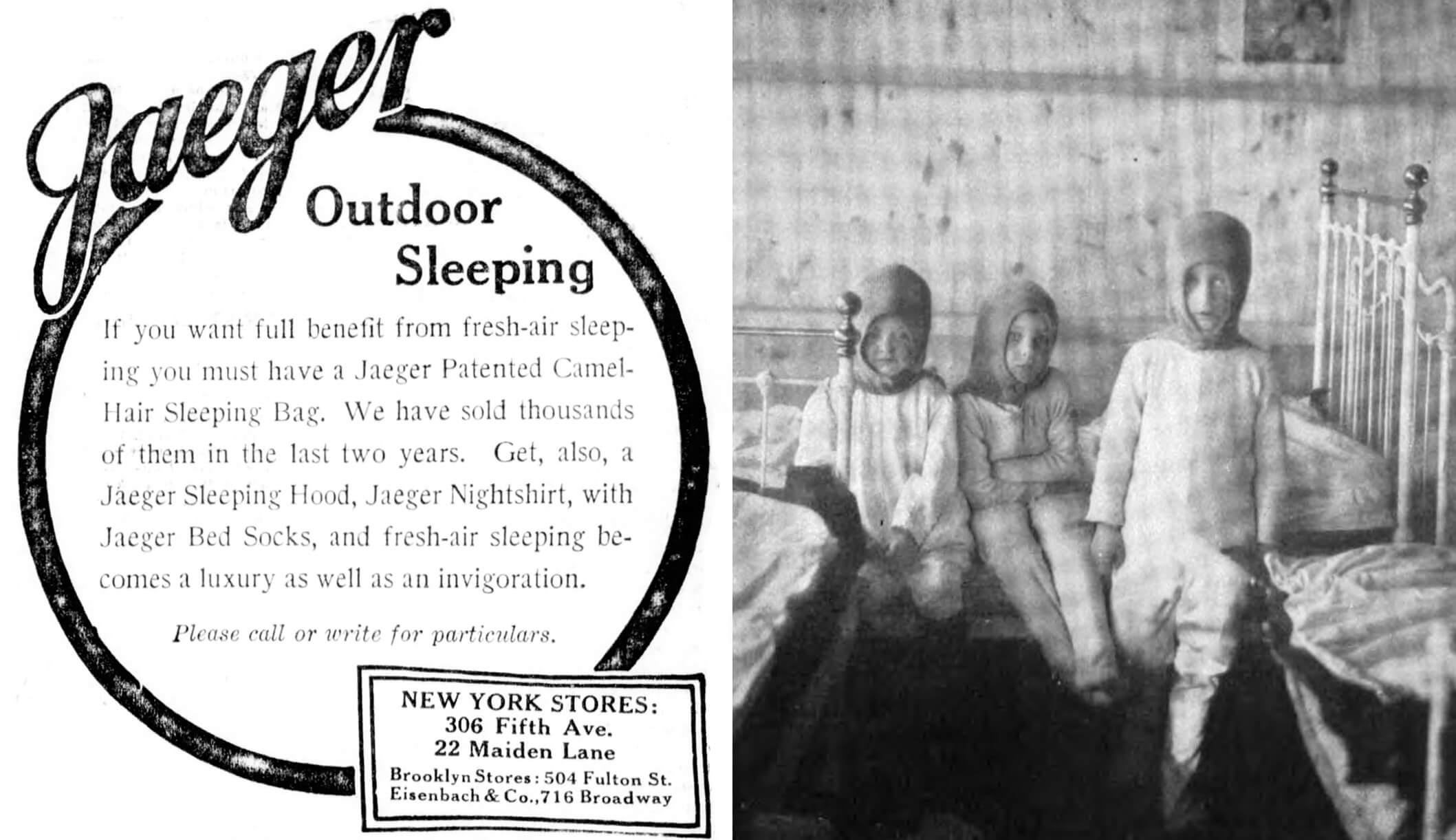

For the dedicated winter sleeping enthusiast, sleeping hoods, bed socks and camel-hair sleeping bags could be purchased at Jaeger’s in Downtown Brooklyn, which promised “fresh air sleeping becomes a luxury as well as an invigoration” with their warm togs.

As medical treatments became a reality and the fashion of sleeping outdoors in one’s own home faded, many porches, particularly in space-starved areas like Brooklyn, were renovated to become more fully weatherized and turned into bedrooms or living space. A walk through neighborhoods such as Windsor Terrace, Prospect Lefferts Gardens and Flatbush reveals glimpses of rear extensions with second-story rooms, some still fully wrapped in windows while others were filled in and perhaps insulated. Original ceilings often disappeared under dropped tiles, but a peek above might uncover an intact wood finish.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- A Guide to Understanding and Maintaining Historic Brick in Brooklyn

- Lighting in the 19th Century Row House

- 10 Tips for Restoring a Wood Frame House in Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment