A Guide to Understanding and Maintaining Historic Brick in Brooklyn

Here, a brief history of brick in the borough of homes and churches and tips for keeping vintage masonry in good condition.

Narrow golden brick and terra-cotta ornament an 1890s house in Bed Stuy. Photo by Susan De Vries

One of the pleasures of walking Brooklyn’s streets is seeing the glorious brickwork in all its many hues, shapes, textures and patterns. Here, a brief history of brick in the borough of homes and churches and tips for keeping vintage masonry in good condition.

“No matter the size of a brick building, you can always see evidence of the craftsmanship, you can relate to its human scale, and you immediately understand that it was built by hand,” said Brendan Coburn, founder of CWB Architects, and an expert on Brooklyn’s 19th century brick buildings.

Bricks typically came from the Hudson Valley, a center of brickmaking in the 19th century thanks to abundant clay on the banks of the Hudson. Early bricks were handmade; advances in brickmaking and firing led to stronger bricks over the years, particularly after the 1870s. It was standard practice to use poorer quality bricks for rear walls and high quality bricks for front facades in Brooklyn at least as late as the 1890s.

Brick in Federal houses, such as some 1820s examples still standing in Brooklyn Heights, was typically laid in the Flemish bond pattern, which alternates the short and long faces of the brick. While plain running bond has endured since the Greek Revival came into fashion in Brooklyn from the 1830s through the 1850s, in the last quarter of the 19th century, there was an explosion of variations in color, texture, shape and pattern. In the 1890s, dark red, brown, orange and yellow brick created picturesque streetscapes, and were superseded just a few years later by paler shades, including gray and cream. In the early 20th century, variegated and brown hues as well as decorative clinker bricks emerged. A style known as tapestry brick covered facades with geometric patterns such as diamonds and basketweave using two or more colors of brick, such as brown, dark gray and cream.

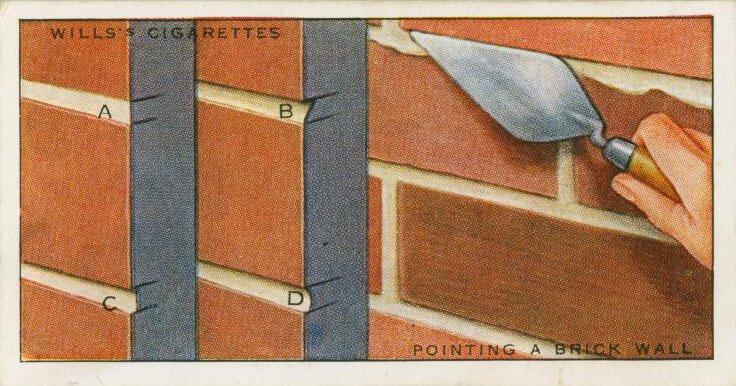

Ideally, brick facades will be maintained using the same materials. The older the brick, generally the softer it is, and modern mortars will cause it to deteriorate. When repointing brick to replace crumbling mortar (typically needed every 20 to 40 years) on an older building, ideally the original mortar will be tested in a lab and custom mixed to get precisely the right combination of strength, texture and color. But if lab testing is not possible, use a weak type-N mortar, advised Coburn.

If one or more bricks need to be replaced, it is possible to have an exact match custom made. ConSpec Associates of East Haven, Conn., for example, can make as few as five to as many as 10,000 or more bricks for historic restorations. There is a $50 fee for matching and typical prices start around $10 a brick for fewer than 30 units but in large quantities the price “drops dramatically,” said ConSpec president and historic masonry expert Patrick Morrisey.

Painting brick or adding a clear waterproof coating — even one formulated to be breathable — is generally not advised because it can trap moisture and cause the brick to deteriorate, according to the National Park Service’s preservation guidelines. One exception is structures built with weak brick before the mid-19th century that were intended to be protected with natural, breathable milk paint or lime-based whitewash.

[Photos by Susan De Vries]

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2021/22 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Building a Borough: The Brick Buildings of Brooklyn

- 10 Tips for Restoring a Wood Frame House in Brooklyn

- Lighting in the 19th Century Row House

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment