Slee & Bryson: Architects for the Modern Age

The firm’s unassuming but numerous buildings changed the look of Brooklyn.

Albemarle Terrace. Photo by Susan De Vries

Ever since architecture became a legitimate and fast-growing profession in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, Brooklyn has had its superstars. They were men (without exception) such as Montrose Morris, George P. Chappell, Theobald Engelhardt, and the Parfitt Brothers, who painted on the canvas of the city. They, and many others whose biographies have been featured on Brownstoner over the years, created much of the Brooklyn many of us treasure today. They designed our houses and apartment buildings, churches and synagogues, and our civic, commercial, and industrial buildings.

They and their contemporaries began designing in the 1870s and ‘80s, and many had retired or died by the end of World War I. They paved the way, both in design and in their business practices, for the generation that came after them, firms and individuals that started work in the new century. One of the most important of these early twentieth-century architectural firms was Slee & Bryson.

John B. Slee and Robert H. Bryson

John B. Slee was born in Maryland in 1875. He was educated at the Friends School of Baltimore. Between 1891 and 1893, he received his architectural training at Baltimore’s Maryland Institute, one of the country’s oldest art and technical schools. He moved to Brooklyn sometime after graduation and was employed at an architectural firm, perhaps Kirby, Petit & Green. The 1900 census shows Slee working as a draughtsman and living as a boarder with his younger brother George at a house at 183 Amity Street in Cobble Hill.

Robert H. Bryson was also born in 1875, but in Newark, N.J. His family moved to Brooklyn and lived in several locations within the Bedford section. In 1892, his father, Robert, was listed as a machine inspector. He was educated in Brooklyn, and by the 1900 census, was still living at home and also working as a draughtsman.

Both men may have been working for architect John J. Petit, a partner in the firm Kirby, Petit & Green. The firm was making a reputation for itself, mostly on the strength and imagination of Mr. Petit. The group designed residential and commercial buildings in various neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Petit was the chief designer of former Senator William H. Reynold’s Coney Island amusement park called Dreamland. He was also one of the architects creating the new suburban neighborhoods in what we now call Victorian Flatbush.

Beginning in the late 1880s, Petit had been working with developer Richard Firkin. His enclave called Tennis Court was the first suburban neighborhood in Flatbush, located near the Prospect Park Parade Grounds. By the time Slee and Bryson may have been working for Kirby, Petit & Green, Petit was named the chief designer for Dean Alvord’s much more ambitious and upscale Prospect Park South, just next door.

Petit was quite busy designing his eclectic masterpieces for Alvord, along with his work for other Flatbush developers, so he gave his draughtsman a shot at designing in Prospect Park South, as well. John Slee partnered with another architect named Henry La Pointe for five houses, while Robert Bryson paired with another area architect, Carroll Pratt, on three houses. Slee designed seven houses on his own, and Slee & Bryson were partners in 1905 when they designed ten more, the last one in 1927.

John Petit was only five years older than Slee and Bryson, and in addition to being their boss and mentor, he was also their friend, and travelled in many of the same social circles. In 1898, John Slee’s cousin Susan Perrin Martin married Edward Cole Howe. Petit was the best man and Slee was an usher.

Slee & Bryson went into partnership in 1905, with offices at 154 Montague Street, a large Italianate brownstone long converted into a storefront with offices above. They hit the ground running with commissions in Prospect Park South and other growing suburban Flatbush developments, as well as commissions throughout the brownstone neighborhoods and southern Brooklyn.

Their work ran the gamut of residential styles. They designed wood frame houses of various sizes and for various incomes everywhere from Flatbush to Bay Ridge. They designed apartment buildings, garages, additions and alterations, the bread and butter of most architectural firms, especially when first starting out. And they designed hundreds of brick houses.

Slee & Bryson – the Arbiters of Colonial and Tudor Taste in Brooklyn

By about 1910, America was firmly in love with Colonial and Tudor architecture. The interest in Colonial-era life and architecture really started back at the nation’s centennial, in 1876, but it died down until it took off again at the turn of the new century. As cities were expanding and new suburbs were being created, Americans wanted an architecture that was truly ours. The impressive Beaux-Arts marble masterpieces were great for libraries and train stations, but ordinary Americans wanted to live in American-style homes.

The Colonial Revival style, a combination of British Georgian and American Federal, brought symmetry, order, and a classical elegance to the new homes. Toss in Dutch Colonial elements such as gambrel roofs, and you had a quintessential American home. It could be built in wood or good American red brick.

Ironically, around the same time, America also fell in love with Tudor and Medieval-inspired architecture. This was about as European as you could get, but half-timbered homes were soon popping up in the new commuter suburbs as the new must-have American home. The style was nicknamed Stockbroker Tudor due to its popularity in upscale suburban counties like Westchester. In the city, architects were designing six-story apartment buildings as well as suburban homes with stucco and half-timbered details. Slee & Bryson designed some of the earliest and best in Prospect Park South and elsewhere.

Most Brooklynites who are aware of Slee & Bryson remember them for their brick houses. They are quite prominent as both row houses and detached and semi-detached homes in Prospect Lefferts Gardens and the Albemarle-Kenmore Terraces Historic District in Flatbush.

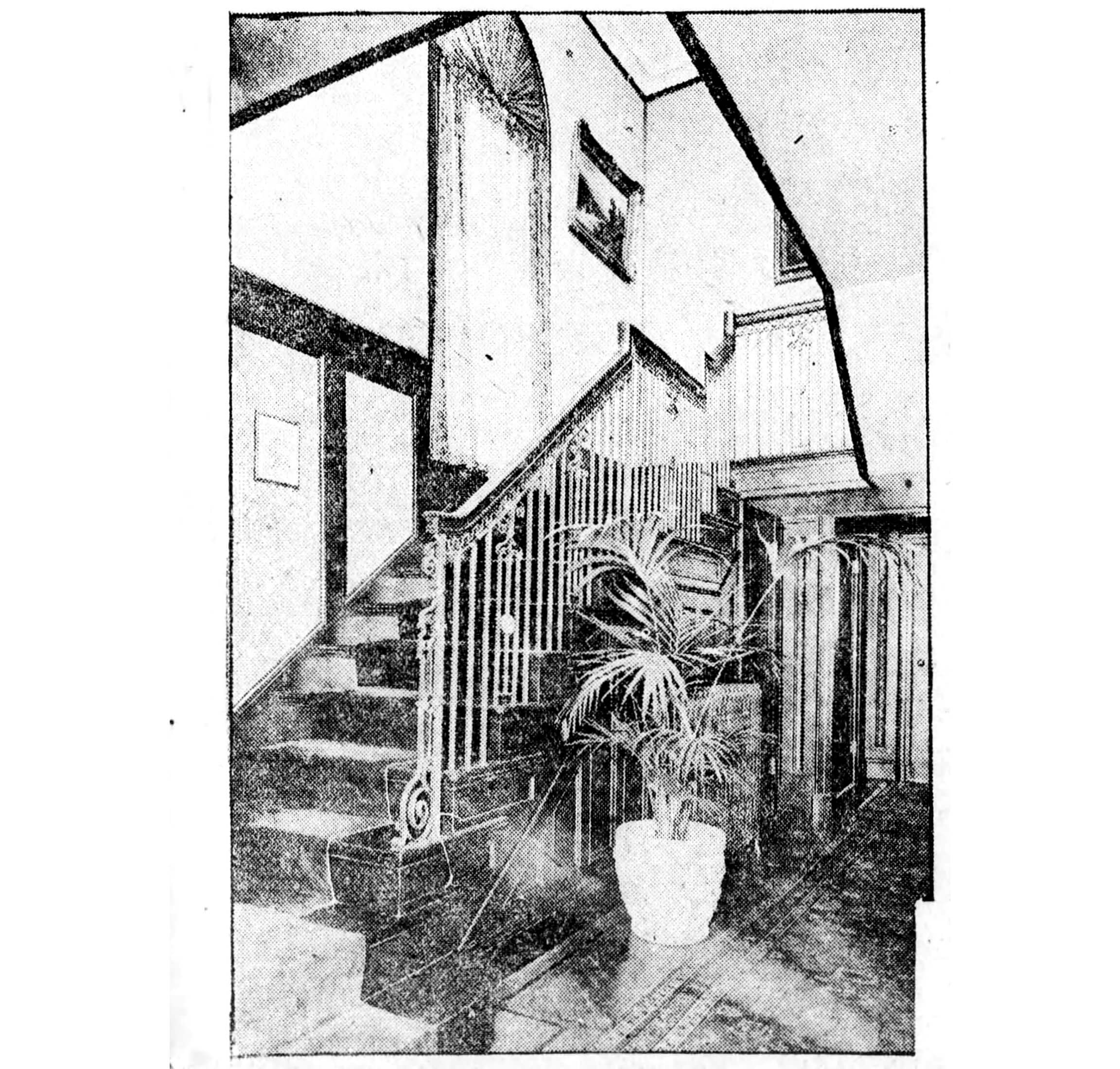

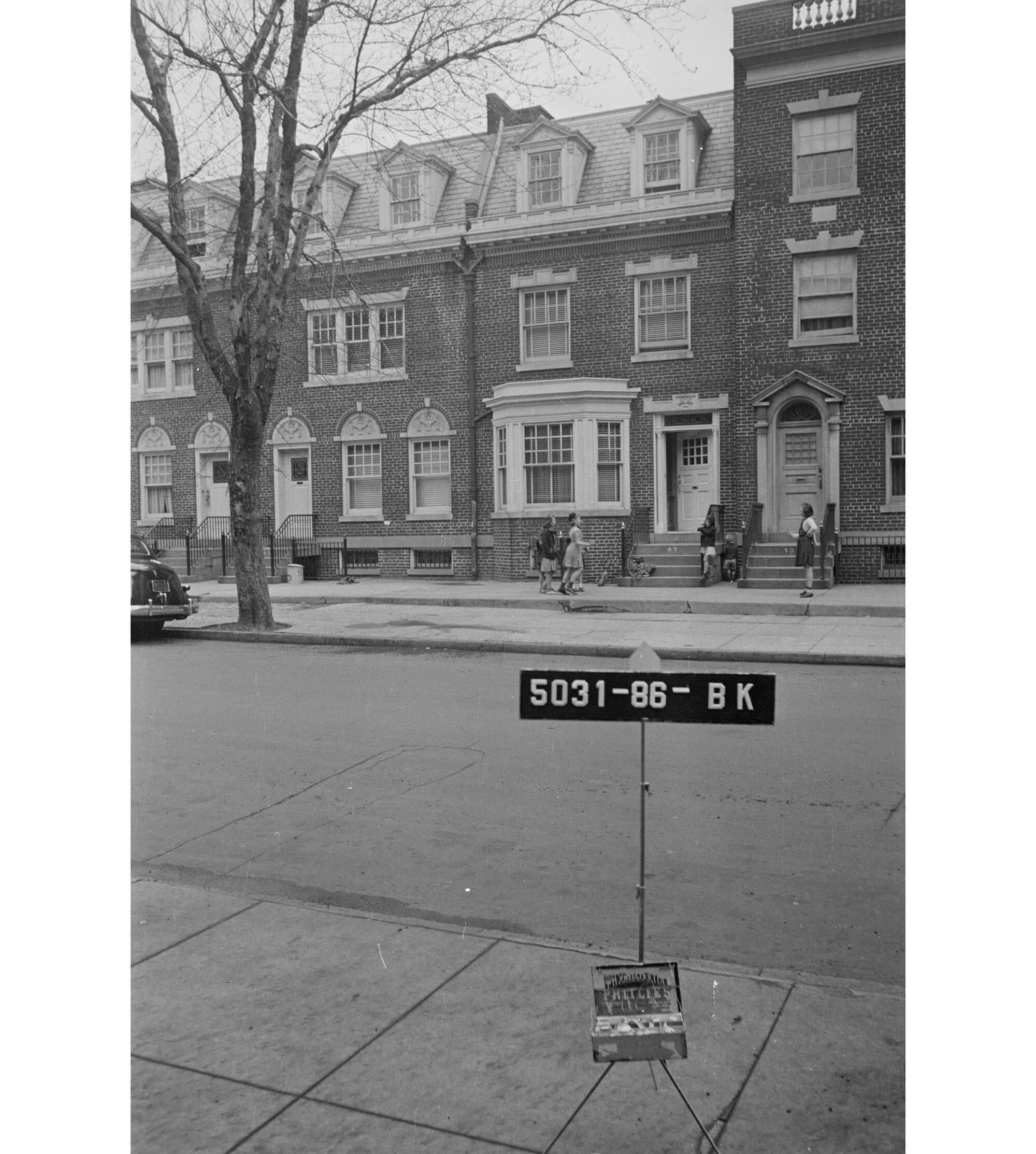

Slee & Bryson designed the entirety of the latter, which consists of two short cul-de-sac parallel streets off the beaten track near 21st Street, a block away from Flatbush Avenue and the Flatbush Reformed Church. The houses were all built between 1916 and 1917 for developer Mabel Bull, who sold all of them by the end of 1918. They are all classic red-brick Colonial-style houses with white limestone and wood trim. Some have Palladian windows and most have twin mansard roof dormers, keystone lintels and six-over-six windows. The houses on Kenmore Terrace were built with attached garages in the front, while those on Albemarle have a service alley with garages.

It is thought that Bull gave the duo the commission after seeing the brick Colonial group they had recently finished not far away in Lefferts Manor, a grand row of 14 Colonial houses at 23-49 Midwood Street, which were built in 1915. Both groups are modeled on the architects’ first row of this kind, which were built in 1913 and can still be found at 1329-1337 Carroll Street, in what is now Crown Heights South. A much smaller group of similar houses can also be found on St. Marks Avenue in Crown Heights North. They were built in 1919.

Slee & Bryson also designed one-offs and smaller groups of houses in other neighborhoods. Their Colonial brick houses, plain and fancy, can be found in Park Slope, Brooklyn Heights, Lefferts Manor, Stuyvesant Heights, Bay Ridge, Midwood, East Flatbush, Crown Heights North and South, Clinton Hill, Kensington and more.

They Were Everywhere

In fact, Slee & Bryson were ubiquitous, making them more prolific than almost all of their predecessors, even men like Amzi Hall and Axel Hedman, both of whom each designed hundreds of buildings in the late nineteenth century. The Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide was a weekly trade periodical that listed most of the building going on in New York and surrounding areas, primarily in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Between 1905 and 1922, when it ceased publication, there are 495 entries for Slee & Bryson, plus more for each individually or with someone else. Many of those entries are for multiple buildings in one permit.

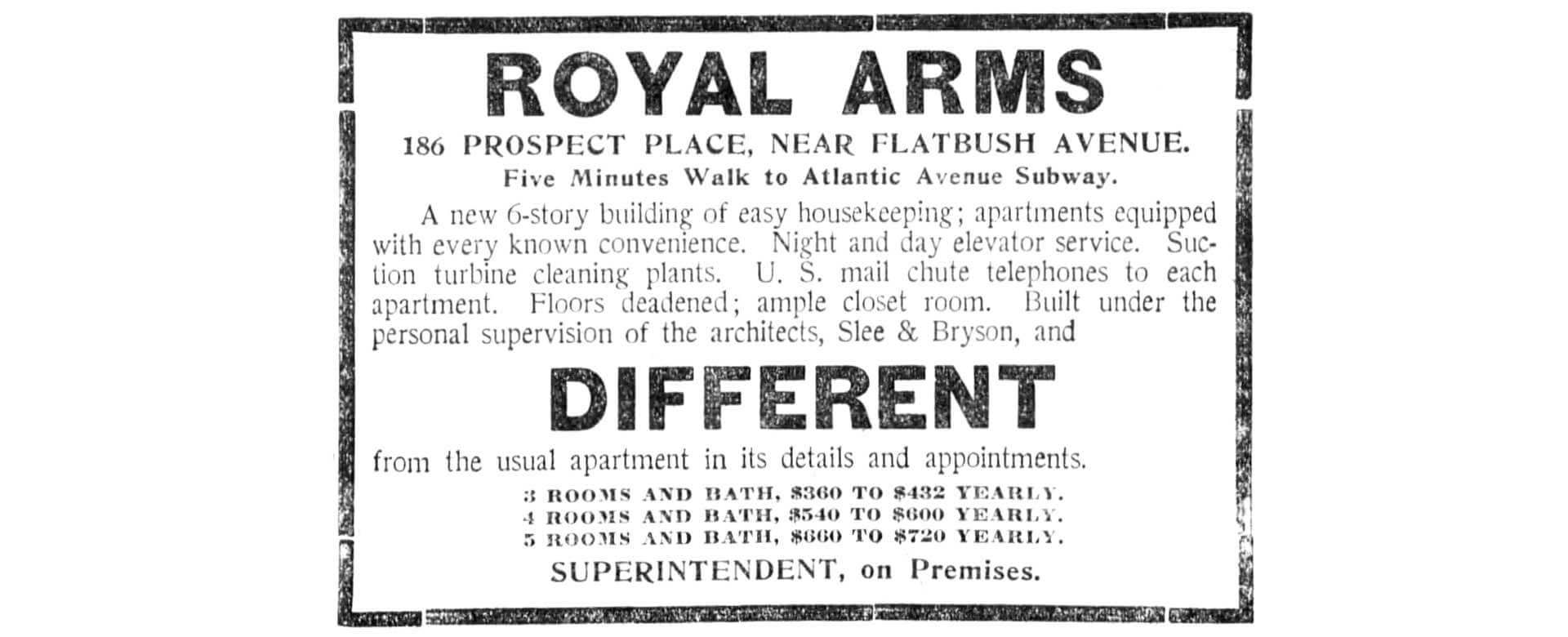

The duo was just hitting their stride in 1922, so it would not be surprising if they were responsible for at least a thousand separate buildings in their careers. A look through this list as well as entries in the Brooklyn Eagle reveals that in addition to single or two-family homes, Slee & Bryson were also responsible for many of the six-story elevator apartment buildings that went up in almost every Brooklyn neighborhood in the years between about 1910 and 1925. Slee & Bryson apartment buildings can also be found in Riverdale, Manhattan and Staten Island.

Many of these buildings are not works of genius or great beauty. They were sturdy, brick apartment buildings, most vaguely Colonial Revival, built to house a growing middle class population. Some are so plain as to go unnoticed, like 450 Clinton Avenue. Others, like 1144 Bergen Street in Crown Heights North have some Flemish Revival panache. In Brooklyn Heights, 8 Remsen Street, with very little Georgian detail left today, was originally only four stories tall, and was specifically designed for its owner, Bruce Duncan, who wanted only four luxury apartments in his building, all with magnificent harbor views.

As the lifestyles of people in Brooklyn changed in the twentieth century, Slee & Bryson were most adaptable. Both men were very active in Brooklyn’s clubby architecture world. Both served as president of the Brooklyn chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and Slee also served as treasurer in 1915.

Bryson married Charlotte Stoddard in 1915. John Slee was his best man. The Brysons would go on to have two children and eventually settled in Bay Ridge. This part of Brooklyn was very popular with well-to-do people in the years of expansion before the Depression, with Shore Road and any land overlooking the harbor being especially prized. Bryson purchased property near Owl’s Head, which is a city park today, and planned to build a house. He ended up selling that plot and built another home nearby. The company became quite active in home design in the area soon afterwards, designing both substantial suburban homes and more modest housing in the area. Bryson and Slee also designed a new country house for the Crescent Athletic Club located along Shore Road in Bay Ridge.

Slee never married. He settled in Brooklyn Heights, and lived at 102 Pierrepont Street, a rather unassuming row house that he shared with his sister Leticia until her death in 1922. Around this time, Slee became a vocal proponent and authority on the adaption of traditional one-family row houses into small apartment buildings. He wasn’t alone in this; his contemporary J. Sarsfield Kennedy was also advocating turning “old fashioned” 19th century row houses into modern 20th century apartment buildings.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle published several articles about Slee’s stratagems, complete with floor plans. They showed building owners that by stripping the front ornamentation, getting rid of the stoops, and moving the entrance to the ground floor, one could divide the houses into floor-though apartments, while modernizing them with the latest Colonial Revival interiors. Those old buildings could approximate the modern new apartments, many designed by Slee & Bryson, that were now so popular in Brooklyn Heights and elsewhere. Slee may have taken his own advice, as 102 Pierrepont no longer has a stoop and was subdivided into six units.

A Fine End to Two Long Careers

Slee’s and Bryson’s careers may have been slowed down by the Great Depression, as were many, but they continued to design through the lean years, contributing more apartment buildings, homes, clubhouses and other buildings. The building that made them a household word in Brooklyn came at the end of their joint careers. It was a modern new building for the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, located on Monroe Street in Brooklyn Heights.

The elegant courthouse was begun in 1936 and finished a year later. It is one of their best designs. It was the best of Brooklyn’s newer courthouses, housing at its opening eight justices and 63 staff. The location and civic pride evidenced in the Appellate Court was cited as one of the factors in the decision to not run Robert Moses’ Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through Brooklyn Heights a decade later.

By 1936, the Bryson family had moved back to Brooklyn Heights. Robert Bryson wasn’t well, and after a long illness, died on September 10, 1938 at his apartment at 15 Clark Street, a building he and Slee designed. He was 63. Slee kept the firm’s name and he and his staff kept going. They had moved to larger offices at 16 Court Street, where most of Brooklyn’s architects hung their hats. They still had plenty of buildings left in them.

In 1941, Slee was chosen to lead a panel of architects, city planners and others to contemplate a new civic plaza near Borough Hall. He threw himself into the project, giving lectures and presentations and publishing his maps and ideas in the Brooklyn Eagle. Robert Moses wanted to tear down the area around Borough Hall and create a Venetian-style civic plaza. Slee designed an elegant street plan, complete with new buildings. Some aspects of his proposal were incorporated into Cadman Plaza, although his version would have had much more parkland.

Slee continued to work until his death, on January 14, 1947. He suffered a heart attack and died at Methodist Hospital in Park Slope. He was 71. He left behind three siblings. He and Bryson, in their quiet, unassuming way, contributed more to the built fabric of Brooklyn than most – hundreds upon hundreds of buildings, many of which are still with us. That’s an impressive legacy.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2019/20 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Brownstone Bible Redux: Charles Lockwood’s Seminal New York Row House Book Gets an Update

- Coney Island on My Mind: A Brief History of Brooklyn’s Waterfront Playground

- The Story of Brooklyn’s Grand Stage, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment