The Story of Brooklyn’s Grand Stage, the Brooklyn Heights Promenade

Tourists and locals alike enjoy one of the greatest views in the entire city from the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

The Brooklyn Heights Promenade under construction, 1949. Photo from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle via Brooklyn Collection, Brooklyn Public Library

It is almost impossible to watch a television show or movie set in Brooklyn without encountering a scene set on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. Whether it features heartbroken characters leaning on the railing with Manhattan as their backdrop or chase scenes along its length, the promenade is the perfect setting. With iconic brownstones in the background and the harbor, Statue of Liberty and the towers of Manhattan in the distance, the promenade is a New York icon.

Ironically, the walkway was not planned as a tourist spot. It was a grand concession by New York City power broker Robert Moses to an organized and determined group of Heights activists who were not going to let Moses do to the Heights what he did to Carroll Gardens — destroy blocks of homes and divide the neighborhood with a sunken highway.

Geography Is Destiny

From the very beginning, the steep embankment on which the promenade perches has played an outsize role in the history of Brooklyn Heights. The bluff’s cooling summer breezes and magnificent view of the harbor and the growing city of New York led wealthy merchants and gentlemen farmers to claim the surrounding land as their own retreat and build country estates with orchards, fields and gardens.

By the time the Revolutionary War began, in 1776, a fortification called Fort Sterling existed at what is now the intersection of Columbia Heights and Clark Street. George Washington stood looking over the East River here, and quickly planned his retreat across, following the disastrous American defeat in the Battle of Brooklyn.

Curiously, Robert Moses was not first to propose a promenade here. When the street grid was being laid out and farms giving way to row houses and mansions in the early 19th century, a wealthy landowner who was instrumental in the development of Brooklyn Heights, Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, wanted to build a promenade — a walkway with gardens, for strolling about — on the cliff.

He wanted a private esplanade and gardens where the elite of the Heights could put on their finery and walk about and take in the views. There they could see and been seen. Some of his friends were horrified, so he dropped the idea, but to his dying day, he still advocated for his promenade.

A World of Elegance Above, the World of Commerce Below

In the 19th century, the streets of the Heights rang with the sound of construction as both speculative row houses and bespoke mansions were going up. Brooklyn Heights had seven houses in 1804. By the beginning of the Civil War in 1860, there were over 600. The gentleman farms and orchards were gone.

Abraham Lincoln took in the views on a trip to Brooklyn to visit Henry Ward Beecher’s church in 1864. He remarked that “There may be finer views than this in the world, but I don’t believe it.”

Henry Evelyn Pierrepont, Hezekiah Pierrepont’s second son and the most well-known member of the Pierrepont family, built his house on Columbia Heights, the rear of his grand palazzo overlooking the harbor, near the intersection of two streets that bear his name. He also built a retaining wall to fortify the Heights near his home. Pierrepont was soon joined by other wealthy families, such as the Lows, who all built large brownstone homes with gardens and verandahs facing the spectacular river view.

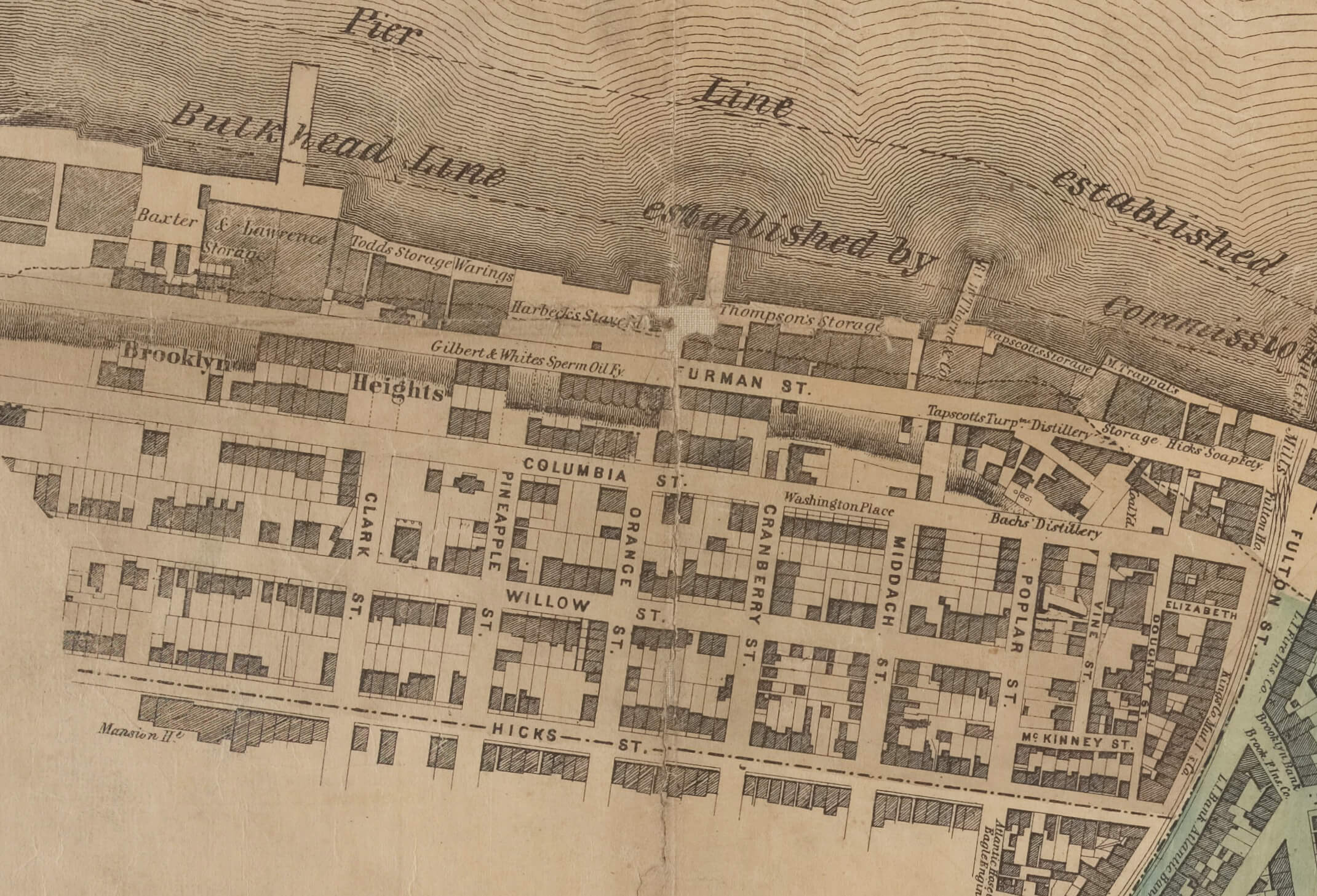

Below the bluff stood Furman Street, a busy roadway lined on both sides with “stores,” the name given to the three- and four-story brick warehouses that lined the Brooklyn side of the harbor between Red Hook and Wallabout. Many of the men in the mansions above owned the warehouses below. They had the inland warehouses constructed of brick vaults built back into the cliff.

This mode of architecture made it possible to both enlarge the stores deep into the land mass while supporting the bluffs and the houses above. This was augmented by Pierrepont’s retaining wall. Most of the homeowners laid out ornamental gardens and built greenhouses above the stores. Accessed by private stairs, these were the “lower gardens.”

Eventually, Montague Street ran all the way to Furman, with sidewalks and a streetcar running its length. By the late 1800s, Montague ended at a ferry terminal with boats to Wall Street.

By this time, Brooklyn Heights was completely built out. The early 20th century saw many of the oldest freestanding mansions go under the wrecking ball to make way for large luxury apartment buildings and residential hotels. As the 20th century progressed, more and more apartment buildings replaced the rows of townhouses. The neighborhood retained much of its wealth and standing for the same reason it always had: the pleasant breezes and views, the gracious architecture and, most important, the proximity to Manhattan.

Change Comes Like a Thundering Herd

“Master Builder” Robert Moses set his eyes on the Brooklyn waterfront during the middle of the Great Depression. No one before or since has wielded the kind of power Moses had over the building of New York City. He was parks commissioner, head of the Triboro Bridge Authority, and head of construction for the New York City Housing Authority — to name only three of his twelve career-wide titles.

Moses loved and believed in vehicular transportation and wanted to connect the entire city with a ring of multilane highways that crisscrossed the five boroughs. Nothing was more important to him than that — not neighborhoods, their architecture, their history or the people in them. They were all just impediments to progress that needed to be moved or removed. He preferred bridges over tunnels, highways over walkable streets, and automobiles over mass transit.

In the 1930s, with war on the horizon and millions of dollars of Depression WPA money still available, Moses convinced the federal government that building a highway connecting Brooklyn to Queens was necessary to the national defense. With that money he proposed an expressway — a divided highway that could transport troops and military equipment, if necessary, as well as trucks and cars.

Using part of the superstructure of the defunct Third Avenue El, the highway would come up from Bay Ridge, travel through Sunset Park and Gowanus, cut through Red Hook/Carroll Gardens, bisect Brooklyn Heights, turn into Wallabout, continue on through Greenpoint and out into Queens.

Construction kicked off in 1939, with work starting on the northern and southern ends of the highway first. The Heights section was one of the last to be built. Moses cut a trench along Hicks Street in Carroll Gardens, dividing that working-class neighborhood in two. The factory and dock workers and their families in the Carroll Gardens and Red Hook neighborhoods had no political power and no real voice. The highway cut through their neighborhood like a hot knife through butter.

But Brooklyn Heights was different. There was still a lot of money and political clout there, especially in the families whose properties were closest to the bluffs. On September 19, 1942, the Brooklyn Eagle’s headline read “Plan for the Express Highway Is Shocking.” The story revealed that one of the proposals being considered would create a curved diagonal highway that would cut through the Heights from Atlantic and Hicks, curve near Pierrepont and then join the rest of the BQE at Tillary and Washington streets. The new Appellate Court building on Monroe Place, which was less than five years old, would have to go.

An alternative plan proposed that the new expressway’s route would hug the shoreline and run along industrial Furman Street. The news galvanized Brooklyn Heights, especially members of the Brooklyn Heights Association. This group, founded at the beginning of the century, was comprised of some of the Heights’ wealthiest and most influential residents. The Association’s president, Roy Richardson, was a Wall Street corporate lawyer. Another vocal member was Fred Nitardy, a vice president at nearby pharmaceutical company Squibb.

The association came out hard and fast against the proposal to bisect the neighborhood at a City Planning Commission hearing in 1943. That plan had been championed by Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore, who wanted upgrades to a new Brooklyn Borough Plaza. Moses had already decided that cutting though the Heights was too expensive and difficult, and had his staff planners, along with engineering firm Andrews & Clark draw up plans for a multilevel highway with two levels running next to Furman Street. Originally, the upper level of the highway would have been where the promenade is today.

Nitardy’s house was on Columbia Heights. His backyard faced out over the bluff. He and his wife had an extensive private garden built both on land and down on the warehouse roofs. During the Planning Commission’s meeting, he tried to cut a deal with Moses on the divided highway. If Moses made the highway a three-level covered highway, dug into the embankment of the Heights, then he and the other homeowners on Columbia Heights would give the city the right of way to their property, provided the city allowed them to rebuild their private gardens on top of it.

Moses is reported to have liked that idea, but said he wanted the gardens to be a public promenade, not just enjoyed by a few private homeowners. In May of 1943, the City Planning Commission approved the covered highway. Cashmore send Nitardy a letter informing him that the covered highway deck behind his house would become a public esplanade. Longtime Heights people say Nitardy and his wife never got over the loss of their gardens or their privacy.

A Cantilevered Highway Is Born

Demolition of the warehouses on the landward side of Furman Street began in the fall of 1946. Photographs show the vaulted chambers of the warehouses holding up the Heights — something most people had no idea existed. Although most of the Heights was saved, there were casualties. The Riverside Apartments at the Atlantic Avenue end of the Heights lost a wing and some grounds for highway ramps.

The grand Italianate palazzo of Henry Pierrepont at 1 Pierrepont Place was torn down. A playground stands there now. At the northern edge of the Heights, parts of Hicks, Poplar and other small streets were torn away for the highway, including the house from which John Roebling watched the Brooklyn Bridge rise, and 7 Middagh Street, which in the early 1940s was home to writer Carson McCullers, who opened her home to W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten, Gypsy Rose Lee, Kurt Weill and others.

Meanwhile, under the Heights, the cantilevered highway was built up over the course of several years, a process that drove those who lived near it insane. Quite understandably they complained of years of pile pounding, construction noise, dust and vibrations. The highway was not opened to traffic until 1954. In the meantime, the southern half of the promenade opened in 1950, with the northern portion opening a year later.

Most of the homeowners lost some of their rear yards, although the promenade itself extends from what were once these home’s “lower gardens,” formerly on the warehouse roofs. Between the Columbia Heights backyard fences and the paved promenade walkway is a wide strip of green maintained by the Parks Department. Technically, the promenade is not a park, but under the Department of Transportation’s authority.

The view that we all know and love today was not the view people saw in 1950. The port side of Furman Street remained warehouses controlled by the Port Authority. Some of those warehouses were high enough to obstruct full views of the harbor. In 1953, the Port Authority announced they wanted to build warehouses that were even taller. The public was outraged and demanded the views remain. The Port Authority objected, and Robert Moses wrote that the city should not spot zone an area just for a view. The city disagreed, and placed height restrictions on new warehouses. In 1974, the city went further and created a Special Scenic District that prevented construction obstructing the view. It remains in effect today.

Photos from the 1950s show ships in the piers and the warehouses next to them. They would soon be gone. Shipping ended in Brooklyn as the container ships moved to larger, deeper and newer docks in New Jersey. By the end of the 1950s, the tall warehouses had all been torn down. Over the last 10 years, those piers and docks have become Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Today, although condos have risen where warehouses once stood, and the BQE under the promenade urgently needs repair, tourists and locals alike enjoy one of the greatest views in the entire city. The promenade is home to joggers and cyclists, strollers, couples and families. The life of the city takes place on the benches and pathways. The homeowners of Columbia Heights may not have the privacy and private gardens that their predecessors enjoyed, but they still have that amazing view, something that people are willing to pay large amounts of money for.

But whether rich or poor, local or tourist, the promenade is open to all. In a much more egalitarian way, it’s the place old Hezekiah Pierrepont wanted — a wide scenic pathway, with gardens and greenery, some benches to rest on, where one could see and be seen — high above the river, taking in that view.

Editor’s note: This story originally ran in the Fall/Holiday 2018/19 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- The Promenade Should Stay, Locals Agree. But What Should Be Done With the BQE?

- Take a Stroll on the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, Circa 1971 (Photos)

- Hated, Beloved and Highly Used: The Past, Present and Future of the Brooklyn-Transforming BQE

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment