Walkabout: A Klavern in Brooklyn

It was a frigid night on January 26th of 1923, in Brooklyn. The holidays were over, a new year had begun, a cold dry year, as the third year of Prohibition was getting underway. Eight young men were piled in a car, travelling down Clermont Avenue, near Dekalb, in Fort Greene. They were loud, loud…

It was a frigid night on January 26th of 1923, in Brooklyn. The holidays were over, a new year had begun, a cold dry year, as the third year of Prohibition was getting underway. Eight young men were piled in a car, travelling down Clermont Avenue, near Dekalb, in Fort Greene. They were loud, loud enough that they caught the attention of Detective James Reilly, of the bomb squad, who was standing on Clermont Avenue. He also noticed as they came closer that the car did not have its lights on, so he stepped out and stopped the car, ordering them to pull over. The eight young men, John Collins of 28 Herkimer Street, Ellsworth Norse of 311 East 18th Street, Alfred Clark of 2104 Caton Avenue, Robert Fisher of 135 Quincy Street, William Simmons of 218 Sullivan Street, Charles Mulford of 58 Hawthorne Street, Thomas Jones of 363 Grand Avenue and John Gilmour of 71 New York Avenue, were all charged with disorderly conduct. Collins was further charged with possessing a blackjack and Fisher with possessing a bottle of whiskey, a violation of the Prohibition Act. Where had these young swells been that they were in such a loud and celebratory mood? According to later investigation – they were at a Ku Klux Klan meeting, at 182 Clermont Avenue.

In addition to the bottle of whiskey and the blackjack, the police also found a white robe and hood; the robe had a purple cord, and an attached cape with red lining and the insignia “KL” in yellow, red and purple. The hood had eye holes cut out of it. All eight men were arrested and tossed in the Raymond St. Jail overnight, and were arraigned the next day at the Gates Avenue Courthouse, on Gates near Marcy Avenue. The whole bomb squad was now on the case, as Det. Reilly had called his supervisor, Lt. James Gegan, who was actually listed as the arresting officer of record. The District Attorney had to be called to find out what kind of charges to file, lawyers for the defendants had to be notified and parents called. This case would attract the media. The Klan was in town, and these young men had been to a “klavocation.”

A general history of the KKK should be given, but most people know the basics. The organization was founded in the South after the Civil War, during Reconstruction, by ex-Confederate soldiers, as a white supremacist group, to keep newly freed blacks in their places, and also to run the white Northern “carpetbaggers” out of the South. They died out in the 1870s, but were resurrected in the early 1920s, inspired by the success of D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation,” where much of the symbolism and the wardrobe originates. They then spread across much of the country. This time, they preached a jingoistic Americanism, and in addition to being racist against blacks, they were also highly anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic and anti-communist.

They never really had a stronghold in New York City, a city of immigrants, filled with different nationalities and ethnicities and unions. But their message of white supremacy did resonate with many who saw not only black and other minorities working in many parts of the general society, but worse, Jews, Catholics and unionists taking over New York. Catholic and Irish Al Smith, the governor of New York, was one of their biggest targets.

An investigation of the Klan had been going on in Yonkers, where a Klavern had sprung up. The Manhattan District Attorney’s office had a man undercover there, who revealed the leadership and also the organization of the secret society. According to the New York Times, in February of 1923, it cost $10 to join the Klan, and an initiate would get a special button to wear and learn the password and countersigns. Apparently, it took 20 minutes to get past all the secret passwords, signs, countersigns, handshakes and nonsense before being admitted into a meeting. The meetings usually took place under different organizational names.

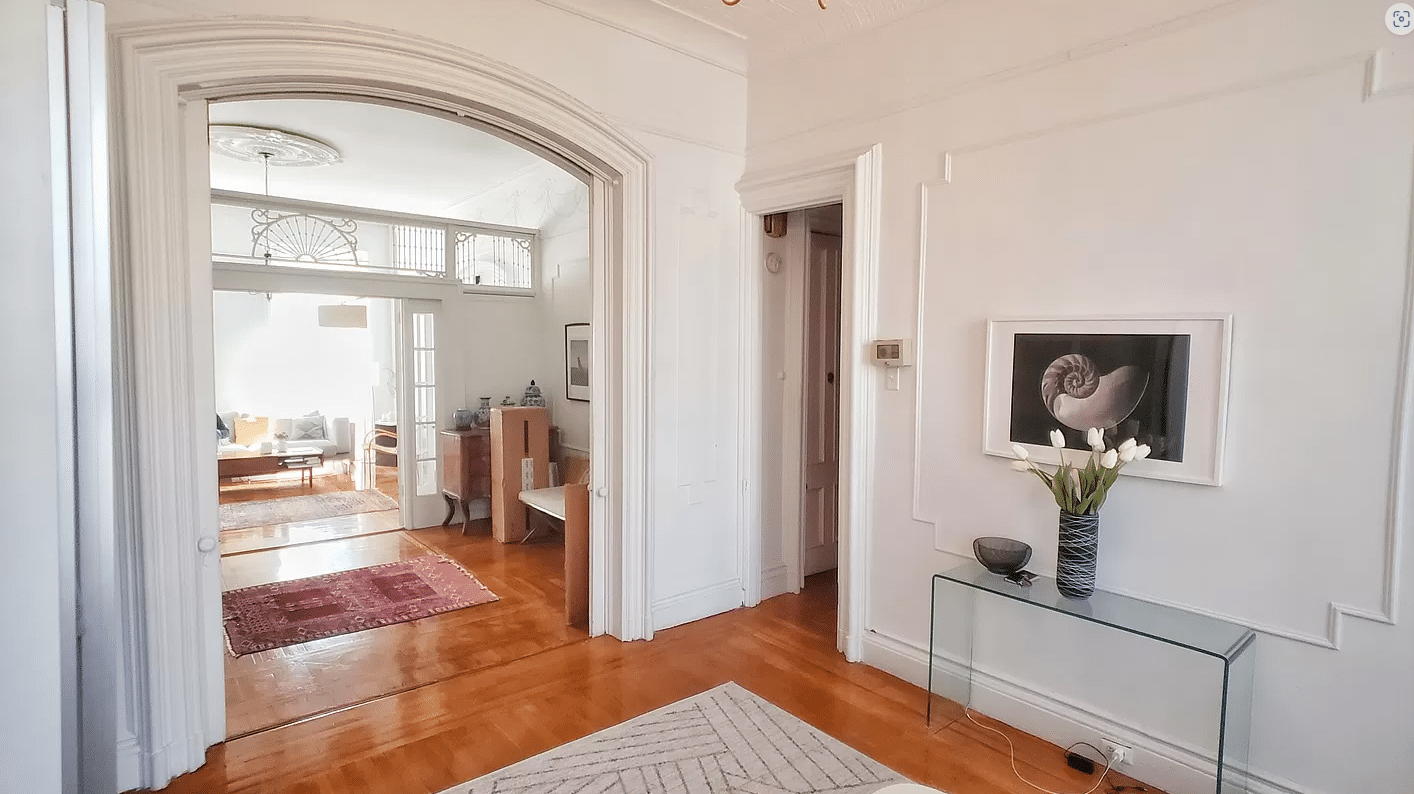

You couldn’t just announce you were having a Ku Klux Klan meeting, after all. Meetings were held under names like the Owl Club, the American Society, the Turtle Club and the National Civic Association. Back in Brooklyn, it was much the same. The owner of 182 Clermont, a former church now called the Ace Square Club, where the Klan meeting was held, had been told that they were renting their space, on the second and fourth Thursday of each month, to a group called the “Circle Club.” Unknown to them, the “circle” was made up of Klansmen recruiting from Brooklyn’s young and bored. Ironically, traffic court was also held in the same building during the day, and no one knew what the Circle Club was.

When the Clermont Eight were brought before Magistrate H. H. Dale the next day, he was not happy. He fixed bail for all of them at $1,500 and attached another $1,000 to the bails of blackjack-toting Collins and whiskey-toting Fisher. Nineteen-year-old Mr. Fisher, a Pratt Institute student, denied that the bottle was his, and also said that he was just getting a ride, and had no idea that the rest of the guys had just come from a Klan meeting. All of the men, except Mulford and Collins, were represented by an attorney named Malcolm Ross Matheson. He insisted that the boys had been mistreated in the jail because they had missed a meal, and were being persecuted for youthful hijinks.

But an extremely angry Magistrate Dale was quoted in the Times with the following statement: “I am talking for myself as a citizen when I say that Brooklyn has no room for the Ku Klux Klan, or persons who believe in it, or those who intend to become interested in such an organization. My advice to all persons who are thinking of becoming affiliated with the Klan, is to get out of Brooklyn.”

Magistrate Dale went on to question the defendants, but wasn’t getting any answers. He asked their lawyer where the young men were going that night, with masks and robes and blackjacks? Didn’t Brooklyn have enough criminals out on the street already? The lawyer replied that these young men were not the type to carry blackjacks. The judge then asked, “Were they going to a masked ball, or what?” The police reported that the blackjack-wielding defendant, John Collins, a dance teacher by day, was the owner of the robe and hood found in the car, and was a leader of the Klavern. He would make bail later that day, and be released. Most of the others made bail as well. John Gilmour’s parents, John Sr., and Emily, came to the courthouse to bail out their son. “If I had my way, I’d let him stay in jail,” John Gilmour said to the Times. “I am not in sympathy with the Klan.” His wife put up another property she owned as collateral, and the Gilmours took their son home. They tried to bail out Pratt student Fisher, but they didn’t have enough money.

The police announced that they had found papers listing the members and leaders of the Klavern, and would be acting accordingly to root them out. The District Attorney of Kings County, Charles Dodd, was quoted as saying, “No organization or group of persons can trifle with the law in Brooklyn and get away with it.” You can almost hear the music swelling in the background. The fate of the eight young men from Brooklyn remains unknown. Most likely, they paid a stiff fine for disorderly conduct and were forgotten. It probably scared them straight for life. John Collins was probably investigated some more, and for all we know, he was tossed out of the Klan for blowing their cover.

I found this story when I was researching the home of John Gilmour, which is a freestanding brick mansion in Crown Heights North. The Gilmours were about the third or fourth owners of the house. By the 1970s, the house ended up a burned-out shell, abandoned for over thirty years. It was rehabbed into a three-family house in 2006, and is again a proud part of the community. What those walls must have heard when John Gilmour got his wayward son home that day in 1923. (This story first appeared on December 21, 2010)

(Photograph of the Klan making a charitable stop at an orphanage: Wikipedia)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment