Walkabout: The German American Stores Fire, Red Hook

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris) Today we walk along the piers in Red Hook and admire the view of the harbor and the Statue of Liberty. We enjoy the quietness and relative remoteness of the surroundings. You can hear the seagulls, the gentle slap of the water against the rocks, and the excited laughter…

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

Today we walk along the piers in Red Hook and admire the view of the harbor and the Statue of Liberty. We enjoy the quietness and relative remoteness of the surroundings. You can hear the seagulls, the gentle slap of the water against the rocks, and the excited laughter of children. If you turn around and look towards shore, the iconic warehouses called “stores” await you; today enviable apartments, lofts and working spaces. Red Hook is a unique place.

But back in the 1800s, the scene would be very different. There would be no strolling along the piers, as this was the site of one of the busiest ports in America. Goods from all over the world arrived and departed from here. The stores that remain were joined by dozens of others along the shore. Granaries rose along the waterfront, joining sugar refineries, factories and warehouses making and storing more goods and products that you could imagine.

The Red Hook waterfront was a rough place. Men from all over the world mixed here, jostling each other as they rolled wagons and barrels of merchandise to and from the ships and the stores. These stores held everything from jute to tobacco, leather hides, coffee, cotton, molasses and sugar. They also stored pitch, resin, turpentine and benzene.

Today, our laws prohibit the kind of proximity that was par for the course back then. And it wasn’t just on the piers that you might find a mixture of flammable materials next door to known accelerants. The nearby factories of South Brooklyn and Brooklyn Heights were the same, with a mixture of industries together that just begged for fires and explosive disasters. Paint factories on the floor above a paper plant; a turpentine factory next door to a lumber yard.

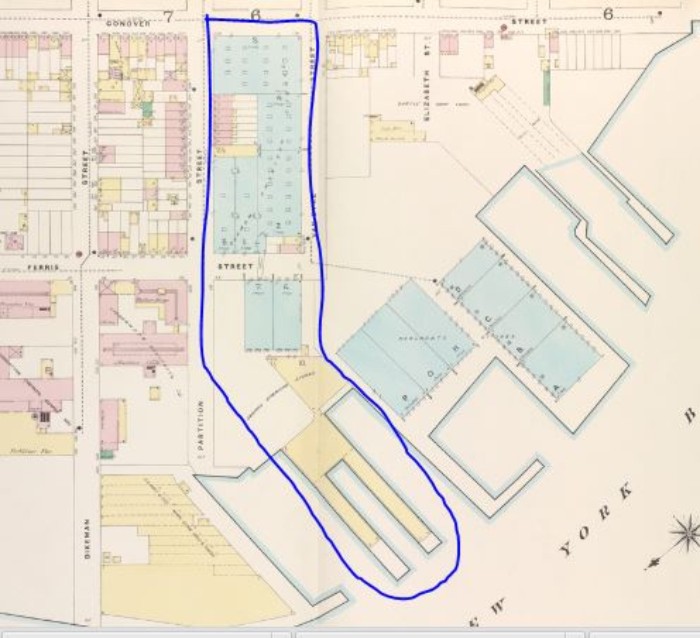

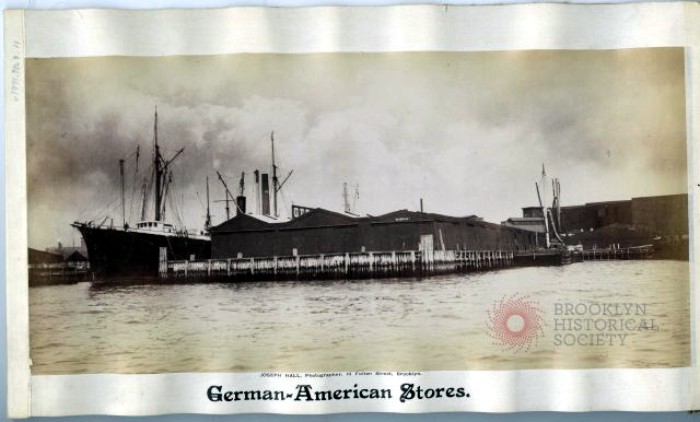

One of the larger stores in the Red Hook piers was the German American Stores. Its only remaining warehouse building is at 106 Ferris Street, between Coffey and Van Dyke Streets. Today, the Louis J. Valentino Park is just north of the warehouse, but back in the mid and late 19th century, the German American Stores buildings reached to the shoreline, and extended out to the edge of their long pier.

The German American Mutual Warehousing and Security Company was big. This remaining building is said to date back to the mid-1860s and was built specifically to hold cotton. Brooklyn was the staging area of most of the cotton that came from southern plantations, on its way up to mills in upstate NY and New England.

A lessee of the warehouse was a company called Bartlett & Greene. In 1875, the Brooklyn Eagle announced that they had 35,000 bales of cotton stored here and in another company’s Red Hook stores. Bartlett & Green also dealt in sugar, and stored tons of it in the German American warehouses.

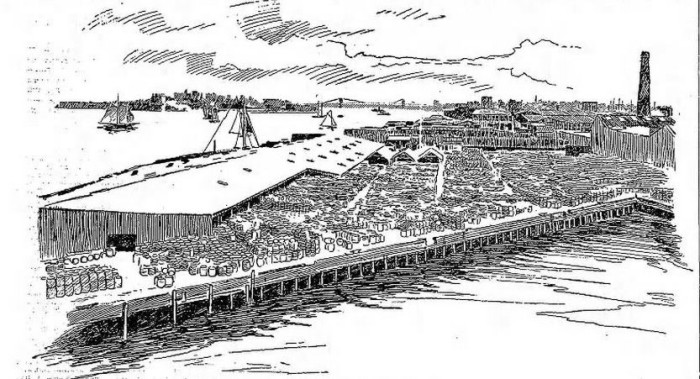

In the same year, the paper announced that the German American Stores was going to expand, building more warehouses, and expanding out onto the pier. By 1886, as seen in the insurance map, they had made major expansions, and had enclosed and dock space for tons of goods.

By the 1890s, the German American Stores were one of the largest recipients of cotton on the waterfront. The Brooklyn Eagle Almanac stated that they had 4,000,000 square feet of storage. They also had 400 feet of water frontage.

On October 24, 1898, a British barque called the Andorinha was docked at Pier 39, the German American Stores’ dock. The Andorinha was a handsome, four-masted clipper ship, with a steel hull. She was 346 feet long and 25 feet deep, weighing in at 3,440 gross tons.

She was out of Liverpool, captained by David Morgan, and was coming into port from Calcutta, India. She had arrived on October 2nd, with her hold bulging with almost 25,000 bales of jute.

They also had on board 50 bales of burlap, a quantity of shellac, a load of raw silk, and 1,500 tons of saltpeter. Saltpeter is potassium nitrate, a major ingredient in fertilizer and the oxidizing agent in gunpowder.

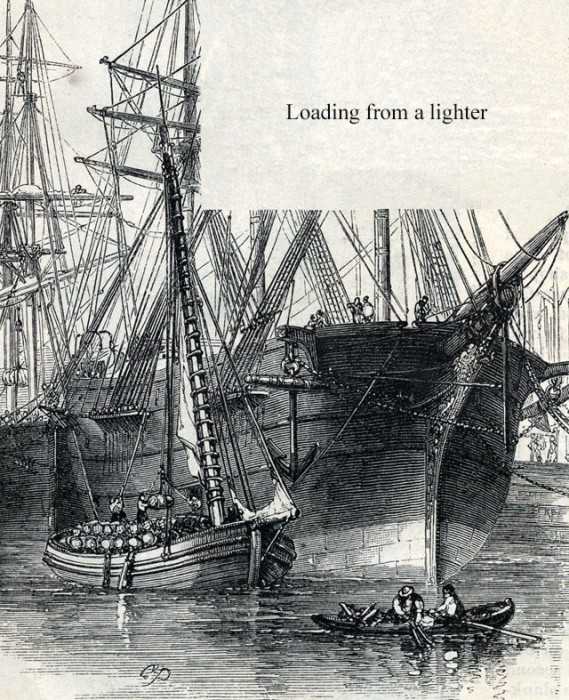

The stevedores and the crew of the Andorinha had been unloading the ship for the last two weeks. They were being aided by two smaller boats called lighters. The William M. Brown and the Walter P. Klotz were still moored next to the larger ship.

2,500 bales of jute were piled up on the pier, along with 200 bales of cotton from another ship. The pier itself was brand new, and the workmen who had built it were still on site, putting the finishing touches on it.

Later allegations as to where the fire started flew back and forth, but the preponderance of evidence showed that it began on the Andorinha. It may have started from a spark from a sailor smoking his pipe, or just an accident of two metal objects hitting each other.

Where ever it came from, around 3:15 in the afternoon, a spark set the jute on the Andorinha on fire. Jute is, after all, dried plant fibers. It went up in an instant, spreading from bale to bale before anyone could stop it.

The fire jumped from the ship onto the pier, and lit the jute and cotton bales up as if they had been soaked in gasoline. In ten minutes the fire had gone to four alarms.

The pier and its contents were burning, the Andorinha was burning, and the fire quickly jumped onto both lighters, moored next to the ship and the pier. They were now burning, each with 600 bales of jute on board.

Pier 38 was the next pier over from German American. It was owned by the Atlantic Dock Company, and had been leased to the G.L. Hammond Company. The fire jumped and set Pier 38 on fire, totally destroying it.

Fifty of the German American Company’s longshoremen had started a bucket brigade when the fire first appeared, but the fire spread too hot and too fast. As the heat rose on the burning pier, they had to abandon their efforts and run for their lives.

Over on the burning Andorinha, the captain and his men, after failing to put the fire out, had jumped overboard to escape the flames. When the fire department arrived, minutes after the alarms had been sounded, they realized they had a hell on earth facing them.

The flames from the burning jute and cotton could spread across the Red Hook piers, and spread to the factories and homes further inland. Even more frightening, the ton of saltpeter in the hold of the Andorinha had not been offloaded yet. It could explode at any moment, sending the fire out into Brooklyn.

To make matters worse, the fire was now spreading to Pier 40. Moored to her was a ship out of South Carolina called the Wacamaw. She was carrying a cargo of turpentine, resin, and benzene. The pier was home to the Union Naval Stores. It was a huge pier, larger than most, much of which was covered by open storage sheds running the length of the pier, covered by a roof.

Under that roof sat thousands of gallons more of the same turpentine, resin and benzene. As the hot sparks flew across the pier, they began to lick playfully at the barrels on the pier and at the Wacamore. This was going to get much, much worse.

Read Part 2 of this story here.

Above illustration: German American Stores, 1898. Brooklyn Eagle.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment