An Inside Look at Saving Place: 50 Years of New York City Landmarks

“Saving Place: 50 Years of New York City Landmarks” just opened at the Museum of the City of New York. We talked with curator Donald Albrecht about the exhibition, a celebration of the 1965 Landmarks Preservation Law and its impact on the city. “New York has always been a city of great change,” says Albrecht, “and part of our…

“Saving Place: 50 Years of New York City Landmarks” just opened at the Museum of the City of New York. We talked with curator Donald Albrecht about the exhibition, a celebration of the 1965 Landmarks Preservation Law and its impact on the city.

“New York has always been a city of great change,” says Albrecht, “and part of our architectural legacy has been figuring out how to manage that perpetual change.”

Carnegie Hall, 1895 | Byron Company Collection

Carnegie Hall, 1895 | Byron Company Collection

“Everyone thinks it started with the destruction of Penn Station in the 60s and then the law was passed,” Albrecht says, “but it actually goes back to the 19th century. 1965 is when city government got involved, but there’s civic groups, individuals, historians, photographers, the press… all involved in different ways, and we wanted to show how the different forces come together.”

![Untitled [The demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-1965.]](http://www.brownstoner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/museum-of-the-city-of-new-york-demolition-of-pennsylvania-station.jpg) Demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-65 | Gift of Aaron Rose

Demolition of Pennsylvania Station, 1964-65 | Gift of Aaron Rose

There are four types of landmarks: individual buildings, historic districts, interior landmarks, and scenic landscapes. Of the four, interior status is the trickiest. The Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building has it, as does the inside of Grand Central: “this gets into issues of how it can be used, and that’s when money really gets involved.”

“A building must pass the 30-year mark before it can be listed, it’s importance needs to be determined, and then any change to it must be approved by the commission,” says Albrecht. “The word that’s used, a very interesting word, is ‘appropriate,’ and it’s meant to be a very flexible term. Because what’s appropriate evolves with the commissioners, the architects, the changing ideas of suitability.”

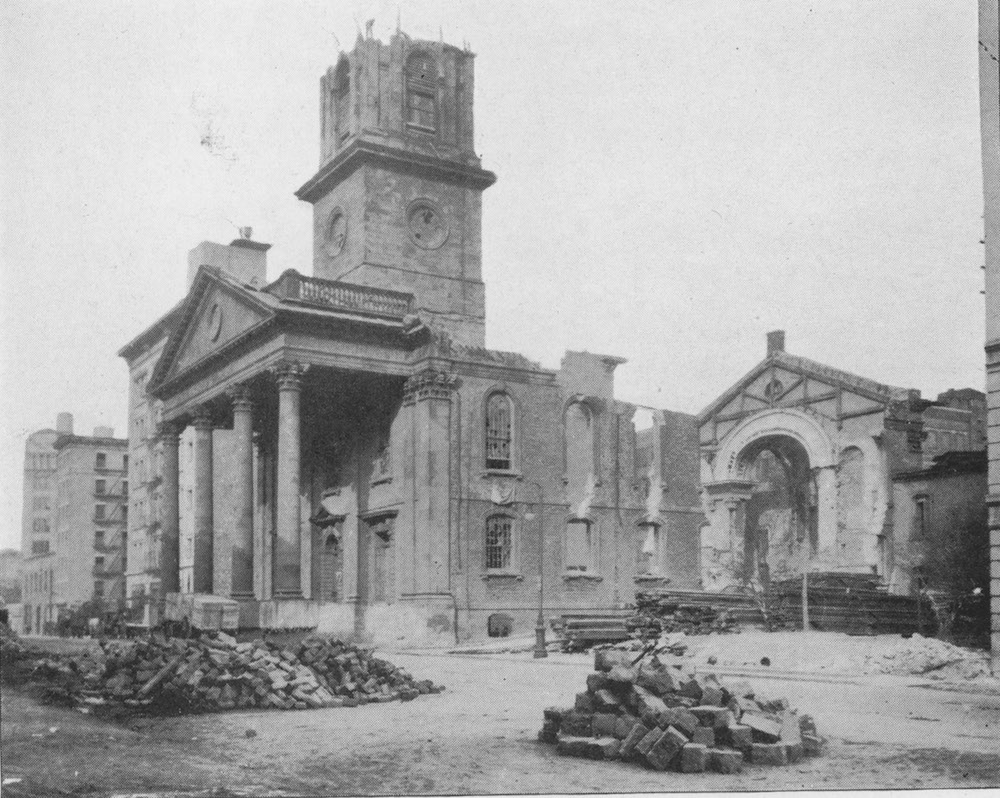

St. John’s Chapel being demolished, 1918 | American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society/Metropolitan History

St. John’s Chapel being demolished, 1918 | American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society/Metropolitan History

Along with the original Penn Station, a number of significant buildings have been lost, either before the passage of the law or due to a lack of designated status. The original Ziegfeld Theater and Metropolitan Opera House were both torn down. Carnegie Hall and Grand Central Station narrowly escaped. Recently, MoMA purchased the Folk Art Museum and the land beneath it and demolished it.

On the other hand, there are some buildings where there is little question as to their historic importance. The Seagram Building by Mies van der Rohe, for example, is widely considered to be a modernist masterpiece, and as such was designated as a landmark within three months of turning thirty.

![[131 and 135 Hicks Street.]](http://www.brownstoner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/museum-of-the-city-of-new-york-131-135-hicks-street-1940.jpg) 131 and 135 Hicks Street, Brooklyn Heights, 1940 | Photo archives

131 and 135 Hicks Street, Brooklyn Heights, 1940 | Photo archives

Alongside the museum’s treasure trove of historic New York photographs, commissioned work by Dutch photographer Iwan Baan shows what New York looks like today.

“He spent two weeks, not photographing the landmark alone, but in context with people,” says Albrecht, “showing how landmarks are a dynamic mix of old and new, and how that characterizes urbanism in New York.”

New York Post Office, 1902 | Gift of Anthony C. Wood

New York Post Office, 1902 | Gift of Anthony C. Wood

In the 1978 battle for Grand Central, the Supreme Court determined that a city has the constitutional right to protect its landmarks. Today, 4% of the city — or 27% of Manhattan — has designated landmark status. The city’s Landmark Commission is the largest of its kind in the country, and has inspired similar bodies in other cities.

Through a combination of photographs, architectural models, and text, the exhibition captures what the city has gained, what it has lost, and the constantly evolving effects of this historic law.

“Saving Place: 50 Years of New York City Landmarks” runs from April 21 to September 13 at the Museum of the City of New York. Click here for visitors hours, directions, or to buy tickets to the exhibition.

Comments