Walkabout: Plastered, Part One

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story. When it comes to real estate in a city like ours, with housing that spans the space of a few hundred years, there are two types of people in the world: old house lovers and new house lovers. The reasons we like what we…

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

When it comes to real estate in a city like ours, with housing that spans the space of a few hundred years, there are two types of people in the world: old house lovers and new house lovers. The reasons we like what we like are myriad and often complicated, but if one can afford to have a choice in what kind of building they live in, just about everyone has a preference.

A house or apartment is made up of many components, many of which are cosmetic, but one thing that is not is framing. Whether new or old, where we live is made up of walls, ceilings and floors. Two of those components beg the question – plaster or drywall?

I have never lived in a new house. I grew up in a 200-year-old vernacular Italianate farmhouse upstate. When I went to college, I lived my first year in a dorm from the 1890s, followed by three years in another built in the 1930s, designed to look like a medieval college in England. When I moved to New York City, I lived in an Art Deco apartment building in the Bronx, followed by almost 30 years in two different Brooklyn row houses. One was from the late 1870s, the other from 1899. I write this article from a Troy row house from that same year. All of these places had one thing in common – nice thick old plaster walls.

Plaster is old stuff. Ancient man covered twigs and reeds with layers of mud, and let it harden in the sun, creating shelters that offered more protection from the elements and vermin than simple sticks or branches. That was the beginning. The ancient Egyptians discovered the formula for calcined gypsum that is identical to today’s plaster of Paris. They used it in tombs 4,000 years ago, and we can still see intact examples today. The Greeks and Romans used plaster to make stucco, for both interior and exterior use.

Plaster, or some kind of hardened, smoothed surface material, has covered the interior walls and ceilings of our buildings ever since. It has also been used on the exterior to stucco buildings, half-timbered walls, and other surfaces, depending on country, tradition and climate. Today, we generally call exterior coverings “stucco” and interior “plaster,” but the formulas are similar, as are the methods and steps in applying them.

Since many cultures have a long history of plasterwork, and there are many names, methods and traditions, both practical and artistic, for clarity’s sake, in this article, I’m talking about North American plaster walls and ceilings. The great thing about plaster is that it can be applied over anything. That’s why you’ll see plaster walls with brick or stone directly behind them. Sometimes you’ll see lath. Sometimes there will be a more complicated framework of wood or metal, especially if the plaster wall or ceiling has a special shape or feature.

The stuff we generally call plaster is plaster of Paris, or gypsum. It gets its name from the large gypsum deposits originally found near Montmartre, in Paris, centuries ago. The gypsum is heated until it becomes a powder. When that powder is mixed with water, it becomes plaster. The chemical reaction of water and gypsum produces heat, and as the water evaporates, the gypsum hardens into whatever shape it has been put into. As you no doubt know, plaster can be forced into molds for decorative objects, can be used in conjunction with strips of cloth to create artwork and medical casts, and all kinds of other uses. Plaster of Paris is everywhere, from kindergarten art rooms, to our greatest museums, and the halls in those museums, and everywhere in between.

Up until the end of the 19th century, and beginning of the 20th, the walls of the old houses we live in here in New York were constructed of a different kind of plaster called lime plaster. It is made of powdered lime, called quicklime, procured from heated and powdered oyster shells and limestone. The other ingredients are an aggregate like sand; a fiber such as horse or animal hair, and water. Most of our brownstones, especially the earlier ones, had lime plaster walls and ceilings. Around 1900, advances in gypsum refining made that mineral a preferred substance, and gypsum once again made a plaster comeback. The building trades liked gypsum better anyway, because it had a much shorter drying and curing period.

No matter if the plaster was lime or gypsum, the methodology of plastering was the same. Your basic plaster wall had three coats of lime or gypsum plaster. The first coat is called the scratch coat. It is the roughest coat of plaster, the one that is applied directly to the brick or stone wall or lath. In our row houses, the exterior walls of brick had the scratch coat applied directly to the brick. If you’ve ever exposed brick yourself, you’ve seen that the bond between the brick, mortar and plaster can be difficult to be broken, even 100-plus years later. The water in the plaster was absorbed by the porous brick, pulling the plaster into the brick’s surface, creating suction, and a tight and lasting bond.

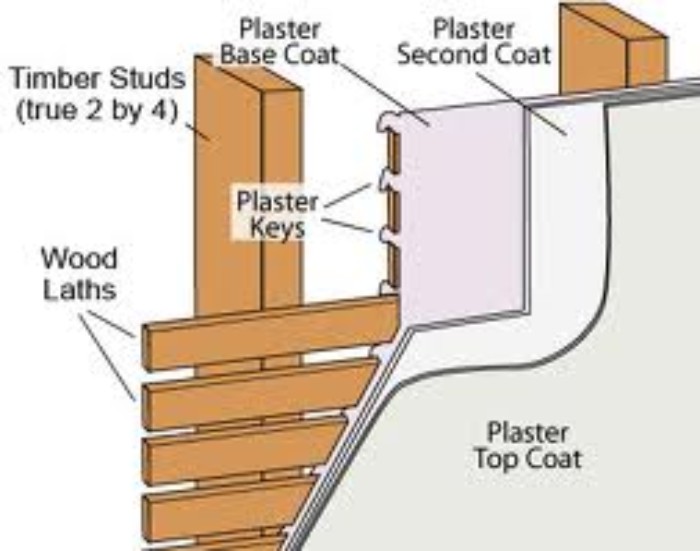

The interior partition walls and the ceilings were made of wood framing and lath. True 2x4s were nailed to form wall and ceiling studs. One quarter inch rough wooded lath strips, of about two inches wide and four feet long were nailed across the studs, with a 3/8-inch gap between the boards. The scratch coat was applied to the lath, and forced into the spaces between the boards. It was applied hard enough so that plaster dripped down behind the lath, creating plaster “keys.” The keys are what hold the plaster onto the lath.

The scratch coat is a rough coat with aggregate and fiber. Anyone who has worked with old plaster has seen horsehair or other animal or fiber hairs mixed in the first two coats of plaster. The sand and the fibers hold this coat together, and form a very good base for the other two coats. The scratch coat was generally about 3/8 to a half inch thick. The plasterer would allow this first coat to dry completely before putting on the next coat. That could take several days.

The second coat or the brown coat was next. It also had horsehair or other fibers, but had more sand mixed into it. It was troweled on over the scratch coat and built up to another 3/8 of an inch in thickness. Again, the water in the brown coat was absorbed by the scratch coat, and the suction made both layers firm and secure. This coat was then allowed to completely dry. The last coat was the finish coat, or skim coat. This layer had much less sand, no fibers, and was a thin, ¼-inch coat of fine plaster.

A master plasterer could make this skim coat as even and plumb as can be, and smooth as the proverbial baby’s bottom. He could also create curves, as found in vaulted ceilings or ceilings where the right angle created by the wall and ceiling joining was curved into a gentle convex curve, blurring the line between wall and ceiling. After he was done, the entire walls and ceilings were allowed to dry, and the surface was allowed to cure. At the end of that period, the walls and ceilings could then be papered or painted.

As the 20th century dawned, interior design trends changed. Swirled and patterned plaster finishes became popular. Fine sand was added to the finish coat, and before the plaster had completely set, the surface was swept with a broom to bring up the sand. Swirl or wave patterns could be made permanent. These were popular both on walls and ceilings. For a different effect, marble dust could be added to the topcoat, and burnished with a trowel to create the finish we now call Venetian plaster.

As mentioned earlier, gypsum plaster replaced lime plaster around 1900. Lime was great stuff, but it had its limitations. It could be rendered inert and useless by premature exposure to water, or carbon dioxide. For builders though, the big one was that it took forever to cure. A year was the recommended time period before painting or wallpapering the surface. Developers were not happy about waiting that long. They worked around it as much as possible, and added plaster of Paris in small amounts to hasten curing, but when 100 percent gypsum made a return, they were thrilled. It took much less time to set, and cured in a matter of weeks. Now we’re talking.

In 1909, the huge Chicago-based United States Gypsum Company bought out a smaller company called the Sackett Plaster Board Company. They had invented a process of sandwiching layers of gypsum between sheets of paper. By 1916, US Gypsum was marketing a variation of this process as “pyrobar,” which had a layer of gypsum between two pieces of fireproof materials, made into tiles. They thought pyrobar would revolutionize the building industry. The reaction was “meh,” so they went back to playing with the concept of “Sackett board,” as these sandwiched plaster boards were called.

They finally came up with a board that had only one layer of gypsum in the center, surrounded by two sheets of paper product. US Gypsum decided to call their new sandwiched gypsum board “Sheetrock.” By now it was the late teens, early 1920’s. The public took one look at sheetrock and once again, said “meh.” How could a quickie, mass-produced thin plaster sheet like that ever take the place of time-honored, solid plaster walls and ceilings? What an absurd idea.

Next time: Sheetrock takes on plaster. The story continues.

(Lath and keys: photo from Wikipedia)

“I have never lived in a new house.”

New reality series: MM Lives Modern

MM lives in modern / contemporary homes for a week. Will she survive?

1st episode, MM lives in Mies’ Farnsworth House.

plaster done right is really nice..

Oooo, where?