What Was the Turkish Corner?

In the late 19th century, globally influenced design trends found expression in a short-lived fad known as the Turkish corner.

An illustration of a “nook of solid comfort” in a 1908 wallpaper catalog. Image from Home Decoration by Alfred Peats Prize Wallpapers via HathiTrust

In the latter part of the 19th century, when ladies and gentlemen of the upper classes visited friends and social acquaintances, they might be introduced to a special parlor room or corner of a room that was resplendent with a multitude of throw pillows, overlapping carpets, lanterns, and other furniture and accoutrements from the then exotic-seeming lands of the Near East. Today, we might think of these as “Bohemian style,” which happens to be quite popular now, but the Victorians called those spaces “Turkish rooms” and “Turkish corners.” Anyone who was up on the latest interior fashions had one.

The fascination for all things Middle Eastern was part of a larger art and design philosophy known as the Aesthetic Movement. It began with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of the 1850s, grew to encompass William Morris and fellow designers and artists, evolved into the British Arts and Crafts movement, and ended with Art Nouveau in the first decades of the 20th century. The Aesthetic Movement began in Great Britain, but soon spread to other parts of Europe and — most important to our tale — to the United States.

The Aesthetic Movement was, in part, a reaction to the ascendency of the Industrial Age, which dominated both Britain and the U.S. New advances in manufacturing technology and materials meant that factories could produce all sorts of consumer goods that were snapped up by a growing population of middle and upper middle class people. The time-tested art of the craftsman was traded for products made by an underpaid factory worker in a city. It was the beginning of the “more is more” era.

Meanwhile, thanks to European imperialism, the world was growing smaller. England was conquering and establishing colonial rule in Africa, India, and the Far East, while France, Germany, and other countries were making colonies out of nations in the Middle East, North Africa, and the rest of the African continent. It didn’t take long before the arts and cultural features of these regions made their way into Western society as imported goods and new ideas.

Japanese art and design; Indian textiles and crafts; Chinese silks and porcelains; patterns, colors, and furnishings from Middle Eastern countries, and more became highly fashionable items for those who could afford it, establishing design trends that have stayed with us since. As industrialization made using the designs and themes of different cultures possible in domestic production, a fascination for Japanese art and themes, for example, could be reproduced in consumer goods such as wallpaper, fabrics, porcelain, furniture, and other home goods.

The painters and architects of the Aesthetic Movement played an important role in the creation and popularity of the Turkish corner. British architect Owen Jones was one of the most influential figures in bringing the patterns and designs of the Middle East to the West. After embarking on his grand tour at 23, which included Egypt and Turkey, he became fascinated by the art and architecture of the region, as the Victoria & Albert Museum has documented. He ended his tour in Granada in Spain, where he and French architect Jules Goury spent six months studying the Alhambra, the magnificent palace left behind by the Moors. Jones made hundreds of watercolors and drawings of the ornamentation, architectural forms, and colors of this masterpiece.

When he came home, he didn’t feel the publishing methods of the day could reproduce the colors he painted, so he pioneered new methods of coloring in printing called chromolithography. The resulting work, “Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra,” is still regarded as one of the finest publications on Islamic architecture ever produced. The success of the work led to being commissioned to design the interior of the famous Crystal Palace, holding the Great Exhibition of 1851. Here he used color and pattern to great effect in a huge building of cast iron and glass.

After the exhibition was over, the building was re-created in southeast London, and it was here that Jones was able to create the Alhambra Court, a space whose decor incorporated Turkish design motifs. Over two million visitors a year toured the Crystal Palace, cementing the beauty of Islamic design in the public mind. And Jones wasn’t the only one to popularize the patterns and designs of the Middle East in the West.

Painters latched onto the allure and beauty of the region. The theme of this art was called “Orientalism,” a Western depiction of the East. Sir Frederick Leighton, William Holman Hunt, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema were among a large group of painters who turned to the Middle East for inspiration. Some of them had never been to any Islamic country but painted harem scenes with turbaned and bearded sultans and a bevy of beautiful, underdressed women in the cloistered harem, waited on and guarded by slaves. They reclined on pillows or bathed in sunken pools and were pampered and groomed until called by their masters. For the uptight Victorians, these scenes were colorful, sensuous, risqué, and exotic.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 turned America’s attention to the region. In 1876, the Centennial celebration in Philadelphia featured a large collection of artifacts of the Ottoman Empire. A love of the new and unfamiliar caught the American imagination, and a fascination for all things Middle Eastern grew. Style mavens touted the creation of a Turkish corner or, if one had the space and the money, a Turkish room.

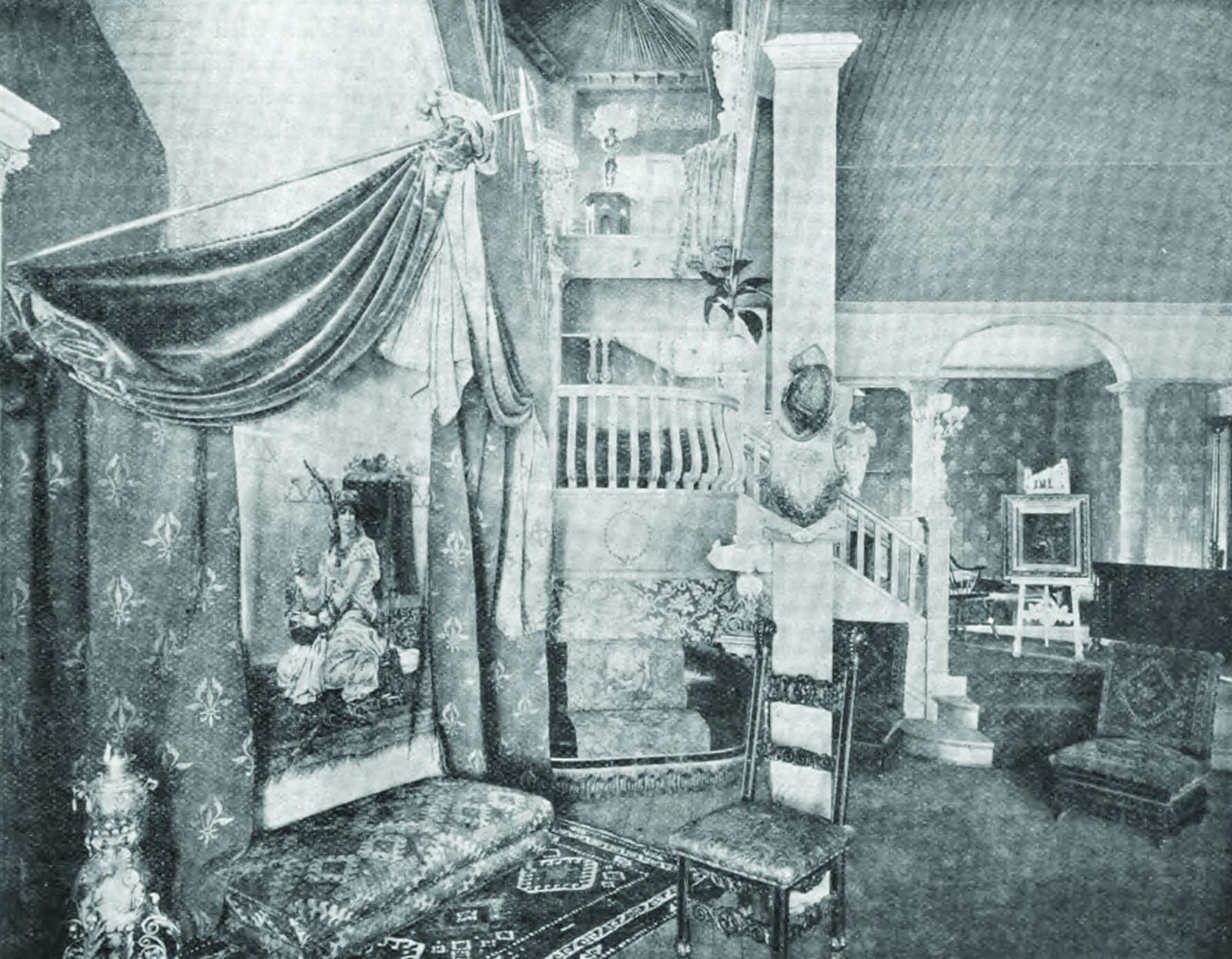

Usually the centerpiece was a low couch with dozens of embroidered and kilim pillows of every size and fabrication where one could recline and lounge. Added to this were layers of fine carpets, bright multicolored stained glass Moroccan lanterns, brass vessels, maybe even a hookah! Important elements of the look were mashrabiya, the intricately carved wooden lattice screens popular throughout the Middle East. These screens provided privacy while also allowing fresh air to cool a room and filter in sunlight. Mashrabiya were common themes in harem paintings, so of course a good Turkish corner or room had to have them, usually in the form of portable screens that acted as backdrops. Bone-inlaid patterned side tables, rich fabrics, geometric tiles, and Eastern tea sets completed the look.

The Turkish corner was the closest most people would get to the mysterious-seeming East, so as the popularity of the style grew, importers, manufacturers, and merchants came up with all sorts of unusual elements for people to add to their rooms, which could include things that had nothing to do with the cultures or products of the area. After all, “more is more.”

American artists such as Frederic Church took their own grand tours and fell in love with the area as well. They brought back paintings and sketches, design ideas, artifacts, and the talent to bring the Middle East to their own work in America. Frederic and his wife, Isabel, were world travelers who brought all sorts of items and ideas home.

One of the finest examples of this beauty can be found in Olana, Frederic Church’s home near Hudson, New York. The mansion, with beautiful views of the Catskill mountains and the Hudson River, is a treasure trove inside and out of Islamic themes, colors, and patterns, reflecting the Churches’ love of the Middle East. Frederic Church was one of the greatest artists in what is known as the Hudson River School of landscape painting. Today, the house and grounds are a state museum, regarded as one of the finest in the country.

Frederic and Isabel created a home filled with Moorish arches and windows as well as other complementary details inside and out. He created original stencils which he used to decorate the interior in beautiful colors and patterns. The bright colors and patterns he used on porch columns and other architectural elements of the house add to the visual treasure that is Olana. They created the ultimate Turkish room.

Like the Church family, if you were wealthy, it was possible to have not just a Turkish corner, but an entire room. In Troy, New York, John Paine, a very wealthy banker and industrialist had his architect create a Turkish room in the large mansion he had built in 1896. The room was used as his study. It probably never had the total harem look; the entire house is very masculine but features lavish Islamic architectural details on the fireplace mantel, the moldings, the ceiling and chandelier, and in the choice of a Moorish-arched window treatment. No doubt the floors were once covered with fine Oriental rugs and he may have had some Moroccan furniture as well.

Rooms and Turkish nooks were often seen as a place where a man could enjoy a cigar in peace, or a woman could recline and read or nap, but since most nooks or corners were in a heavily traveled part of the house, more than likely they were more decorative than practical. The corner became another set piece in the overall staging of a well-to-do home. They were simply a trend, which is why they dropped out of favor by the turn of the century, as decorating styles moved away from cluttered Victorian excess to simpler and lighter decor.

Today, true original Turkish corners are rare and typically found only in house museums, but everything in the world of design and decor always circles back into vogue. The popular “Boho style” incorporates many of the same elements. So, the Turkish corner has not completely disappeared, after all.

Related Stories

- The Story of Fretwork

- Albert Korber and the Business of the Artful Home

- From Practical to Ornamental: The History of Dressing Windows

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Love this!