House Proud: A Singular Bungalow in Prospect Park South

The owner of an iconic architectural wonder in Prospect Park South is dedicated to preserving its future.

Photo by Susan De Vries

Looking back, Gloria Fischer had no idea what she was getting into buying the house in Prospect Park South. The singular bungalow, Fischer’s first home in Brooklyn, came into her life through a wrong turn taken by her husband in 1972.

“A lot of people make a wrong turn and find this neighborhood that way,” she said.

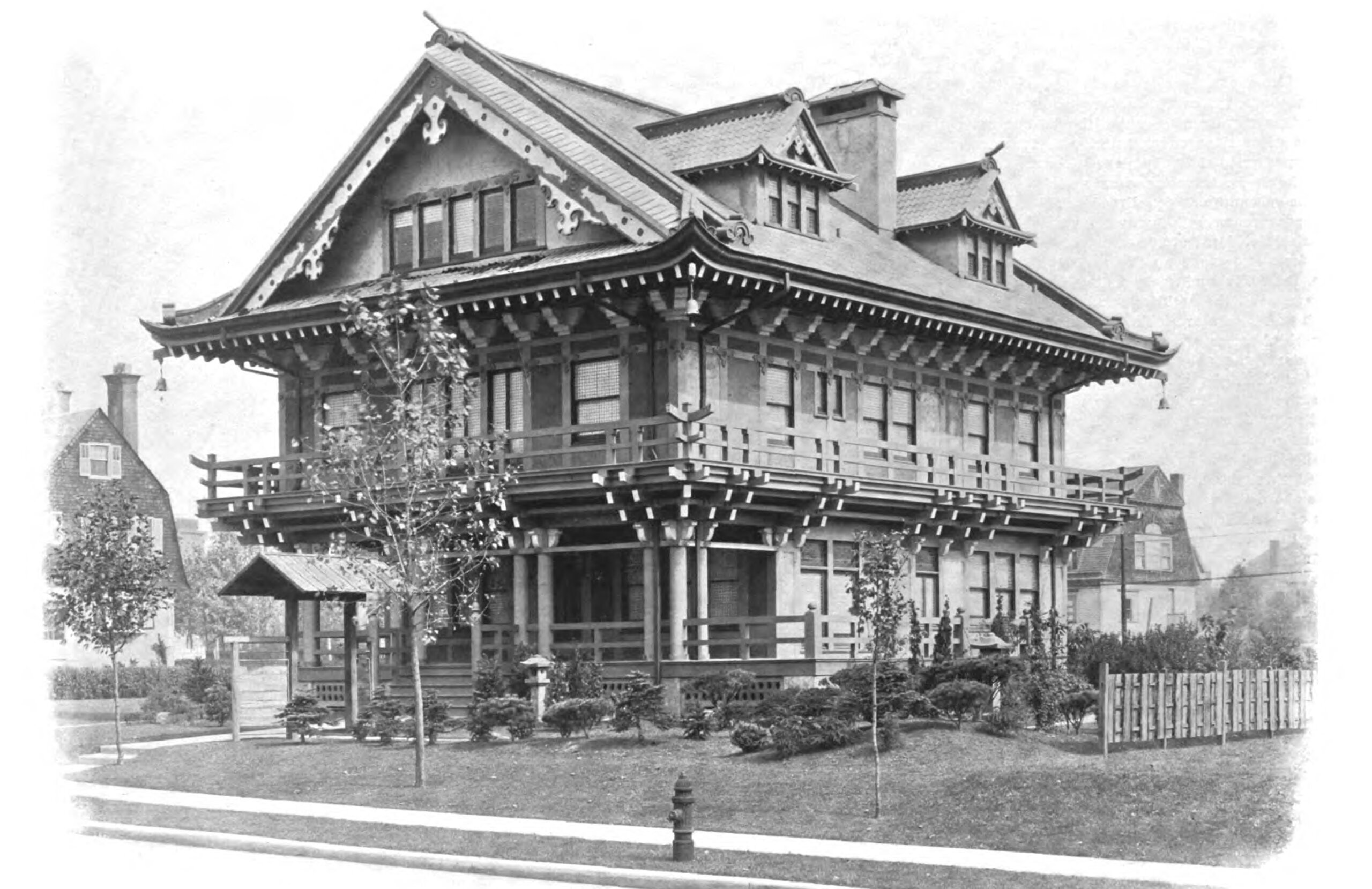

Fischer, who lived in Riverdale and had never been to the borough, said that at the time things were “really in sad shape” in New York City. When she discovered Prospect Park South, she was taken by the picturesque area with its interesting homes, particularly one known locally as the Japanese House.

It was always intended to stand out and attract the curious, with its bold and complex brackets, chrysanthemum carvings, and upturned roofline.

“There is no doubt that, and I call it this in a kindly, affectionate way, that this is an oddity. It was built to be an oddity to attract people,” she said. “I think, retrospectively, that I didn’t know what I was getting into fully because I have lived intimately with this house and it became something that I never, ever could have anticipated. The house makes unusual demands on you.”

The wood-frame house was the vision of Dean Alvord, a bit of architectural showmanship to demonstrate the suburban allure of the neighborhood he was carving out of former Flatbush farmland. Alvord purchased parcels of land in the late 1890s with the plan of creating what he called in promotional materials a “rural park within the limitations of the conventional city block and city street.” He installed streets divided by green parkways and constructed picturesque and generously sized single-family detached houses in an eclectic mix of architectural styles in the new community he dubbed Prospect Park South. An enthusiastic promoter, Alvord published booklets with exterior and interior photographs of the houses to lure buyers.

For the house on Buckingham Road, Alvord commissioned architects Petit & Green who crafted a Japanese-inspired bungalow of picturesque character ideal to snag the eye and gain some attention for his suburban project. Early advertisements and articles about the house make a point of noting the Japanese artisans involved with the project, including contractor Saburo Arai, garden designer Chogoro Sugai, and Shunsi Ishikawa who was responsible for the color scheme and decorations. What isn’t clear is any other information about the artisans; whether they were part of the growing Japanese immigrant community in New York or worked on other projects in Brooklyn.

When the Fischers arrived in 1972, they quickly got used to strangers’ curiosity about the house – and oftentimes their brazenness. Some would walk up the driveway and peek through the windows. One such onlooker, a “sparrow-like, bespectacled lady” found peeking through a living room window, has even become a sort of mascot or logo, appearing on postcards showing the house.

“I certainly gave into the movement and now that is my goal, my goal is really to share the house in as many ways as I can and that gives me a really good feeling,” Fischer said. “And of course its preservation has now become one of my major goals in life.”

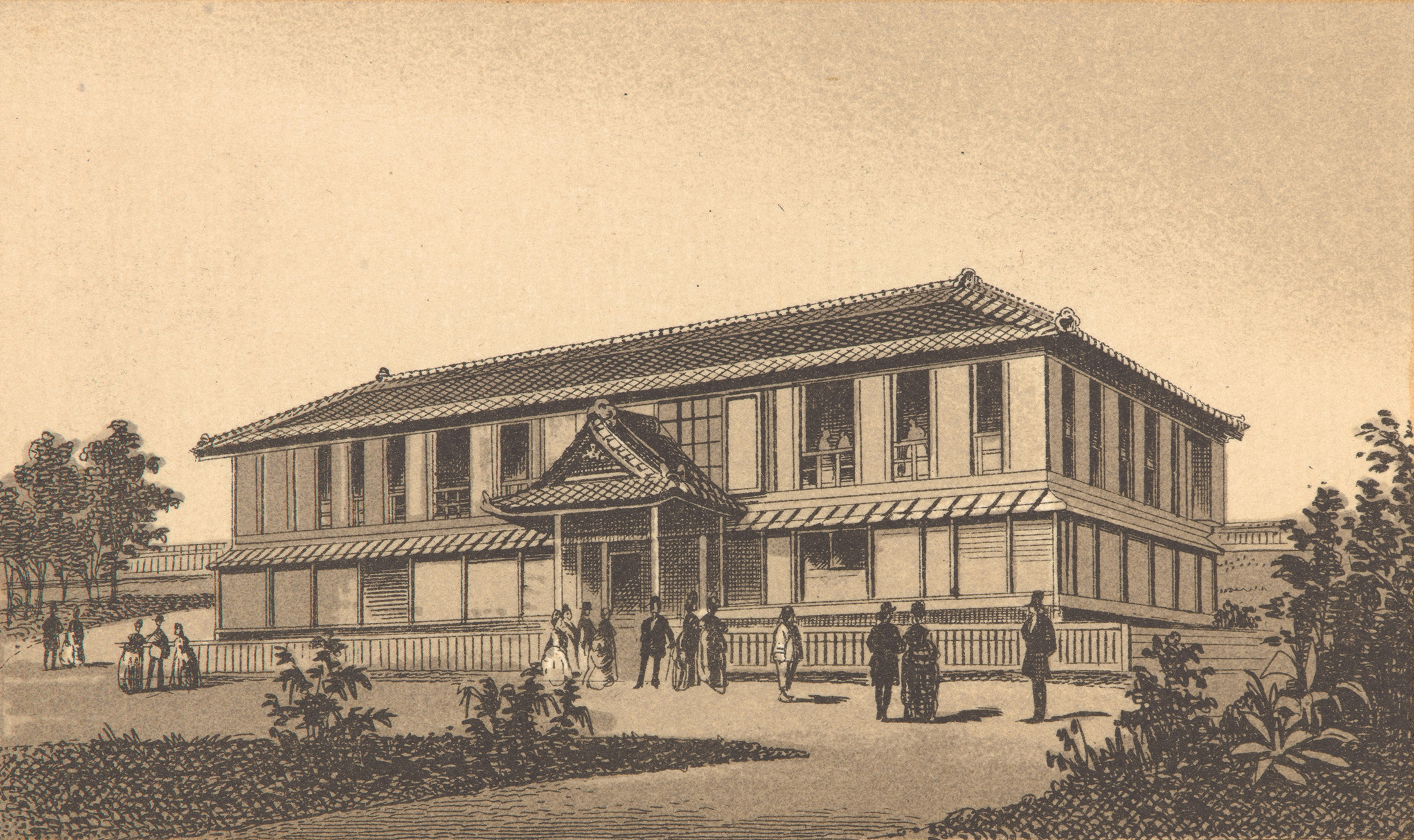

The dwelling certainly wasn’t the first Japanese-influenced structure of its kind in the United States. Enthusiasm for Japanese architecture and design emerged after the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which featured an official exhibit from the country. Japanese artisans and builders constructed a traditional dwelling, and a bazaar displayed Japanese wares and traditional garments, including kimonos, to fascinated fairgoers.

Exhibition and entertainment buildings, of varying degrees of cultural and architectural accuracy, were popular in Brooklyn. These included a Japanese house imported for display at an 1894 fair at the newly completed 23rd Regiment Armory at Bedford and Atlantic avenues and the early 20th century Japanese Village at Luna Park in Coney Island. In 1915, Japanese landscape design came to the nearby Brooklyn Botanic Garden with the opening of the Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden.

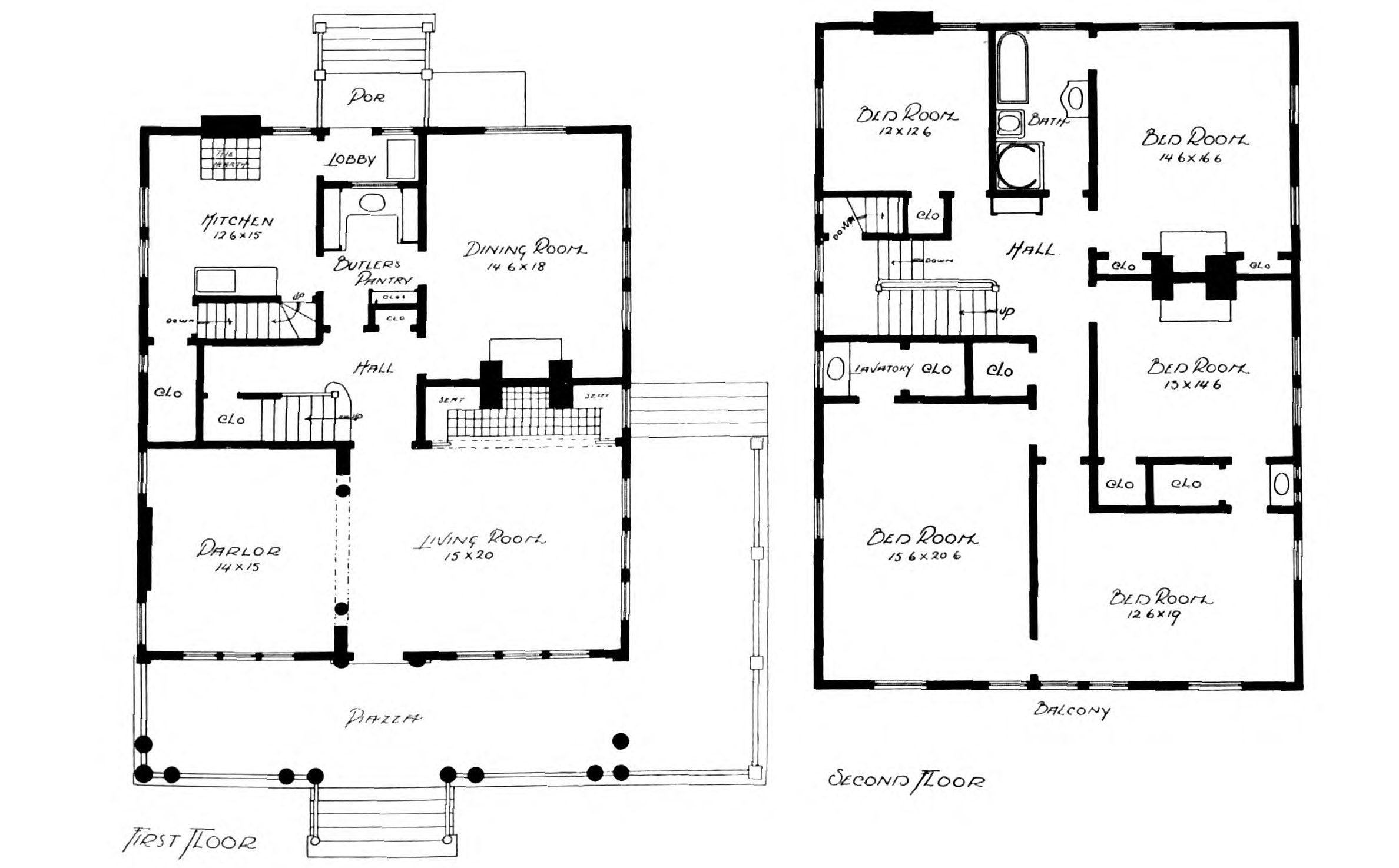

On Buckingham Road, the house created for Alvord in 1902 was really a marriage of Japanese-inspired design and an interior layout and conveniences that any Brooklynite of that time might have expected in a modern dwelling. That included a parlor, living room, dining room, butler’s pantry, and five bedrooms. While the dwelling received extensive press upon its completion, no early photographs of the interior have been uncovered, leaving only some detailed written accounts of the original interior features. An advertisement written by Alvord and published in 1903 as well as a 1904 article in Scientific American Building Monthly provide clues as to the extent of Japanese influence on the interior. Coffered ceilings included hand-painted designs incorporating irises, peonies, and storks; bathrooms were ornamented with Japanese tile; mantels were supported by carved figures; and dragons glimmered in stained-glass windows in the dining room and stair landing.

While the dragons are still to be seen, the hand-painted designs had disappeared by the time the Fischer family purchased the house. Other features had also given way to modern tastes, including the butler’s pantry and the columns that graced the parlor doorway. The original garden, which included curved walkways, Japanese tiles and lanterns, and a wooden gateway, had largely vanished. Perhaps more surprising is that so many architectural details have survived (including a third-floor billiard room) in a house that had at least seven owners prior to the Fischer family.

While Alvord was advertising the house for sale by 1903, it wasn’t until 1906 that the first family moved in. While it was on the market, it didn’t sit empty: Newspaper articles of the time show that Alvord permitted use of the house and grounds for fetes, musicals, and a meeting of the newly formed Prospect Park South Association.

The first owners of the house, Dr. Frederick Strange Kolle and his wife, Loretto, were perhaps the most famous residents, despite living in the property for just a few years. He was an early investigator into the possibilities of the X-ray while she was a fiction writer. The couple and their young children lived in the house only until 1908. The property passed through three more families and was foreclosed on once before being purchased by Abraham and Bessie Meskin around 1925. The pair would own the home until 1950, sharing it with an extended family that included their daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren.

Invariably when the building changed hands over the decades or when momentous family occasions made the local press, it was described as the “famous” Japanese house.

Fischer’s relationship to the unique house, where she and her late husband raised two children and keep their many belongings and those of her grandchildren, is multifaceted. “It’s a combination of things because it’s very personal, it’s very public. It’s a lot of contradictions. So that makes it interesting all the time. And, you know, I think to myself on and off when I’m doing something that’s house connected…this is not what most people do, and it absolutely tickles me, when I’m not worried about it,” she laughed.

Over the years, the memories that stand out are largely centered around the dining table, food, and family, she said. It was startling to Fischer when her children said they were old enough to start hosting holidays at their own homes.

“That stove,” she said, pointing toward the kitchen and its modern gas behemoth, “is one of the earlier commercials. It’s quite a baby. It was my husband’s favorite, I don’t even know what to call it, I can’t say it was a toy, because it wasn’t, it was serious. But it was his great connection. Because he loved food, and he loved cooking for everyone so those are my favorite memories.”

When asked why she has stayed in the grand house, with all the attention it requires, Fischer said she should be the one asking herself. “My children have asked me that question too,” she added.

“If I say that my identity became intertwined with that of the house, it sounds like it’s over the top. Along with that, I became all these titles that went with it: preservationist, Brooklyn historian…and the fact that I never run out of my, and I don’t know the right noun: interest, fascination, attraction.”

When Fischer first moved into the house, she took the only break she’s ever had from teaching to work in cultural events. She volunteered at the Brooklyn Museum and Brooklyn Academy of Music, where she started the children’s program. That volunteering led her to create her own cultural events business, which she ran for seven years before returning to teaching. Now she hopes to expand cultural programming for the house, helped by her grant writing know-how.

People from the borough and beyond flock to the house for tours and porch concerts that she organizes. Not too long ago a friend’s new neighbor, an architect, “just about begged” to see the house. “I was very anxious to meet him. I tell you that if he could have, he would have jumped up and down. It was such fun to watch his sheer pleasure, it was so wonderful.”

Once, an architect from Scotland wrote to Fischer about the house, and came to see it years later. “It was as if he were in a trance, he couldn’t believe he was really here.”

Part of the reason people can be continually mesmerized by the house, and the larger Prospect Park South neighborhood, comes down to the effort of locals – including Fischer – to get the area landmarked.

But despite the 1979 designation, all is not secure. Fischer is the first to say the Japanese House needs work, and that maintenance costs a lot of money. For the past 50 years, she said, she has done her best to keep everything in good condition, but now she needs help. “I need the real rehab of this building after 120 years to get done, period.”

“This is a typical preservationist plea so to speak, but special buildings should not rely on the good graces or the finances or whatever of one human being or even a small group of human beings, and that is the plight.”

Fischer said she has explored city grants and worked with the Landmarks Preservation Commission for funds, has reached out to Pratt Institute to explore ways to work together, and is currently contacting businesses in Industry City’s Japan Village. Fischer has just launched AirBnB tours of the house and is hoping to hold house tours for local business owners. “You name it, I have tried it. And I am still in that process.”

Any funding she gets will go towards the restoration of the house’s exterior. “The whole section of the house that is so beautiful, with its Japanese twists and turns and architecture, those are the hardest to keep in good shape,” she said. “They are also the most complicated to restore, given they must be carved by hand and with great care.” The house also needs a new roof. “It requires what a 120-year-old building requires, in the most general terms.”

Fischer’s goal is to guarantee the house will stand strong in the neighborhood for another hundred years and more, so new generations of Brooklynites can explore its history and use it as a creative hub. “I would like it to continue to undertake various cultural projects. I am always very excited when anything cultural happens here because I think that culture should happen in many places.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- The Weeksville Heritage Center Looks to the Future With a Focus on Art and Community

- A Bird’s-Eye View of Prospect Park South When It Was Young

- Prospect Park South’s Dash of Swiss on Rugby Road

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment