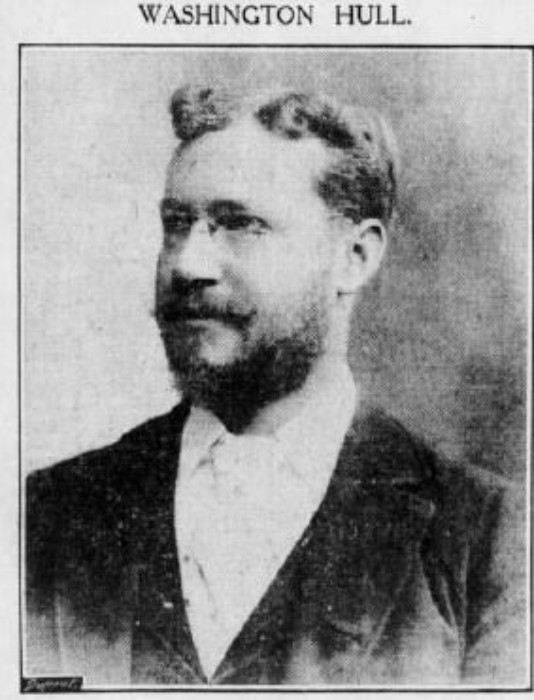

Walkabout: Washington Hull -- Brooklyn’s Forgotten Architect, Part 1

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story. This story is the stuff of novels and movies. A hometown boy, educated in Brooklyn schools, goes on to college and returns home, ready to perform Great Deeds in his chosen profession. He has some initial success working for the top company in his…

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

This story is the stuff of novels and movies. A hometown boy, educated in Brooklyn schools, goes on to college and returns home, ready to perform Great Deeds in his chosen profession. He has some initial success working for the top company in his field, he gets married to a beautiful woman and has five lovely children, and he is recognized in his profession as a rising star. One day he is asked to join a competition. If he wins, he will achieve one of the greatest pinnacles of his profession’s success, and he will be a household name. Against all odds, and against incredible competition, he wins, and his name is plastered all over the papers. But before he can proceed with his project, he is shot down by political machinations, his name is stepped on, and his star falls rather rudely to earth. What happens next is both tragic and mysterious. That, in a nutshell, is the story of Brooklyn architect Washington Hull.

I’ll admit it, I had not heard of Washington Hull, and had never come across his name in my research into Brooklyn’s buildings before. At least his name never registered. That’s mostly because he didn’t design very many buildings in Brooklyn. I certainly would have remembered his name if his greatest design had been built, but now I’m getting ahead of myself and the story.

Washington Hull was indeed a Brooklyn boy. He was born in 1866, the son of John Henry Hull, a prominent attorney from an old New England family. He grew up on Prospect Place and attended public school. He graduated from Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, where he was known as a star athlete, as well as a good student. He then went on to Columbia, where he studied architecture and minored in sports. He was a champion rower who led his crew team to a record breaking victory over Yale.

As a young man coming out of college in 1882, he seemed to be golden. He was a good student, a popular athlete, a fine artist and draughtsman. His first job was with the firm of C.C. Haight, and then he landed his dream job, a position with McKim, Mead & White, the most important architectural firm in the country. By 1895 he had been made the manager of the firm’s draughting room; a demanding position, as the firm’s many commissions had to have drawings and blueprints by the thousands, all perfect and accurate, and on time. And all by hand.

Around the same time he and two of his coworkers, James Monroe Hewlett and Austin W. Lord, decided to start their own firm. Washington may have known Hewlett at Columbia, as well as at McKim, Mead & White. One of Lord, Hewlett & Hull’s first commissions was a high school in Stapleton, Staten Island. From there, bigger and better works came their way. The young firm came in second in a competition to choose an architect for the new Philadelphia Museum of Art. Rumor had it that they almost came in first. The men brought home a $3,000 second-prize purse. Even though they didn’t win, it was quite a coup for such a young firm. The job went to Horace Trumbauer, a Philadelphia architect.

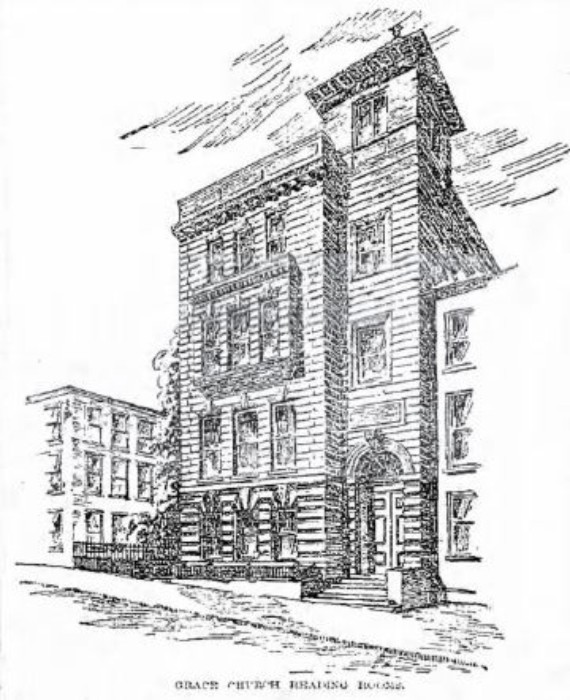

Soon afterward, they got the commission to design the new Reading Room for Grace Episcopal Church in Brooklyn Heights. This building was the gift to the church by William Low, one of its wealthy parishioners, and the step-brother of Seth Low, who was President of Columbia College, around this time. The building was designed to house a library, reading and class rooms, and an auditorium that could also be used as a drill room and gymnasium. The Grace Church Reading Room building was a fine success, and still stands at 62 Joralemon Street.

Lord, Hewlett & Hull designed a few other private homes and other buildings, and entered, but lost several prominent competitions, including one to design a new tower for Brooklyn’s City Hall, which had lost its tower in a fire. They lost, so were quite pleased when they got word of another competition. This one was for Senator William A. Clark, the Copper King, one of the richest men in America at the time. Clark had recently moved to Manhattan from Montana, where he had been a one-term Senator. He was looking for architects to design his mausoleum in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

The boys entered the competition and won. Clark took a liking to these bold and imaginative young men, and was very pleased with his final resting place. But before he rested there, he wanted to build the largest mansion in New York City, and live out his days in urban splendor. To everyone’s surprise, and probably every other architect’s chagrin, he offered the job to Lord, Hewlett & Hull.

William Clark was the quintessential Robber Baron, a very successful man who had grown up poor, and was determined not to die that way. He ended up in the railroad and mining business out West, where he controlled copper and silver mines and the railroads that served them, as well as electric power plants and more than one newspaper.

He got rich the old fashioned way; he connived, stole, cheated, foreclosed, extorted and bribed his way into a massive fortune. He bought a Senate seat, served for one term, which allowed him the privilege of being called “Senator” for life, and then decided to leave Montana, and live it up in New York. Mark Twain wrote about the Senator, declaring that “he is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a ball and chain on his legs. To my mind he is the most disgusting creature that the republic has produced since Tweed’s time.”

Clark moved to New York in 1895, the same year Washington Hull and his partners were enjoying their first successes. He really didn’t care what people thought of him. He would show them by building a house on 5th Avenue, home to Manhattan’s richest men and fellow robber barons. He wanted the biggest, most splendiferous chateau 5th Avenue had ever seen, and he had the bottomless pockets to pay for it.

The mansion would be home to Clark and his five living children from his first wife, Katherine. She had died in 1893. Clark also came to New York with a ward named Anna Eugenia La Chapelle. She was a budding actress born in the city. Society was shocked when it became apparent that their relationship was more than that of a father figure and his daughter. In 1901, she got pregnant, and again in 1903. Clark said they got married in 1901, but no documentation was ever found. In 1901, Anna was 23, and William Clark was 62.

Clark bought a huge plot on the corner of 77th Street and 5th Avenue. The mansion commission was an architect’s dream, although it came with the client from hell. James Hewlett and Washington Hull came up with the initial design for the mansion. They presented it to Clark, who loved it. Then he started making changes. The massive mansion just wasn’t big enough. The New York Times reported that the plans were constantly being revised as the designs were not “sufficient in size or splendor.”

Initially, it was supposed to cost $417,000, but the costs just kept rising as the design changed and grew. Clark decided that the planned art gallery wasn’t big enough, so he bought the land next door so the building could be expanded to the proper size. The price to build this palace was now at $2.5 million. The house was a huge Beaux-Arts palazzo, tall and ostentatious. It sprawled along 5th Avenue, and by the time it was done, was nine stories tall and had 121 rooms. The cost had also risen to $10 million.

It was an endless project that ended up taking 13 years to finish. It was Washington Hull’s job to keep track of expenses. Clark was stinking rich, but he was also a penny pincher. The chateau was to be constructed out of marble blocks, but the quarry in Maine was playing hardball. They had originally quoted a price of $200,000 for the stone, but when the project expanded, they raised their quote to $600,000.

Clark wasn’t having it, and neither was Washington Hull. He told Clark that similar marble was available at a nearby quarry and all told, would cost $400,000. Clark bought the quarry, and built a private railroad track to bring the marble down to NY. Hull spent nearly two years, going back and forth from Maine to New York. He ran the quarry as an operation with a client list of one. Similarly, when the bids for bronze works were too high, Clark purchased the Henry Bannard Bronze Works, and sent them copper from his own mines.

As work on the Clark mansion continued, the relationship between Hull and Lord & Hewlett began to deteriorate. They severed their partnership, even though they still had several projects in the works. They continued those projects, like the Clark mansion, as independent business entities. Whatever came between them was a battle between Washington Hull and James Hewlett. The enmity would last for the rest of their lives.

Meanwhile, Washington Hull was eager to move on to the next project. The drama of building the Clark mansion was all behind closed doors. The public and the newspapers still thought Washington Hull was the toast of Brooklyn. Everyone, especially in the Society pages, was still gushing over him as a native son at the peak of his ascent. They also loved his wife, Julia, who was a gracious hostess and a very talented pianist and musician. She hosted a number of parties and fundraisers both in their home at 154 South Portland Avenue, or in one of the many clubs and organizations they both belonged to.

In 1902, William Hull was among a select group of architectural firms who were invited to enter a competition to design a new Municipal Building for the Borough of Brooklyn. The old building, which stood where the present Municipal Building still stands, was just too small and its design too antiquated. Brooklyn wanted a magnificent new building to complement the newly restored Borough Hall, the Beaux Arts Hall of Records Building and the Kings County Courthouse, all on the block of Joralemon Street between Court Street and Boerum Place.

The competitors for the prize included Washington Hull, Lord & Hewlett, Woodruff Leeming, Rudolfe L. Daus, William Tubby, the Parfitt Brothers and several others. There was a lot of talent in that room, but after all of the designs, renderings and models were submitted, miracle of miracles – Washington Hull was declared the winner. But like the Clark mansion, would this be another case of “be careful what you ask for, you may get it?” More next time.

Read Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment