Walkabout: The Three Graces of Brooklyn, Part 3

General Benjamin Franklin Tracy, General James Jourdan and Mr. Silas Dutcher were known as the “Three Graces” back in 1870s Brooklyn. The three of them, all elected officials, had Brooklyn and the Republican Party firmly in their very competent and powerful grasp. Working together, as the state’s attorney, police and health commissioner, and chief tax…

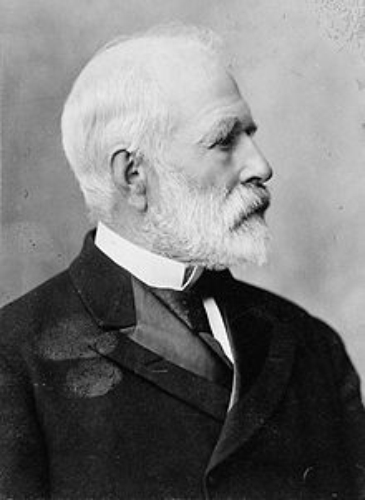

General Benjamin Franklin Tracy, General James Jourdan and Mr. Silas Dutcher were known as the “Three Graces” back in 1870s Brooklyn. The three of them, all elected officials, had Brooklyn and the Republican Party firmly in their very competent and powerful grasp. Working together, as the state’s attorney, police and health commissioner, and chief tax collector, respectively, these men were able to control not only their political party but the affairs of one of the nation’s fastest growing cities. The United States was recovering from the Civil War, and industries once making weapons and war materials were now making consumer goods for a new middle class that wanted to buy. Brooklyn’s factories were humming, and thousands of immigrants and native born people were pouring into the city, coming here to work and live, joining the population already here. It was an exciting time to be in Brooklyn, but it was also a time when crime, corruption and urban ills were on the rise. Strong leaders were needed, and the men known as the “Graces” were in the perfect position to gain and hold power.

Chapters One and Two of our story tell of the backgrounds and rise to power of these three men. By 1871, Brooklyn was theirs. It was in their power to appoint their people to positions of influence, to get men they didn’t like out of their positions, and to bestow choice assignments, jobs and blessings all across the bloated bureaucracy of city government. Politics hasn’t changed much before or since that time, and although the speeches and objections back then were delivered more colorfully in top hats and morning coats, the sentiments were the same as today’s. In 19th century Brooklyn, the key to power lay within the wards, those small political neighborhoods we now call City Council districts.

A look at the Brooklyn Eagle during the early years of the 1870s shows that while the Graces held power, there was strong opposition to them from not only the Democrats, who were totally shut out, but more from disaffected Republicans who didn’t like the Graces, or their rule. They waged pitched battles at City Hall, Party headquarters, and in the halls of the State legislature, where the big money was. The fighting was ugly, and the press loved every contentious minute of it.

The men running the Brooklyn Eagle didn’t like the Graces, either; their writers referred to them by that nickname, which they more than likely hated, all the time. They also called them the “Fast Friends,” reporting how their individual and collective influence had forced men from their jobs or caused others to vote the way the Graces saw fit. One article from Nov. 21, 1871, called the men the “Radical Reformers: Jealous Jourdan, Duplicity Dutcher, and Tricky Tracy.”

The article goes on to say that Silas Dutcher, Supervisor of Internal Revenue, used his high position in the Dutch Reformed Church to paint himself as a pious churchman doing God’s work in the messy business of politics. By bringing his religion with him into the boardrooms, he unduly influenced gullible churchmen in politics, and the rest of Brooklyn faithful, to support him and his positions. The paper said, “Dutcher’s forte lies in the happy faculty of adapting himself to present surroundings. In his devotional duties, none are more earnest – in the intrigues and tricks of a ward contest, none more active. With a somewhat remarkable facility, he throws off the garb of a devout churchman to don the motley of a ward trickster, and with equal ease returns to his religious endeavors.”

The paper didn’t come right out and say it, but the article strongly implied that Dutcher bought votes by using his contacts in the Navy Yard to send sailors out to “influence” voters, and by outright fraud, by having his ward contacts change votes logged in the official books. They couched their accusations in hypotheticals, but it was right there in black and white.

James Jourdan fares a bit better, but not by much. As a former soldier, he was portrayed as the muscle in the Grace’s organization, his police headquarters filled with burly enforcers who could be turned out into the streets when necessary. The paper said he was probably the “most honestest” of the three, but certainly not the smartest. He was the snarling pit bull in the yard of the Grace’s headquarters. As Brooklyn’s top cop, he was said to be the man who would go down to Irishtown, near the Navy Yard docks, and have his men confiscate legitimate distillers’ barrels of liquor, and then extort “taxes” from them in exchange for their return. According to the paper, his headquarters was filled with toadies drawing lucrative salaries as clerks, who were required to pay kickbacks for the privilege, in an office that didn’t need many clerks.

General Tracy was regarded by the paper as the ringleader and the most egregious of the trio. This particular article didn’t go into detail about all his offences, as it said that “it was unnecessary to go into any extended notice of this man, who has been so thoroughly ventilated by the Eagle over and over.” Previous articles go into excoriating detail of Tracy’s offenses, which boil down to influence peddling, and the making of huge profits from his position on the bench as the State’s Attorney for the Eastern District. They implied that his was a bench for sale, and it had been sold over and over again.

The Three Graces controlled Brooklyn’s politics throughout President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration, which ended in 1877. Despite what the Eagle wrote, or what their opponents said, their positions and power remained intact. Whatever their faults or sins, the three men ran Brooklyn well. They may have taken their individual and collected blows, but they were never indicted or formally accused of anything untoward. It was all politics, speculation and innuendo. While in office, they were all participants in greater Republican political doings, acting as representatives to state and national conventions.

Interestingly, their party success didn’t translate into local public office. Tracy would run for mayor in 1881, and come in third. Silas Dutcher ran for the city’s Register office, a plumb political prize, and lost. But the appointments for all three, and fortunes as well, kept coming, before and after they exited city political life.

General Jourdan became not only the president of Brooklyn’s police department in 1872, he was also made sole Commissioner and President of the Board of Excise. That year, he was also appointed as the Commissioner of the Board of Health, a position he held until 1884. After leaving public life, he went into business and became a very wealthy man.

By the time he died, at the age of 79 in 1910, he had risen to the office of President of the Brooklyn Union Gas Company. He was a trustee in the People’s Bank of Brooklyn, a Director of the Mechanics Bank of Brooklyn, the National Copper Bank of New York, the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, the Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company, the Subway Realty Company, the Interborough-Metropolitan Company, the New York and Long Island Railroad Company, and several other realty companies on Long Island. He had also been on the boards of several other gas companies that all merged to become Brooklyn Union Gas under his tenure. He died of diabetes at his home at 174 Washington Park in Fort Greene. His son succeeded him as president of Brooklyn Union Gas.

Silas Dutcher also fared well. His further government appointments included the office of Appraiser of the Port of New York. He had received the most grief from the press, but is credited for being the only one of the three who came out of public office without having made a large personal fortune. He made his money on his own, in private life. And he did really well. He went into banking, becoming a charter trustee in the Union Dime Savings Bank of New York, and became its president in 1885.

In 1891, he was made president of the Hamilton Trust Company of Brooklyn, an office he held until his death. He was also the director of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company of New York, the director of the Garfield Safe Deposit Company, the German-American Real Estate Title Guarantee Company, and the Kings County Electric Light and Power Company. He was treasurer of the Columbia Mutual Building and Loan Association, and president of the Ramapo Water Company. Dutcher was also a fervent proponent of a Greater New York City, and was on the board to consolidate the boroughs into one city.

The Dutcher family commissioned architect George P. Chappell to design a home for them at 196 New York Avenue, a large brick mansion that still stands in Crown Heights North. Silas Dutcher died at his home of a stroke, tragically on his 50th wedding anniversary in 1909. His family had planned a large gala for that evening, one that sadly became a wake. Silas Dutcher was 80 years old.

General Benjamin Tracy went on to bigger and better things, as well. He was always the biggest political animal of the three, and wanted to run for higher office. In 1881, he was appointed to the New York Court of Appeals for a year. He also ran an unsuccessful campaign to be his party’s candidate for mayor of Brooklyn. When he left Brooklyn politics, he went back to his very successful law practice, until the day that Washington, D.C. and the President of the United States called.

In 1889, Tracy was confirmed as Secretary of the Navy, under President Benjamin Harrison. He held that position until 1893. Tracy is credited for the creation of the “New Navy,” a fighting force that was able to be used for offense, not just the coastal defense or to dispel pirates and raiders, which had been the Navy’s role since the Civil War. Under Tracy’s watch, the Navy commissioned its first modern warships in 1890 and 1892, the battleships USS Indiana, USS Massachusetts, USS Oregon and USS Iowa.

While he enjoyed these successes in office, Tracy’s personal life took a major blow, as both his wife and one of his children died in a house fire in Washington in 1890. After leaving the Navy, General Tracy went back to New York, and re-opened his law practice. In 1896, he defended New York City Police Commissioner Andrew Parker against Commission President Theodore Roosevelt on charges of negligence and corruption. He won, embarrassing Roosevelt badly. He also helped negotiate a settlement to a boundary dispute between Venezuela and Great Britain.

In 1897 he ran for the office of the first Mayor of Greater New York City, after consolidation. He came in third, behind Democrat Robert Van Wyck and Citizen’s Union party candidate Seth Low. That was the end of Mr. Tracy’s political ambitions. He died in 1915, back home in Tioga County at his farm. He was 85 years old. The last of the Three Graces was gone.

(Photos of 174 Washington Park and 196 New York Avenue: PropertyShark)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment