Walkabout: The Queen of the Oldest Profession in Troy

Yesterday was May 5th, Cinco de Mayo, for millions, and also the anniversary of the death of one of Troy’s most colorful and interesting people. Her name was Mary Alice Fahey, but everyone in Troy knows her as “Mame Faye.” She ran Troy’s most famous house of ill repute for over forty years, and was…

Mame Faye, allegedly, as there are two disputed photos of her around. Photo via Duncan Crary Communications

Yesterday was May 5th, Cinco de Mayo, for millions, and also the anniversary of the death of one of Troy’s most colorful and interesting people. Her name was Mary Alice Fahey, but everyone in Troy knows her as “Mame Faye.” She ran Troy’s most famous house of ill repute for over forty years, and was famous throughout the Capital Region. Her bordello was in the heart of the city’s Red Light District, called “The Line,” right across the street from the railroad station.

Since the police station was only three buildings away, it’s not like the law and the people of Troy didn’t know The Line was there. What Mame Faye and her colleagues were doing was not legal, even though it was advertised in the papers. Of course, a flourishing sex industry was NOT what the Collar City’s civic leaders wanted to perpetuate, or be proud of. But then, it wouldn’t be a story if there weren’t some drama.

Mary Alice Fahey was born in 1866, the child of Thomas Fahey and Margaret McNamara Fahey. They were two of the thousands of Irish immigrants who had made their way to Troy in the middle of the 19th century, drawn there by the factory jobs in the iron and textile industries that gave Troy her tremendous wealth. Troy was one of America’s richest cities, a jewel of wealth and industry on the Hudson.

The Burden Ironworks, and other heavy industrial plants in the south of Troy were joined by the many large and small textile, sewing and laundry factories that produced fabrics, shirts, clothing, and most importantly, the detachable stiff cotton collars that were a necessary staple in the wardrobe of just about every man in the country with a dress shirt in his closet. The collar industry was so lucrative and so large; Troy would soon be called the Collar City.

Historians don’t know much about Mary Alice Fahey’s parents or her early years in Troy. The Irish made up the bulk of the factory workers in Troy, most toiling under conditions that would be intolerable now, for wages that just allowed them to survive. No one really knows what Mary Alice was doing, or where she was working, but by the turn of the 20th century, she had gotten married to a man named G. A. Bonter, and was listed in the census records as Mrs. Mary Bonter. They either parted company, or he died or left town, or never even existed, because he is not even enough of the story to have a first name. Mary listed herself as “single” or “widowed” on the 1910, census and there afterwards.

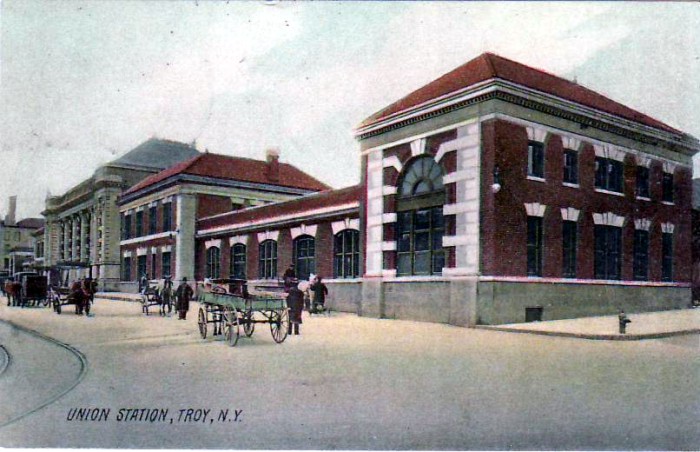

In 1904, a woman named “Mame Fay” (there are several name variations) was arrested for “disorderly conduct” during a sweep of the bordellos on The Line. Perhaps that was what inspired Mame to open her own establishment and go from worker to management. In 1906, she purchased the first of her establishments, a house at 1725 Sixth Avenue, in the heart of the Line. This was a line of row houses directly across from the railroad tracks, near Union Station. By all accounts, it was a rundown area; the noise and soot from the trains made it undesirable for most people, although it was in the heart of downtown Troy.

Mame’s house was only three doors down from the Troy Police Headquarters. Her house, and the other establishments on the Line, was in the perfect place to attract business. Troy was a major travelling hub, a crossroads for New Englanders coming west to do business in upstate NY, or to travel south to NYC. The military used Troy as a way station for the same reasons, and the mostly male students of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute passed right by the Line on their way up the hill to the RPI campus. In fact, the main stairway to the college was right behind Mame’s house. How convenient!

Some of the other bordellos on the Line were run by equally colorful characters with professional names like Jew Jenny, Big Flo and Little Flo. There were houses that catered to all persuasions and racial and ethnic groups. They were all part of an industry that was tolerated and winked at while being blasted from the pulpits and during City Hall meetings. The police were right down the street, and local lore has it that several of the officers moonlighted as bouncers while off duty.

By the 1920s and ‘30s, Mame Faye’s house was firmly established, and was doing great, as was the entire block. Prohibition had only increased business, as it was pretty easy to get liquor in a city that wasn’t all that far from Canada, and had the Hudson River flowing by it, which connected to the Erie Canal, which connected to the Great Lakes, and well, you get the picture. World War I had brought a lot of soldiers through Troy, as well, and they had spread the word, too.

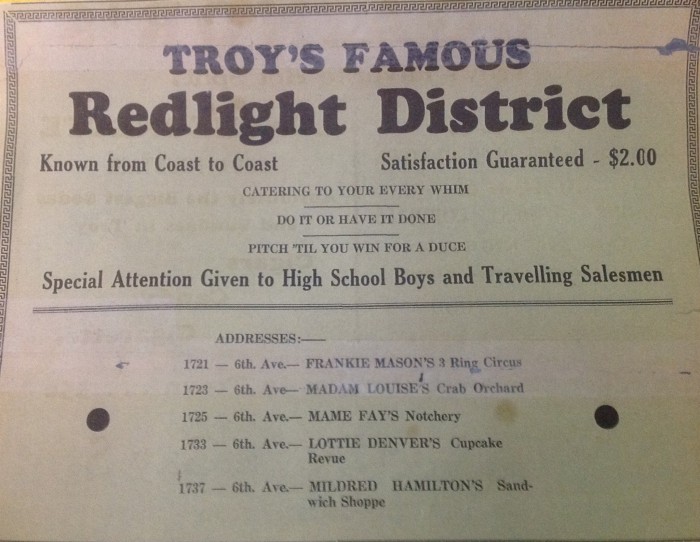

In the 1930s, a flyer printed in the local paper advertised Troy’s now infamous Red Light District. The area’s five houses of prostitution were all listed with their addresses and names. The flyer read,

Known Coast to Coast Satisfaction Guaranteed – $2.00

Catering to Your Every Whim

Do it or Have it Done

Pitch ‘Til You Win for a Duce

Special Attention Given to High School Boys and Traveling Salesmen

ADDRESSES: –

1721 – 6th Ave. — FRANKIE MASON’S 3 Ring Circus

1723 – 6th Ave. – MADAM LOUISE’S Crab Orchard

1725 – 6th Ave. – MAME FAY’S Notchery

1733 – 6th Ave. – LOTTIE DENVER’S Cupcake Revue

1737 – 6th Ave. – MIDRED HAMILTON’S Sandwich Shoppe

Mame Faye’s bordello operated until the 1940s. During that time, she successfully fought off attempts by the city to close her down, but she had the money to hire an excellent lawyer. But finally, in 1941, she and the other houses on the Line were shut down by a crusading District Attorney named Earl Wiley, who campaigned to clean up a corrupt and socially dissolute Troy. Mame Faye retired, and died two years later, on May 5, 1943, at the age of 77. She left her nephew a tidy fortune of almost $300,000, which would be $3.5 million today. She is buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, in the Fahey family plot. She left $2,500 for a headstone, but one was never put up until 2006.

The block that made up the Line was torn down in 1952, in the first of Troy’s attempts at urban renewal, a disastrous demolition policy that would end up taking out Union Station and a third of Troy’s historic downtown, by the time they were finished. Physically, the city has never really recovered, and people who lived through those days still shake their heads, and wonder what the city was thinking. Union Station was beautiful, and was favorably compared to NYC’s Grand Central Station.

As for Mame Faye, her story made her legend. There are a multitude of stories about her, passed along among Trojans for generations. We do know for a fact that she was very generous with her money. She gave money to the church and to other charitable causes. But most of her personality and life story is now enshrined in the classic “hooker with a heart of gold” legend. She was said to be bawdy, witty, and very smart, as well as a devout Catholic and a maternal figure to her “girls”. There are tales that once, while taking a big bag of money to the bank, a woman called out to her, “”Hey Mame, how’s business?” Mame shot back immediately, “It’d be a hell of a lot better if it weren’t for amateurs like you!”

Another tale has her going to local shops, department stores and luncheonettes and asking the sales girls how much they were making. When they reported their pitifully low salaries, she told them, “”Honey, don’t you know you’re sittin’ on a million? You should come and work for me!” That story led to the title of a documentary about Mame Faye called “Sittin’ on a Million,” released in 2008 by filmmakers Penny Lane and Annmarie Lannesy. They reported that Mame Faye’s story is now the stuff of Troy legend. The above story has also been attributed to another local madam in another town. Did Mame Faye ever really say any of that? Who knows, it’s still a great story.

Every city seems to have a beloved local madame who may have been reviled and vilified in her day, but now is a colorful part of local history. The popularity of these characters also calls into speculation the entire sex industry and its place in American history. Why are the hookers of the past colorful and the topic of song and legend, while today’s prostitutes are merely criminals? Something to think about.

Mame Faye, for better or worse, is a part of Troy’s storied history, and was celebrated last night, as Troy’s downtown food and drink establishments had a “Cinco de Mame” evening, with red lights put up in many of the restaurants and bars to commemorate Mame Faye and Troy’s long-gone Red Light District. She probably would have loved it.

(Many thanks to Duncan Crary for the idea for the story, as well as the photographs and links to source materials. Troy would be much less without you.)

Wonderful story, MM!

“Special Attention Given to High School Boys and Traveling Salesmen” and “Pitch til you win” ? Dear god. How quaint. 😉