Walkabout: The Master of the Pangymnastikon, Avon C. Burnham, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. Here in Brooklyn, once sedentary office workers, executives and stay at home moms were picking themselves up from their seats and going to the gym. There, they worked out on exercise machines, used specialized gym equipment, ran around the track, or performed aerobic exercises in a class with other…

Read Part 1 of this story.

Here in Brooklyn, once sedentary office workers, executives and stay at home moms were picking themselves up from their seats and going to the gym. There, they worked out on exercise machines, used specialized gym equipment, ran around the track, or performed aerobic exercises in a class with other peers. They also insisted on having their children participate, as well, so the gym had special classes for children. After a few hours of exercise, showering and primping, they would exit onto the street, catch an omnibus, trolley, or walk home.

It was exhilarating to feel the blood rushing to their cheeks as they glowed with health. For the women, all of that exercise also made it much easier to tolerate being wrapped up in a whalebone corset, with petticoats and bloomers under their skirts, a bustle of fabric on their bums, and a skin tight bodice and jacket buttoned up under their chins. After all, this was the modern age, and the fashions of 1870 were quite demanding.

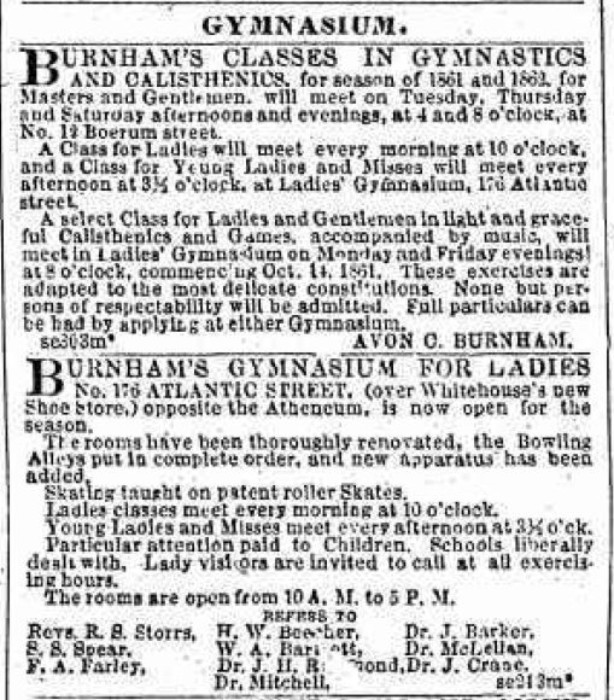

Yes, the modern fitness craze that we think we invented is much older than we thought. Brooklyn’s first public health club and gymnasium was not a Bally’s Fitness, Crunch Gym or New York Athletic Club, it was Avon C. Burnham’s Academy of Physical Culture and Gymnasia, by 1870, located in a large building on the corner of Schermerhorn and Smith Streets. The Academy was run like a university of fitness, with classes, instructors, and all of the latest equipment. The Headmaster of this institution was a young man of boundless energy. He was not a large man but he was fit and filled with an almost missionary zeal to make sure that the budding couch potatoes and delicate flowers of his day became strong and athletic citizens of the world. There was no one like Avon C. Burnham in Brooklyn, before or since.

Part One of his story was told here. By 1870, Burnham had gone from renting the upstairs of an establishment a couple of blocks away on Boreum and Fulton Street as his gymnasium, to building this large temple of fitness, which stood where the black and grey striped MTA building now stands. His new facility was a state of the art fitness center, with enough room for separate classes for men, women and children. He was going after the elite; his ads boasted that “none but persons of respectability would be admitted.” He had all of the latest gymnastic equipment, including climbing ropes, parallel bars, balance beams, and horses. He set up a room for all of this equipment called his “pangymnastikon,” where many disciplines could be worked on at once, a room that looked like the practice room for a 19th century version of Cirque Du Soleil.

Burnham believed not only in physical fitness, but cultural fitness, as well. His classes had periodic exhibitions for families and friends, where members of his classes would dazzle the audience with their gymnastic prowess and talents. Like today, every parent there beamed when their child demonstrated skill in floor exercise or tumbling, and they all gasped and clapped to see gymnasts swing on the parallel bars or perform routines on the ropes or perform routines of grace and strength on the horse. Burnham also had other performances where the audience enjoyed an evening of music, poetry and dramatic reading. Avon especially liked dramatic readings, and was well known around Brooklyn for his skill in this activity, as well. He was a well-rounded guy.

Unfortunately, as any modern gym owner will tell you, it takes a lot of bodies using your facility to stay open. By 1873, Burnham’s gym was having financial problems. An announcement in the Eagle in September of that year declared that “Avon C. Burnham is determined that institution shall not fall to the ground while he is anywhere near to look after it.” The announcement went on to say that the facility had been upgraded, new equipment was in place, and they looked forward to welcoming the members of the city’s finest families to their classes. Avon C. Burnham was positive that this would be the institution’s finest year ever. It would be one of the few times he was wrong. By 1874, he was in bankruptcy court, and was forced to close the gymnasium and sell the building. His gym was sold to the local German Saengerbund, a singing society and social club.

Burnham may have been down, but he was hardly out of the game. Losing his building only made it easier for him to be more mobile, offering his services to other institutions, and actually becoming busier than ever before, as well as more popular. Burnham became a consultant to some of Brooklyn’s most prestigious institutions, a traveling preacher spreading the gospel of physical fitness, and instructing his new students in the many ways to achieve physical perfection.

Physical culturists, as people like Burnham were called in his day, had figured out much of what we now regard as basic Phys. Ed. curriculum. Of course, there was running and walking and they knew about the positive results of aerobic exercise, although they didn’t call it that. Getting the heart pumping and the blood flowing was key, so they practiced many of the floor exercises that became quite familiar to us as school children; jumping jacks, pushups, windmills, and the like. They also saw that walkers and runners often did not have toned upper bodies, so they instituted strength and resistance training exercises to build torso and arm strength. These ranged from more gentle Indian club exercises to weights and barbells. Of course, as the German gymnasts from Frederich Jahn forward had taught them, nothing toned the entire body like gymnastics.

Burnham favored the Swedish Movement Cure in his gymnasium, and as a consultant. This was a popular physical regimen invented by a Swedish physical therapist named Pehr Henrik Ling, in the early 19th century. His methods were later improved upon by another Swede, Johan Georg Mezner. The Swedish Movement was a combination of floor exercises, gymnastics and massage. The techniques of Swedish massage involved a precise knowledge of anatomy and physiology, and were designed to strengthen and build up the muscular structure of the body. The exercise and gymnastics were important, but the massage was of equal importance to the total health of the body.

Burnham began running the athletic program for the 23rd Regiment, Brooklyn’s most elite National Guard Unit. When he first started working with them, in the early 1880s, they were still located in the Clermont Avenue Armory. Burnham set up his gymnasium in the armory, with weekend classes for the soldiers and officers. He then set up similar gymnasia and programs in the 7th and 13th Regiments, as well. The facilities were open to the active men of the regiment, but also the retired veterans, as well.

Most well-to-do Brooklynites who remembered Avon C. Burnham met him in their schools. He was in charge of the physical fitness department at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, the city’s most exclusive boy’s school, for almost forty years. He established gym programs, including fencing there, and was an inspiration to his students He also set up the physical education departments at the Adelphi Academy and Packer Institute, both elite girls’ schools, and worked with them for ten or more years, as well. Unlike many educators who didn’t think girls needed the same education as boys, Burnham believed in physical education for females, both women and girls; a rare sense of equality for a late 19th century man.

He did open another gym in 1899, a “family gym,” set up in Columbia Hall, an assembly hall located on the corner of Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue, in Bedford. He also ran fund-raising gymnasium events in the armories, these geared towards children. He would set up equipment obstacle courses, and the children would have teams and run races across the equipment to capture the flag at the end of the course. He was also a fixture at some of Brooklyn’s largest churches, where he also set up exercise programs for the congregants. Some of Brooklyn’s most popular preachers were becoming “muscular Christians” under his tutelage.

In addition to this, he somehow found time to indulge in his theatrical side. For over forty years, Avon C. Burnham was a local celebrity on the lecture circuit. He gave dramatic readings, wrote and performed expository pieces, and acted in dramatic scenes from the classics. He also mixed music into his programs, with local musicians, singers and ensembles. To invite Mr. Burnham to your club or soiree was to be in for a complete treat. He hobnobbed with Brooklyn’s elite, and was comfortable in the parlors of the wealthy, and knew them all; men, women and children.

In 1910, now an elderly man, Avon C. Burnham had one more good deed in him. While on vacation at Lake Waramaug, in Connecticut, he was out boating when another boat capsized in the lake. A high wind had blown in, and the lake had gotten choppy. A boat carrying a young couple, a National Guard officer and his fiancé, as well as a female relative of the girl, rolled over when the young man lost his oar, and fell into the lake trying to recover it. His fiancé leaned over to help him, and capsized the boat. Sadly, they were found drowned in each other’s arms. The female relative would have drowned as well, but was rescued by Mr. Burnham, who had rowed frantically to the scene. He wasn’t in time to get the couple, but did rescue the woman. He wished he could have done more.

In 1913, Professor Burnham, as he was called, gave an interview to the Eagle. He was in his late 70s now, and had not slowed down. He had lost his beloved wife the year before, and he missed her. He was rattling around in his empty house, refusing to go live with his son, refusing to leave his memories. He was ever the dramatist, still spry and nimble on his feet, telling the reporter, “Life. Life. Life. Humanity. Humanity. What is it all, after all? Watch it on the street. Watch it in the cars. Watch it in the mirrors. Men used to fight like men in the jungle. They stood up straight, and they hit like men in the upper part of the body. What do they do now? They crawl upon their adversary; they come to victory or defeat crumpled like soiled napkins.”

Death must have snuck up on Avon C. Burnham, or he would have punched it in the face. He died in 1917 at the age of 80. He had finally moved to his son’s home in Flatbush. He had lived in Brooklyn for 77 of his 80 years, and had a huge influence upon the life of Brooklyn. Even though he catered to the upper classes, his programs for physical fitness found their way into the public schools and the YMCA and YWCA, and educated everyone. He taught that a sound body was incomplete without a sound cultural mind, and stressed both with missionary zeal. There should be a school, a gymnasium or a theater named after him, but he is now unknown and forgotten. Too bad, he was a true Renaissance man.

(Photo:Burnham’s Gymnasium on the corner of Schermerhorn and Smith, 1870. New York Historical Society.)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment