Walkabout: The Lords of Pigtown, Part 1

Read Part 2 of this story. Neighborhoods can get saddled with names because of location, like Brooklyn Heights, or Park Slope. They can get fancy acronyms like Dumbo or Soho, or they can be named after famous people or early residents, like Bensonhurst and Boerum Hill. Sometimes the names are reminders of far-away homelands, like…

Read Part 2 of this story.

Neighborhoods can get saddled with names because of location, like Brooklyn Heights, or Park Slope. They can get fancy acronyms like Dumbo or Soho, or they can be named after famous people or early residents, like Bensonhurst and Boerum Hill. Sometimes the names are reminders of far-away homelands, like New Utrecht, and sometimes the names just sound good and real estate-y, like Crown Heights. And then you get Pigtown. There was no attempt to prettify this name, it was derogatory, and everyone knew it. Yet like many derogatory names that are embraced in pride, they become a badge of honor of sorts. “I’m from Hell’s Kitchen, I’m from Crow Hill, I’m from Pigtown. You got a problem with that?”

Pigtown no longer exists as a neighborhood, but it was a real place. It was in Flatbush, which by the end of the 19th century was still a vast expanse of land, some of it being developed, some still farm or scrub land. The urbanization of Brooklyn began at the shorelines and moved inland, so the parts of Brooklyn that were in the center were among the last parts to see street grids, paved streets and sidewalks, utilities, and then homes and businesses. It seems amazing now, but as late as the 1930s, it was possible to still find shanties with goats in Brooklyn, on streets that also had row houses or small businesses.

Pigtown had a nicer name, Oaklands, but the name never stuck. As we travel around in Brooklyn today, the historic boundaries of Pigtown really aren’t all that remote, but for the late 1880s, they were at the edge of the city. Like many neighborhoods, the boundaries tend to be a bit flexible, but Pigtown basically went from its northern boundary of Malbone Street (now Empire Boulevard) to Midwood Street to the south. The eastern border was Albany Avenue, and Nostrand Avenue made up its western border. It could flex a bit this way and that. Today, that part of town is generally referred to as Wingate, next door to Prospect Lefferts Gardens and, technically, part of East Flatbush, with parts of Crown Heights South tossed in as well.

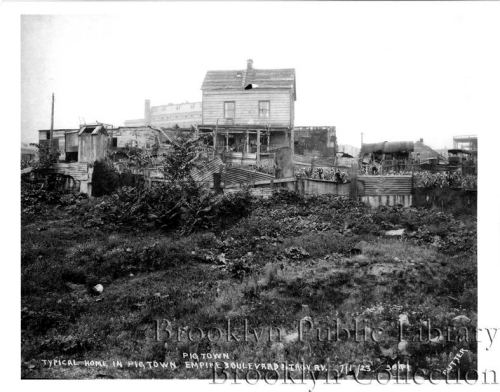

It was a pre-urban wasteland. It was where you took your wagonloads of ash waste, garbage, old furniture and junk and dumped them when no one was looking. Pictures of Pigtown show ash pits, dump sites and scrub brush facing lines of new buildings and empty dirt roads. Here and there an old shanty was still standing, and it was a neighborhood in transition, but one that no one had truly developed. It just grew. Goats, pigs and stray dogs roamed around, the pigs the last remnants of farms and livestock that had been pushed out of other parts of developing Brooklyn. Pigtown was no man’s land where the independent town of Flatbush brushed up against the city of Brooklyn.

Pigtown was poor and immigrant, home to some of Brooklyn’s poorest Irish and Italians. The Brooklyn Eagle, ever the barometer of the way good and decent upper middle class white people thought about their neighbors, was merciless in its depiction of poor Irish and Italians. Reporters would go to Pigtown and observe the living conditions and the way the people there lived. They would then condescendingly report on them, making fun of the accents, their culture, or the lack of sophistication. Pigtown was a fishbowl, always good for a feel-good story of how “those people” lived. And Pigtown gave them plenty of stories.

There was Thomas McCormick, “the Terror of Pigtown,” who had been arrested dozens of times for assaulting people, both men and women. McCormick had promised to kill any man, woman or child who testified against him, so his jail time on assault had been minimal. He did beat a policeman named John Derby practically to death, and served time for that offense. He was sent to the Crow Hill Pen several times for pickpocketing, and then he took some time to visit New Jersey, where he served seven years for robbery in the Trenton Penitentiary.

On March 25, 1896, he was arrested for an unprovoked assault on a man named John Divine. McCormick ran a seedy bar on East New York Avenue, and was standing in his doorway. Divine, who didn’t live in the neighborhood, had the bad luck of walking by when McCormick had the urge to punch someone. McCormick was arrested, and the police were overjoyed, because Divine was not afraid to testify against him. McCormick soon made bail, however, and was out five days later when he met someone else who was not afraid of him, either.

McCormick had gone to visit Michael Lynch, to patch up a disagreement. He found Lynch sitting in his home with his mother and sister, a baby in her lap, and Lynch offered McCormick a beer. McCormick soon got unruly, and Lynch ordered him to leave. When McCormick started a fight, Lynch pulled a revolver and again ordered him to leave. McCormick went out into the street; Lynch went back to his family. Suddenly, a huge rock came flying through the window, followed by others, one of which grazed the baby, while another broke the dishes on the wall. Lynch ran outside and tackled McCormick, and the two men tussled in the street.

McCormick was trying to bash Lynch’s head in with a rock, and in the struggle, Lynch shot him in the side. McCormick kept coming. Lynch shot him five times, and not until the fifth shot did McCormick pass out. Lynch calmly reloaded his gun and went into the house. By the time the police came, McCormick had been taken to the corner store and was lying on the table. He was taken by ambulance to nearby St. Mary’s Hospital. Michael Lynch surrendered, and McCormick regained consciousness long enough to accuse Lynch of shooting him.

The doctors thought they could probably save him, although he was seriously wounded. Thomas McCormick had been at death’s door before. When he beat Officer Derby, his fellow officers clubbed him in the head, and almost killed him. He had been stabbed three times, but it hardly slowed him down. One time, he went into a Flatbush barbershop and ate the barber’s live canaries, stuffing the poor birds whole into his mouth. The barber slashed him with his razor at seeing his beloved pets disappear into McCormick’s maw, but that didn’t stop him, either. McCormick had been shot twice in the hip, twice in the back, and once in the shoulder. In addition to that, he had head injuries from the fight.

In October of 1896, Michael Lynch went to trial for the attempted murder. He claimed self-defense, and testified that the fight had started when McCormick had made a pass at his married sister. Unfortunately, Lynch was no angel either, and had a long record, and had also been in prison several times. But in the end, Lynch was found not guilty. Thomas McCormick carried some of the bullets with him for the rest of his life. What happened to him in the end? I was not able to find out. I doubt he died of old age.

Next time: More stories of Pigtown. (Photo: Pigtown as late as 1923. Brooklyn Public Library)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment