Walkabout: The Jacob Dangler House on Willoughby Avenue, Part Two

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here. Read Part 1 of this story. The huge French Gothic Revival mansion on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand Avenues has always been a tantalizing mystery that I wanted to solve. Who built it? Who lived there, and what’s the story of the…

Photo by Suzanne Spellen

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here.

Read Part 1 of this story.

The huge French Gothic Revival mansion on the corner of Willoughby and Nostrand Avenues has always been a tantalizing mystery that I wanted to solve. Who built it? Who lived there, and what’s the story of the large mansion in an otherwise middle class area? Generally, row house neighborhoods grow up around large houses like these, but this time, the mansion was built much later. So much later that part of the neighborhood was being reclaimed by industrial use. This is not the usual pattern for wealthy people. Why build there, at that time? In Part One of this story, we found out that the house was built for Jacob Dangler, a successful meat packer and manufacturer of provisions; today we call his products cold cuts. He built the house for his family in a location that was only a short walk from his factory, and for him, that seemed to have made all the difference.

Dangler was born in 1851, and raised in a town in the Alsace-Lorraine, a western state in France that has been disputed territory for France and Germany for centuries. He came to America as a teenager, worked hard, saved his money, and was extremely successful. By the turn of the 20th century, he was more than able to afford to commission his dream house. Although culturally German, the French side of his upbringing seems to have come out in his choice of architecture.

He was also a very religious man, a devout Lutheran, so perhaps those traditional Gothic elements were very deliberately incorporated in this large French Gothic house. The architect of this structure remains unknown, pending physically digging through dusty records in the Department of Buildings, but it may have been Theobald Engelhardt, the premiere architect of the Eastern District, and the architect of many of Dangler’s other building projects. Whoever it was, they designed a large house worthy of any wealthy family. The Dangler family had been living nearby on Myrtle Avenue, but by 1902, this was their address when their names made the papers.

Unlike many other wealthy people, the Danglers were very low profile. One would expect, with a fine house like this, that there would be lots of parties, soirees and society events, showing off their wealth, but there weren’t. The press, especially the Brooklyn Eagle, frequently wrote articles about wealthy people’s homes, a pre-television version of “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” where florid descriptions of every room in the house accompanied a photograph or two, showing a world most of their readers could only dream of. But the Dangler family took no part in this sort of activity. I can’t blame them, but one hundred years later, these descriptions and photos are often the only record of what some of these houses looked like. We don’t have that here.

In 1903, two of the Dangler brothers got married in a double ceremony. Their choices of brides would warm the heart of any romantic. George Dangler married Louise Humbert, a young woman who had come over from Germany only four years before, and was employed as the housekeeper at the Dangler home. Emily Lohmeyer, the bride of Albert Dangler, was an orphan. She lived with her aunt on Lafayette Avenue and had met Albert while working as a cashier in Jacob Dangler’s store. Both girls were around 23, and were said to be quite pretty.

The wedding took place in Williamsburg at the Knapp Mansion, on Bedford Avenue at Ross Street. The happy couples were going on their honeymoons at Niagara Falls, and when they returned, George and Louise were going to live here at the mansion, while Albert and Emily were moving to 722 Myrtle Avenue, above the family store, where they had met. Today, that building is a health clinic, and has been extensively renovated from the factory/retail space it once was. The third Dangler brother, Henry, married the preacher’s daughter. His wife, Emma Julia Heischmann, was the daughter of Rev. Dr. John Heischmann, the long-time rector of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, located at Bedford and Dekalb avenues. Henry would go on to become a well-respected doctor.

Jacob Dangler had a very long life, filled by a busy career and a long association with his business, his later banking businesses and with his church. Like many wealthy and successful men, he was asked to be a trustee at a bank. He joined the board of the newly founded Fulton Savings Bank in 1903. Most of the trustees and officers in the bank were fellow German-Americans. In 1935, he became a second vice-president, and a year later, he was made first vice-president. He was on hand to open a new branch of the bank on Flatbush and Caton Avenues in 1931, and is in a photograph below. He’s No. 10 in the photograph, holding a portfolio.

He was very active in his church and other charitable activities. Jacob Dangler was president of St. Peter’s church board of trustees, and was also a trustee of the German Evangelical Home for the Aged and a member of the board of trustees of the Williamsburg Hospital, which he also helped found. He also was involved with the funding for Wagner College in Staten Island.

Dangler was obviously a workaholic. His business, which he ran with his son George, grew over the years, as well. He had problems with strikers in 1912, but in spite of that, he survived. His meat products, especially his bologna, were highly regarded and sold well to the growing number of delicatessens and food markets, as the eating habits of Americans changed in the 20th century, and sandwiches became an American necessity for working folks and school children alike.

A busy man needs an automobile, and in the early days of the car, Jacob Dangler shows up on the Automobile Club’s book of registered car owners in New York City. In 1916, his chauffeur, 22 year old Harold Benson, was arrested for felonious assault and reckless driving. He hit a six year old girl on Willoughby Avenue, fracturing her leg. The papers did not mention if anyone else was in the car at the time. The girl was taken to Cumberland Hospital and treated.

Albert Dangler, the son who lived above the store, rescued an entire household of people from a building nearby. The building was owned by his father, who had a lot of real estate in the neighborhood. He was in the building and smelled gas, and broke into an apartment where everyone had succumbed to the fumes. He was able to turn off the gas and get everyone out. They were revived and taken to the hospital. Albert saved the lives of six people.

In 1911, Albert left his father’s business and set up his own business in the Sunset Park area. His business also packed and produced pork and other meat products. He was not as successful as his father, but he did well. Unfortunately, he was never in great health, and died well before the other members of the family. His mother, Josephine, died in 1929, after a long illness.

Jacob Dangler died in 1939, at the age of 87. He had been sick for only a few weeks. Up until that time, he had carried on his usual routine, getting up at 5 am in the morning, and walking over to 722 Myrtle Avenue to his business to conduct a full day’s work. He never retired. The funeral was held at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, and he joined his wife and son in Green-wood Cemetery. He left behind his other two sons, their wives, eight grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

The house went to George and his wife, who had been living there since they had gotten married. Dr. Henry and his family now lived in suburban Flatbush. The neighborhood had long since changed from when the Danglers built the house, and they were now surrounded by factories and an economically and racially changing neighborhood. Most of the long established Christian German families were long gone, their mansions now home to wealthy German Jewish families.

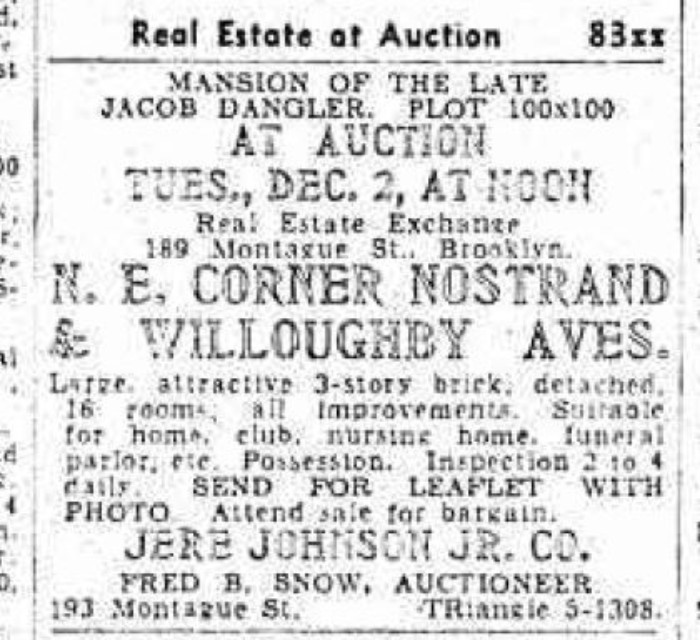

Down on this end of Willoughby, the neighborhood was becoming ethnically diverse, with Jewish, black, Irish and other families moving into the brownstones. Nostrand Avenue had become a noisy and busy vehicular roadway. Two years later, in 1941, the house was put on the market. A large ad was placed in the papers, touting the house as an ideal location for a home, club, nursing home, school or funeral parlor.

I don’t know who bought the mansion at that time, but 26 years later, in 1967, the building was purchased by the Oriental Grand Chapter of the Eastern Star, a masonic organization founded in 1850, for both men and women, although now it is almost exclusively for women. Orders of the Eastern Star are usually founded in conjunction with a male Masonic counterpart. The Order has owned the house ever since.

Over the years, the house underwent many changes. Walls were taken down and the house expanded into large rooms for meetings and parties. A reader related in the comments from part one that he had been in the house, and large rooms take up the entire ground floor. An extension was built on the back, further expanding the public space. From advertisements on the Internet, it seems that several Masonic lodges and other organizations use the space. The Dangler family was the only family to ever live here, by all accounts. Totally forgotten today, they left behind only a large mysterious mansion on a busy corner of Bedford Stuyvesant, a monument to success and hard work. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment