Walkabout: The Gold Street Explosion, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. On the morning of November 20th, 1908, hell opened wide its gates onto Gold Street, between York and Front Streets, in what is now DUMBO. Workmen were working on a huge sewer project, which involved digging a four story deep trench through the street. Although they had tried to…

Read Part 1 of this story.

On the morning of November 20th, 1908, hell opened wide its gates onto Gold Street, between York and Front Streets, in what is now DUMBO. Workmen were working on a huge sewer project, which involved digging a four story deep trench through the street. Although they had tried to raise and isolate the large gas main that had been buried underneath the surface, there appeared to have been a leak, which resulted in a huge explosion that shattered the lives of the people in this working class neighborhood.

For more background, please see Part One of the story. The horrific explosion took the lives of men, women and children; workmen and pedestrians; Good Samaritans and unfortunate passers-by alike. What resulted were great heroism, dumb luck, great stupidity, cover-ups, accusations and then public amnesia. The usual tale of a disaster of this proportion here in Brooklyn.

After the explosion, Gold Street was an inferno. The sides of the fifty foot trench dug for the massive sewer pipe collapsed, taking workmen and pedestrians with it, crushing them under tons of dirt, water, rocks and timber. The broker water main made things worse, spilling thousands of gallons of water into the trench, making it hard to find victims, and turning the bottom of the morass into a lake of quicksand. On top of that, the explosion had shattered the gas main, turning it into a giant flame thrower which ignited anything flammable, especially the timbers used to shore up the sides of the tunnel.

Soon after the explosion, the first policemen reached the scene. They quickly called headquarters asking for more men, firemen and ambulances. These first responders were quickly overwhelmed, but soon had help from at least six precincts from all over the surrounding area. The Deputy Commanders of both the police and fire departments were soon on scene, as were the Superintendent of the Buildings Department and the Chief Engineer of the Sewer Bureau. Also on the scene were growing numbers of onlookers who had to be kept away from the area for their own safety, as well as to allow the rescuers and workers in to help people.

They couldn’t try to rescue anyone who might be buried, as the fires were keeping them away from the trench, so the first job was to put out the timber fires, and get people out of the nearby houses and tenements, many of which had been severely weakened by the force of the explosion and the shifting ground. Most of the people in the houses had fled, but police had to break down the door of one tenement apartment to rescue a woman who had barricaded the door on a top floor apartment. She and her two children were rescued.

A local parochial school full of children rushed to get their children out of the building, adding hundreds of children in the streets, but their teachers managed to march them out in fire drill formation, to safety. Now that the children and the neighbors were safe, and the fires were being put out, it was time to see if anyone else was alive. It was thought that at least 50 workers were buried, but later many turned up safely.

Unfortunately, this situation was top heavy on Commissioners and officials in charge, and chaos was in order, with various officials each trying to take command, often contradicting each other, resulting in hours in which absolutely nothing happened. The Deputy Water Commissioner managed to get the water shut off, and someone contacted the gas company, which shut off that main, but the chiefs were still debating who was in charge. Finally, the mayor, George McClellan, Jr., arrived on the scene and took over.

McClellan was the son of the famously failed Civil War general of the same name, and was a Tammany Hall operative who became mayor in 1904. He would be voted out of office a year later, but this day the mayor must have taken lessons from his father on commanding the troops, because he drove over the bridge in his official car and made order out of chaos, putting the agencies and head honchos in line, giving them each an area of responsibility, while he coordinated their efforts.

Mayor McClellan actually had to write a letter authorizing the different agencies to allow the Health Department, which was in charge of finding bodies, to take charge. Up until he showed up at the scene, the Police Commissioner was not letting the Buildings Commissioner or his men onto the scene, and time was wasted while they stood on the sidewalk arguing with each other. It was disgraceful.

By the evening, workmen and rescuers were shoring up the sides of the trench, stabilizing it so that debris could be removed and bodies collected. They did not expect to find any survivors below the surface. Large electric lights were strung across the scene and gasoline torches were lit to allow workmen to shore up and dig all night. Men also worked to shore up some of the houses still standing, but in danger of collapse.

A few miracles did occur. One of the sewers workers had the foresight to check on the nearby manholes, thinking that some of the missing workers may have made it into the sewers, but were now trapped underground. When he opened the manholes, four workers came up out of the ground. They had been close enough to the finished part of the tunnel to run through it, escaping the collapse but chased by the rushing torrent of water running through the same tunnel. Guided by light coming from the manholes in the street, they were able to run close to the river and to safety.

Some of the first casualties were a woman and three children who were walking down the street when the explosion happened. The sidewalk collapsed under their feet, and they disappeared into the pit. A neighbor, blacksmith Samuel Abrams, tried to reach them, but was himself felled by falling timbers. All were lost. Further down the street, another little girl seemed to have suffered the same fate, but she was rescued thanks to the bravery of one of her friends. Little Agnes McNanara, only six years old, was headed to the store for her mother. She stopped at a friend’s house, the home of seven year old Kate Curry, and the two children headed to the corner store.

When the explosion occurred, both girls found themselves falling, as the ground disappeared beneath them. They were clinging to the dirt at the edge of the pit, slowly slipping away. All of a sudden, Margaret Hickey, an older child, who was in Kate Curry’s house at the time of the explosion, looked out the window, and saw the girls go down. She rushed outside, lay flat on her stomach, and was able to grab the Curry girl easily, and pull her up. The McNanara child was further down the trench, but Margaret was able to grab her as well, almost falling in herself, and pull her up to safety. Poor Agnes McNanara was so traumatized that she didn’t go home, and wandered the streets until nine that night, when someone found her and took her home.

Modern technology came into play here, the first time for a major Brooklyn disaster. The Brooklyn Union Gas company had their telephone operators call all of their customers in the affected area to tell them to turn their gas off until the main could be fixed. Over sixty extra telephone girls were called in from all over the borough to make the calls. The operators were able to reach 10,000 customers directly through their emergency lines, and they figured they reached another 3,000 through word of mouth. This move may have prevented even more fires and gas mishaps in the Gold Street area.

Of course, in a situation like this, blame must be placed, and the nearest scapegoats were the construction company that was digging the trench and laying the sewer, and the gas company. The police came in and arrested Peter McEvoy, the site foreman for Brooklyn Union Gas, and John J. Haggerty, principal of the firm Haggerty & Rogers, the contractors. The police found McEvoy at the disaster, working with his men to get the gas shut off, and they hauled him off right then, stupidly delaying the shut off. The president of Brooklyn Union Gas, General James B. Jourdan, was outraged. He insisted that the gas company had not been negligent, and that arresting McEvoy while he was in the process of getting the gas turned off was beyond irresponsible.

Arresting Haggerty was also questionable. The charges alleged that his firm had not taken the proper steps to protect their workmen. Haggerty vehemently denied this, and Chief Engineer Griffin of the Sewer Department, who was at the scene, backed Haggerty. Both men were held at the Adams Street Courthouse, and were released on $2,000 bail each.

The aftermath of the disaster is rather murky. Follow-ups by the press were few. A week later, the final death toll and the conditions of Gold Street were finally known. Twenty people lost their lives. Twelve of them were workmen, including Fred Schiffmeyer, the Borough Inspector of Sewers, who had been inspecting the site at the time of the explosion. The other eight people killed were passersby and residents of the block, including at least two women, several children and the Good Samaritan, Samuel Abrams, who had tried to save lives, and lost his in the process. Fifteen buildings on Gold Street were severely damaged and were being shored up.

As far as I could tell, no one was ever charged in the tragedy, it was deemed another one of those accidents where a perfect storm of smaller events led to a larger disaster. Either that or a massive cover-up took place. The press just seemed to let the incident die away. From all indications, Mayor McClellan was also a hero here. His commissioners, especially the Police Commissioner, were more concerned with who was in charge, rather than with coping with the disaster, and valuable time and manpower was wasted until the Mayor showed up and took charge. Hopefully, this incident would result in some of the protocols now in place for responses to disasters.

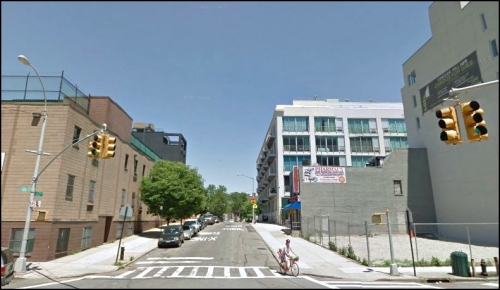

Today, this block of Gold has been developed as housing, most of it new luxury loft type housing, combined with a couple of buildings left over from the mid-20th century urban renewal, and a vacant lot or two, waiting for development. Subsidized housing projects begin the next block. The neighborhood of wood framed houses, businesses and tenements is long gone. Only one older building, housing a pharmacy, remains on the block, the only reminder of this block’s 19th century residential past. You would have to dig fifty feet down, where the 1908 sewer that cost so many lives still lies to find anything left of the Gold Street Disaster. GMAP

Photo above: Early 20th century surface construction methods, this for the subway. Audobonparkny.org.

Disgraceful? Really? What’s WRONG with you?