Walkabout: The Gold Street Explosion, Part 1

Read Part 2 of this story. You know those sequences in movies and documentaries where the camera stays stationary while the world changes around it in seasons, years or centuries? A seed germinates, grows, blossoms and then dies, or buildings and cultures rise and fall over centuries? A look at the area of Brooklyn we…

Read Part 2 of this story.

You know those sequences in movies and documentaries where the camera stays stationary while the world changes around it in seasons, years or centuries? A seed germinates, grows, blossoms and then dies, or buildings and cultures rise and fall over centuries? A look at the area of Brooklyn we now call DUMBO would be a fascinating study for such a time sequence.

The shoreline that the Canarsee people fished from would become a Dutch outpost, a settlement, and then the growing village of Breukelen. That town would grow, and the same area that once held clapboard houses, one-story shops and taverns, stables and businesses, would grow to include brick homes, large commercial warehouses and offices for the import and export of goods, and other businesses and crafts tailoring themselves to the shipping manufacturing industries that hugged the East River and New York Bay. The village of Brooklyn had become a town, and that town would become a city.

By the end of the 19th century, most of the DUMBO area was already factories and warehouses. But just outside of the warehouse district at Fulton Landing, the neighborhood of Vinegar Hill and parts of Fort Greene, Downtown Brooklyn, and the lower part of Brooklyn Heights were teeming with people.

With the exception of the few remaining blocks of Vinegar Hill, and one or two blocks of Fort Greene/Downtown, under the Manhattan Bridge, these residential neighborhoods are gone without a trace, lost to roadways, on and off-ramps, factories, Jehovah’s Witness buildings, and housing projects. But one hundred years ago, these neighborhoods housed the working class and the poor, many of whom worked in the nearby factories, the waterfront, or the Navy Yard.

They were largely Irish, but this large neighborhood also was the center of Brooklyn’s African-American community, closer to Downtown, and also had a sizable population of Eastern European Jews, Italians, Norwegians, Swedes and other recent European immigrants. Much of the housing stock consisted of wood frame tenement buildings, interspersed with small frame houses, modest row houses, stables, taverns, churches, stores and other buildings. Brick buildings were, by law, replacing the wood frame tenements, but really, no one really paid much attention to what went on here.

By the first decade of the 20th century, factories shared streets with homes, as companies like Benjamin Moore Paints, Durkees, Squibb and the Brooklyn Gas Light Company, soon to be part of Brooklyn Union Gas, along with many other industries, vied for space among the houses and tenements. It was a busy and crowded neighborhood in the changing days of the early 20th century. Electricity was in many homes, along with gas, and the telephone was no longer a curiosity. Automobiles were joining horse-drawn carts and electric trolley cars on the streets of Brooklyn, and the city, a part of Greater New York City for ten years now, was still growing. And so we come to our story.

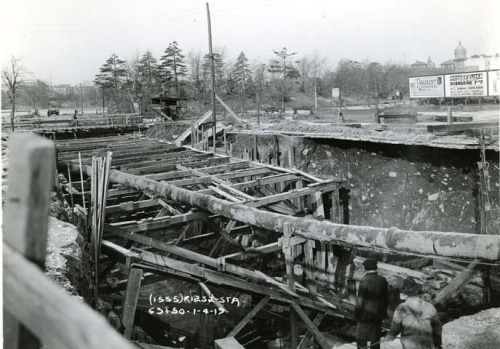

On November 20th, 1908, Gold Street, between York and Front Streets was all torn up, as a deep trench was being excavated for a new sewer pipe. The trench was fifty feet deep and thirty feet wide, a huge pit designed to hold a new sewer pipe measuring thirteen feet, six inches in diameter. This was before the invention of a lot heavy excavating equipment, so this trench had mostly been dug by large crews of men the old fashioned way: with picks and shovels, with the help of some machinery.

The sides of a pit this deep couldn’t stand by themselves, so they were shored up by a continuous sheathing of heavy wood beams and planks, which formed a retaining wall on both sides of the street. The entire street had been excavated, with only enough sidewalks left for pedestrians to just squeeze by. Only a few feet from the sidewalk and trench were tenements, stores and homes.

The workers had taken care to excavate the large underground gas line that supplied gas to every home and business on the block, and the sixteen inch mains were lifted above the trench, and laid on the surface. The two foot water main was also a concern, and they had to dig around it, as well. It, of course, could not be lifted.

The massive new sewer pipe itself was cast in concrete, in sections, and rested on a brick liner where the parts would be joined, and on this morning of November 20th, the crew was reaching the completion of this stage of the project, and all was well. After the concrete and brick sections were placed and connected, the trench would be carefully filled in, the gas and water lines reburied underneath the street, and the retaining walls removed. It was still a huge project, with much to do, and winter was fast approaching.

Prior to that day, reports would say, the workers and the neighborhood people had complained for a week that they could smell gas. But those complaints were ignored, or dismissed in the rush to complete the project. The contractors themselves said that gas was gathering near the gas pipes and behind the wooden walls of the trench.

But no one did anything about it and inspections turned up no discernible leaks. As the men worked that morning, all of a sudden, there was a deep, dull explosion, like an earthquake had just occurred below the surface. Time stopped, and in that moment, the entire trench exploded upwards, sending broken concrete pipe, bricks, wood, sand, water, and dirt flying high into the air, raining death and destruction down on Gold Street.

The fifty foot deep trench collapsed on both sides, burying workmen beneath the falling rubble. The water main cracked open, spilling tons of water into the filling trench, creating a river of debris and mud, which soon became like quicksand. The gas main on the surface also cracked open, and the gas ignited, shooting out like a giant flamethrower, setting anything flammable on fire. Tons of earth, machinery, timber and wreckage spilled into the deep pit, as deep as a four story brownstone building. The narrow sidewalks also disappeared into the abyss. Death was literally at the door for the people of Gold Street.

Eye witnesses said that a woman and three children who were walking down the street, disappeared into the pit, along with the sidewalk they were walking on. A man named Samuel Abrams, who lived at Front and Gold Street, tried to save them, but he was buried by a pile of blazing falling timbers that struck him down in the middle of the block. Stunned eyewitnesses couldn’t get through the flames to save him, or the woman and children. P

eople living in the tenements rushed to their front doors to find they had no sidewalks and their first and last steps outside would be into hell. They turned around and ran to the back of their buildings and ran for their lives. Only the bravest went back into their apartments to grab valuables and possessions before making their way out of the buildings. By the time the police and rescue workers got to the scene, countless people were dead, dying, or missing; men, women, and children. It was a disastrous tragedy of epic proportions. GMAP

Next time: The conclusion – heroes, scapegoats, the dead and the miraculous survivors. The cause and effect of The Gold Street Explosion of 1908, next time.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment