Walkabout: The Colonel of the 47th Regiment, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. Colonel Edward F. Gaylor was the commander of the 47th Regiment, one of the many National Guard units stationed in Brooklyn during the second half of the 19th century. The 47th was located on Marcy Avenue in Williamsburg, a new headquarters completed in 1884. The design and construction of…

Read Part 1 of this story.

Colonel Edward F. Gaylor was the commander of the 47th Regiment, one of the many National Guard units stationed in Brooklyn during the second half of the 19th century. The 47th was located on Marcy Avenue in Williamsburg, a new headquarters completed in 1884.

The design and construction of the armory was the topic of much scrutiny and anticipation, and surely no one was more able to completely appreciate the complexity and nuance of building than Edward Gaylor, as he was not just a military man, he was also an experienced architect and the son and brother of architects.

As we learned in Part One of this story, Edward Gaylor was the son of William Gaylor, a prominent Brooklyn architect based in Williamsburg, who was responsible for many important Brooklyn buildings, and was appointed the Commissioner of Buildings under Mayor Seth Low’s administration.

William was in partnership with both of his sons, Edward and John, and Edward’s name appears on many buildings in the Eastern District as parts of Williamsburg, Bushwick and northeastern Bedford Stuyvesant were known. But Edward’s passion was the military, not architecture, so he joined the National Guard and the 47th Regiment at the age of 20.

In the space of only a few years he had risen through the ranks and was made commander of the regiment in 1884, a prestigious position that he took up gladly and with a great deal of pride and overbearing arrogance. He was a harsh commander who was not loved by his troops, and he wouldn’t allow anyone to get credit for anything except himself.

After a couple of very public encounters, where he loudly expressed these opinions and which were eagerly picked up by the press, all of Brooklyn knew that Colonel Gaylor was a right, proper jerk. But that’s no reason to take someone’s command, so unpopular or not, Colonel Gaylor remained commander of the 47th well past these revelations.

But by 1889 the general attitude of this once-famed regiment was starting to suffer. It started at the regiment’s annual training camp in Peekskill where a corporal punched out a private over the use of a tin plate, tossing in an anti-Semitic slur while he was at it, as Private Abram Sanders was Jewish. The private was twice the age of the corporal and half the size, and he was hit in the lip so hard that it needed medical attention.

The company’s first medical officer, Surgeon Ashwin, saw the cut, dismissed it as minor and walked away. His fellow doctor, Assistant Surgeon Jeffreys disagreed, and immediately treated the wound, sewing the lip back together, which was later diagnosed as saving the private from a permanent disfiguring injury.

That night the two doctors got in a fight over the incident. Surgeon Ashwin accused his subordinate of going behind his back to treat his patient. They had to be separated from each other and ill feelings overshadowed the rest of the company’s exercises.

When they got back to Brooklyn Assistant Surgeon Jeffreys sent Colonel Gaylor his letter of resignation. Colonel Gaylor had the corporal temporarily reduced in rank, and the private in the incident, Abram Sanders, left the Guard when his term of service was over. The camaraderie of the unit was suffering greatly.

In May of 1890 Colonel Gaylor took a three month leave of absence to work on an architectural project in New Jersey. Command went to Lt. Colonel John Eddy. That month a long, full page article was printed in the Eagle, with the names, pictures and bios of all of the Guard commanders in Brooklyn.

In this article, Colonel Gaylor was praised for the tight ship he ran as well as the success of his unit in military exercises, their skills and polish. Although Gaylor was only ten years old when the older Civil War commanders cut their teeth in battle, he was praised for his military acumen and success. That was soon to change in a heartbeat.

The next headline the Colonel was featured in was about his arrest. The police had come to the armory and placed the Colonel under arrest for mismanagement of the estate of Richard Demille, and defrauding the beneficiaries, Jennie and Julia Beckett. Gaylor was trustee of the estate, and was charged with managing close to $6,000 for the beneficiaries, who never received a cent.

That was in October of 1890, by November, the paper announced that he had resigned his command. That January, with the headline of the paper declaring, “Gaylor is out,” the Colonel performed his last official act, leading his men at a dress parade and review at the armory, and event that was attended by the mayor, and other dignitaries and military brass.

The once proud colonel’s life was a mess. The details get a little convoluted and messy, but here’s the gist of it. While he may have made the 47th’s marching line the envy of Brooklyn’s Guard units, Gaylor was unable to manage his outside businesses and get them in line. A successful architect, he was not a very successful real estate developer. His first project did well, netting him $14,000, but his next project, a block wide development in Williamsburg, was a failure, resulting in foreclosure and the loss of $54,000.

In 1890, after the arrest, the following announcement was made in the NY Herald: “Colonel Edward F. Gaylor, of Brooklyn, has gone into temporary retirement owing to financial entanglements.” That was an understatement. When his Williamsburg project tanked, the Colonel borrowed from the Demille estate, and didn’t have the money to pay it back.

Amazingly the case would be thrown out of court because the police arrested the Colonel while he was on official military duty, he was discharged on a writ of habeas corpus. He must have thought he had gotten his mojo back, but a year later, he was back in jail.

This time, it was family and personal. The Colonel was married to Mary Watts, the daughter of a wealthy banker named Simeon Watts. The Colonel was made the executor of Simeon Watts’ estate, and after the old man died at his summer estate in Lewisboro, in Westchester, Gaylor had the keys to the family purse.

Apparently he couldn’t help but “borrow” from that one as well. In 1890, the same year of the Demille case, the heirs and beneficiaries of Simeon Watts wanted an accounting of the estate, and were not happy with what they found, because at least $10,000 was missing.

The colonel was busy with his foreclosures, the Demille case and his dying military career, and he ignored the Watts relatives who had demanded an accounting. A year later, a warrant was issued for his arrest on a charge of contempt of court.

He managed to avoid getting arrested, and had finally given an accounting to a White Plains judge, placing in the judge’s hands an $8,000 mortgage on his Westchester farm, and a promissory note for $3,000. That didn’t do it for the heirs, but the Colonel remain elusive and free until his neighbor, who had the adjoining farm in Katonah, was deputized, and was able to go next door and arrest him.

That farmer, Charles Webster, was charged with bringing his man into the White Plains sheriff’s office. But Edward Gaylor was a friend and neighbor, so in the spirit of cooperation, the two men decided to stop off for a drink at the local pub before getting the train to White Plains. When they got off the train, the Colonel offered to buy Webster another drink, which he accepted, and they ended up going to several establishments on their way to the county sheriff.

By this time, Charles Webster was sloppy drunk. Gaylor told him that he wanted to go to a lawyer’s office to retain counsel, so they went to the offices of a local attorney. As soon as Webster sat down in the reception room, he fell asleep. Colonel Gaylor walked out of the office, walked to the train station and got on a train bound for Brooklyn.

Charles Webster woke up in time to realize his prisoner was gone, and he headed to the train station. A real deputy had gone looking for the both of them, and caught Webster as he was boarding the train. He was arrested to aiding a prisoner escape. It was thought money had exchanged hands.

Colonel Gaylor was seen in Brooklyn, in several liquor stores, with friends. His luck finally ran out, and he was arrested and brought back to White Plains. He appealed to his father, who told the papers he was done with his son, who had brought his own troubles upon himself. He was not going to help.

From what I could tell, the Colonel dodged another bullet on this one, too. He did little jail time, and probably lost the farm to pay off his debts. The papers are very unclear here. But his troubles were not over. By 1893, he and his brother and both of their wives, along with two others were all defendants in a law suit over three large plots of land in the Eastern District. I don’t know how that one turned out, but it seems that the Colonel had developed a serious drinking problem to add to all of his others.

In February of 1894, he was arrested for public intoxication on Fulton Street and Albany Avenue. He was picked up and spent the night in jail. The next day, he cleaned himself up, and with his old military bearing, appeared before Justice Connolly, who recognized him.

He pleaded guilty, and was released. This was the second arrest for public drunkenness for the Colonel. His sentence had been suspended that time, as well. In that case, a year before, he had been picked up after being found passed out in the street at Quincy and Throop. No one recognized him that time, and he had caused quite a scene, demanding that an ex-officer of the National Guard should be released. He was, after the judge in that case also recognized him, and had known him in his prime.

He was now living at 321 Decatur Street, in Bedford, the object of much pity, and probably quite a bit of schadenfreude on the part of his old military enemies and critics. There had been another arrest in Bridgeport, Ct, this one resulting in a jail sentence, and his financial situation was still a mess.

Gaylor was still practicing architecture in 1894; it was his rather odd and disconcerting design of an apartment building on Decatur Street that introduced me to him initially. His father died in 1895, it is unknown if they had reconciled. Perhaps he was able to provide for his long suffering wife and family by returning to the field of architecture.

Articles in the Eagle and other local papers well after his forced retirement paint Colonel Gaylor as a stern disciplinarian who was an otherwise excellent commander. No mention of his problems with his massive ego, or his unpopular stance with his men appears.

The Colonel would probably be happy to know that he was well remembered in that regard. He died in 1914, and is buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery. His funeral with was full military honors and much pomp and circumstance. Many of his buildings also survive him to this day. He would have liked that, too.

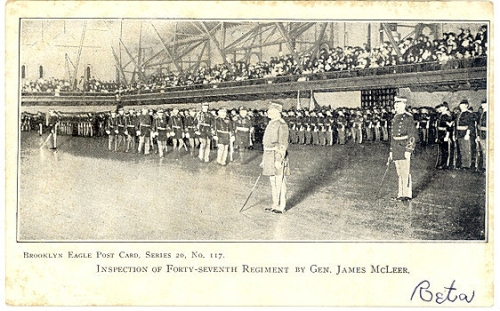

(Postcard of 47th Regiment, around 1894, after Gaylor’s resignation)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment