Walkabout: The Coignet Building – What’s the Big Deal?

With the opening of Whole Foods this week, the condition and fate of the Coignet building has been in the news a lot. To many, it’s just another wreck of an old building that should be torn down. But for preservationists, and architectural historians, this “wreck” is an important building. It stands there, forlorn and…

With the opening of Whole Foods this week, the condition and fate of the Coignet building has been in the news a lot. To many, it’s just another wreck of an old building that should be torn down. But for preservationists, and architectural historians, this “wreck” is an important building. It stands there, forlorn and neglected, but it’s truly worthy of restoration and reuse. Not only for what it is, architecturally speaking, but for its place in Brooklyn’s history. Here’s the story of the Coignet building.

Today, where even the cheapest infill housing is now made of reinforced concrete, a concrete building seems like no big deal. But the Coignet building was one the first of its kind in the United States. Concrete is one of civilization’s oldest building materials, a mixture of sand or gravel, water and a cement binder. The ancient Romans used it to build vaulted roofs, ceilings and their great domes. The Pantheon in Rome, built in the 1st century, has the largest un-reinforced concrete dome in the world, and it’s still standing firm after over two thousand years. Concrete is strong, and lasting, and cheap.

But for centuries, the Western world has gone with other materials, specifically brick, wood and stone. In the mid-19th century, European builders began exploring the use of concrete again, at the same time experimenting with adding iron for reinforcement. One of these men, Frenchman Francois Coignet, was especially successful. His patented formulas and the practical uses of his concrete at the 1855 Paris Exhibition gained him great attention, even here in America.

After the Civil War, Brooklyn and the rest of the industrialized North was undergoing a massive building boom. Wood had been replaced by brick and stone, but the search was on for newer and better building materials. Terra cotta and cast iron could mimic and replace stone for facades. Both were lighter in weight, could be tailored for specifics much easier and cheaper than stone, and they were fire retardant. The use of both materials allowed for a more rapid build, and, in those days before reinforced steel infrastructures, allowed for taller and larger buildings.

Oddly enough, concrete was still not popular. Around 10 years after Francois Coignet’s success at the Paris Exhibition, two Brooklyn businessmen travelled to France to meet with Coignet. Quincy Adams Gilmore was a structural engineer. A West Point graduate, he had risen to the rank of general during the Civil War. Through his military studies, he had become fascinated by fortifications and building materials, and had researched Coignet’s processes, and had even written a paper on them.

His companion was a Brooklyn Heights doctor named John C. Goodridge, Jr. He too was fascinated by the possibilities of concrete construction, and would end up writing most of the publications for their new company, and securing patents for concrete manufacturing. He would end up becoming president of Brooklyn’s first concrete company. They, and two other men, would make up the officers of the new Coignet Agglomerate Company of the United States, founded in 1869.

They would specialize in what was called “cast” or “artificial stone.” Through the use of molds, not carving tools, they fabricated building elements that were much cheaper than cut and carved stone, but were practically indistinguishable from stone. Coignet sent over trained staff from France to teach the Brooklyn management and workers the Coignet patented techniques for manufacturing. The first factory was in what is now Carroll Gardens, and was on the corner of Smith and Hamilton streets, taking up 16 lots.

The factory made all kinds of concrete building elements, but specialized in stone blocks, both large and small. They even manufactured a “Beton Coignet brown-stone” which was superior in all ways to natural brownstone. By 1871, the company could boast that they could manufacture the front of an ordinary house in a day. They were growing in business and popularity, and would need to expand their factory soon. They decided to move to Gowanus, to a large manufacturing space they would build on 3rd Avenue.

The new factory would expand from 3rd to 6th streets, and was begun in 1872. The manufacturing facility was a huge wooden shed that covered an acre, and could manufacture the fronts of ten houses a day, in addition to all of the other decorative elements they also made. Their stocklist included columns, blocks, keystones, window tracery, and urns. The factory was in the perfect place, right on the Gowanus Canal, accessed by the new Fourth Street branch of the canal. Good could be shipped and materials received right at their door.

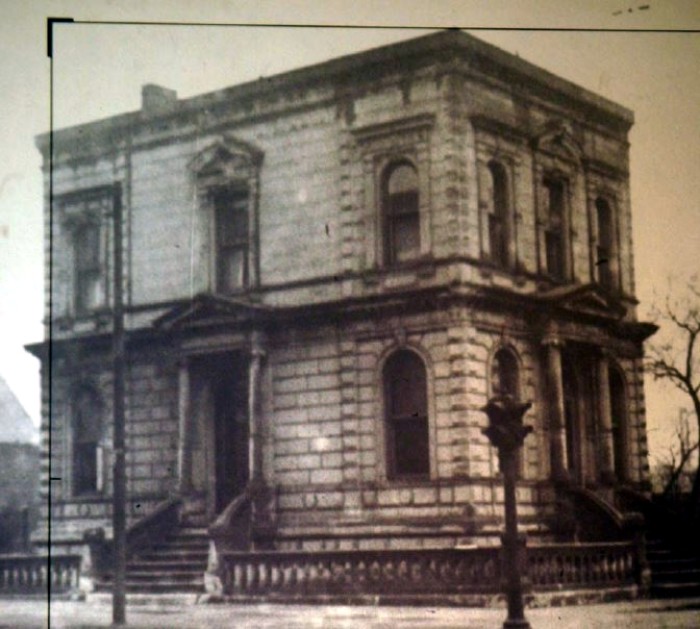

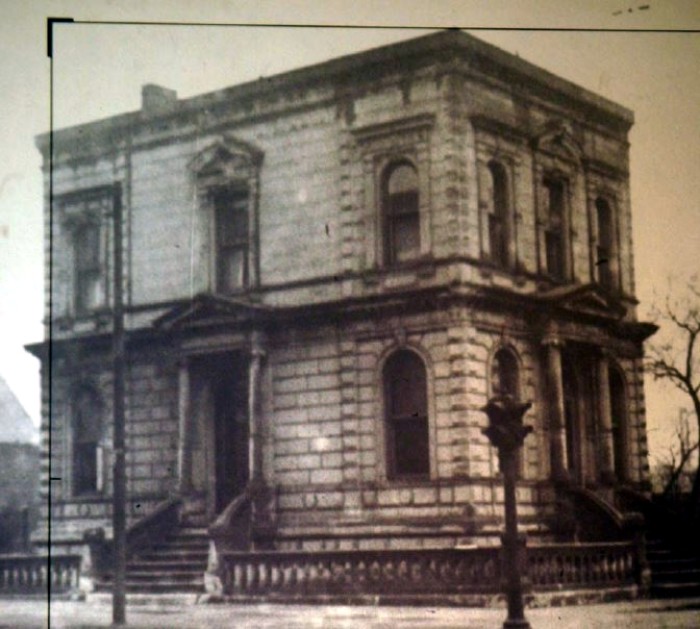

The company had changed its name to the NY and LI Coignet Stone Company, and by 1872, this building was just about finished. It was designed to be the company office and showroom. Here, potential customers could see how the Coignet products could be used in an everyday, practical building. At least two different kinds of concrete were used in its construction. The body of the office was made of concrete blocks, using molds that could be made in any shape or size. After being cast, the blocks were cured outside for several months.

The foundation, which widened as it reached the ground, was built to support the load of the concrete above. It was called monolithic concrete, and was made by building forms and pouring the concrete in stages, packing it down densely, and then pouring more, building the foundation up in layers until it reached the desired height. The original floors were also concrete, reinforced with iron scraps, or an iron framework. Finally, all of the ornamental features of the building; the columns, porticos, windows and doorways, were all cast concrete elements, cast in molds that could also be customized, as per a client’s needs.

The blocks that made up the building were tinted and treated to resemble grayish-white granite. Other stone treatments were, of course, available, such as marble, brownstone and limestone. Unfortunately for us today, the original “granite” blocks are not visible, as the entire building was faced in red brick veneer in the 1960s. That brick is NOT the original Coignet building, and when this building is restored, that will be gone, and the original revealed again.

Beton Coignet, as the product was called, was used in some of New York City’s most famous and important buildings. The arches and clerestory windows in James Renwick’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral are Beton Coignet. So too is the Cleft Ridge Span, one of the great bridges in Prospect Park, notable also for its tinted ornamental details. This was one of Calvert Vaux’s designs, and he also used Beton Coignet in his original buildings for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and his American Museum of Natural History. Today, both buildings are still in the complex, although they have been surrounded by later additions. There’s even a Coignet concrete tomb in Evergreen Cemetery, in Queens, designed in 1873.

The architect of record for this building is William Field and Son. Field, whose offices were in Manhattan, is best known for his landmarked tenement buildings for philanthropist Alfred Tredway White. He designed Cobble Hill’s Home and Tower Apartments, as well as the Riverside Apartments in Brooklyn Heights. Earlier in his career, in the 1850s, he and his then partner John Correja, Jr., were responsible for many of the cast-iron building in SoHo. The use of new materials and technology was not foreign to him. His actual design of the Coignet building has been determined to have been pretty minimal, they knew what they wanted their building to do and represent. Architectural historians surmise that Field and the Coignet team just picked from their catalog of products and went next door to the factory and got it.

Unfortunately, Coignet stone had a very short run of popularity. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1873, and auctioned off its patents in 1876. John Goodridge never gave up on concrete, or his methods. He reorganized the company in 1877 as the New York Stone Contracting Company, and sent out press releases announcing that he had improved on the original Coignet methods, and his new product was cheaper than before, as well as better. But in spite of that, the demand for their decorative elements declined, and the company began making reinforced concrete forms for non-residential purposes, such as the lining of tunnels, and the repairs of piers and abutments. Goodridge patented a method of laying concrete underwater, and by the 1880s, most of the company’s business was outside of New York City, most of it upstate, such as a bridge over the Niagara River and work for the Erie Railroad.

The land the factory sat on was leased from Edwin Litchfield’s Brooklyn Improvement Company. Litchfield, whose villa still stands in Prospect Park, owned much of what is now Park Slope and Gowanus. Third Street, which began at his house, was his personal road down to the Gowanus piers, which he also owned. He had made his money as the president and treasurer of the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railroads. It was Litchfield who drained the swamps of the Gowanus area and developed the canal. His company built the four important 100 foot wide basins along the east side of the canal, between 4th and 8th streets.

Litchfield paid for the 4th Street slip that allowed Coignet to have 1,400 feet of wharf space, making possible the tons of raw materials to be delivered, and the finished product shipped out by barge. When Coignet closed in 1882, Litchfield’s Brooklyn Improvement Company took over the office building as their own. Goodridge kept an office there for a while, but then moved his operation on the Raritan River in New Jersey. He stayed interested in concrete for the rest of his life. His last paper, on laying concrete underground, was published in the year of his death, in 1900.

Litchfield’s Brooklyn Improvement Company sold off many of its holdings as the 19th century rolled into its final two decades. The land near the park went to residential development, some of the finest in Brooklyn. Long after Litchfield’s death in 1885, his company continued under the leadership of his heirs. During the 20th century, they began unloading the Gowanus properties, and the now defunct Coignet plant was torn down and replaced by other industries. But the office building remained, still company HQ for the BIC.

In 1957, the Brooklyn Improvement Company put the Coignet building up for sale. They no longer needed an office. Few people knew the significance of the building. In the 1960s, the structure was “brightened up” by brick facing the entire building in a bright red brick veneer, and coats of cement wash were slathered on the ornamental elements. It was used by several small companies until it was abandoned. As we known and have all seen, it deteriorated, and stood forgotten, until Whole Foods bought the entire site in 2005, and the building became the topic of conversation for the first time in years.

The Coignet building is tough. Gilmore, Goodridge and Field built one tough little concrete building. It’s lasted for a long time without any repairs or any love. Yet the elements remain on the façade, except where they’ve been removed. The building can be restored, without that awful brick, and made beautiful again. Let’s hope that indeed happens. It really is an important building, worthy of keeping around for another century or two. It was landmarked in 2006. GMAP

This article was written from research by Matt Postal for the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and expansion of this info can be found in the designation report for the Coignet Building, complete with more detailed photographs.

(Photograph above:1939 tax photo, Municipal Archives, via Landmarks Preservation Commission)

how do you pronounce coignet?

i am against most of the power-grab antics of the LPC but this does seem unique enough to protect

if they cared that much about this structure than why wasn’t it restored or fixed decades ago.

Just the thought of wanting to tear it down, now suddenly people are up in arms over that. Well, duh, you people did nothing to help it get restored…..why should this eye sore still stand and be left to rot for another decade…..

basically shyt or get off the pot…keep the building and fix it, or tear it down…but do something except whine about it, that is my job.

whatever.

***sticks tongue out****

The only source of “wah wah wah” here is you, dear Stargazer.

what I mean by “you people” is the people that say “oh, no, don’t tear it down”, wah wah wah…..its land marked…..or a “committie that says no, you can’t tear it down”, or a “groups that wants to preserve it”…….that’s what I meant. You know there is always someone that opposes soemthing…….

well it is pretty much an eyesore the way it is, would tearing it down really make that much of a difference? surely you understand what I mean?

Would it have been nice if the little structure was fully restored and occupied, and landscaped, of course…….but that doesn’t look like it is happening any time soon.